Whitehot Magazine

October 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

October 2025

As Fleeting as Dew and Lightning: Kexuan Zhao’s First Solo Exhibition

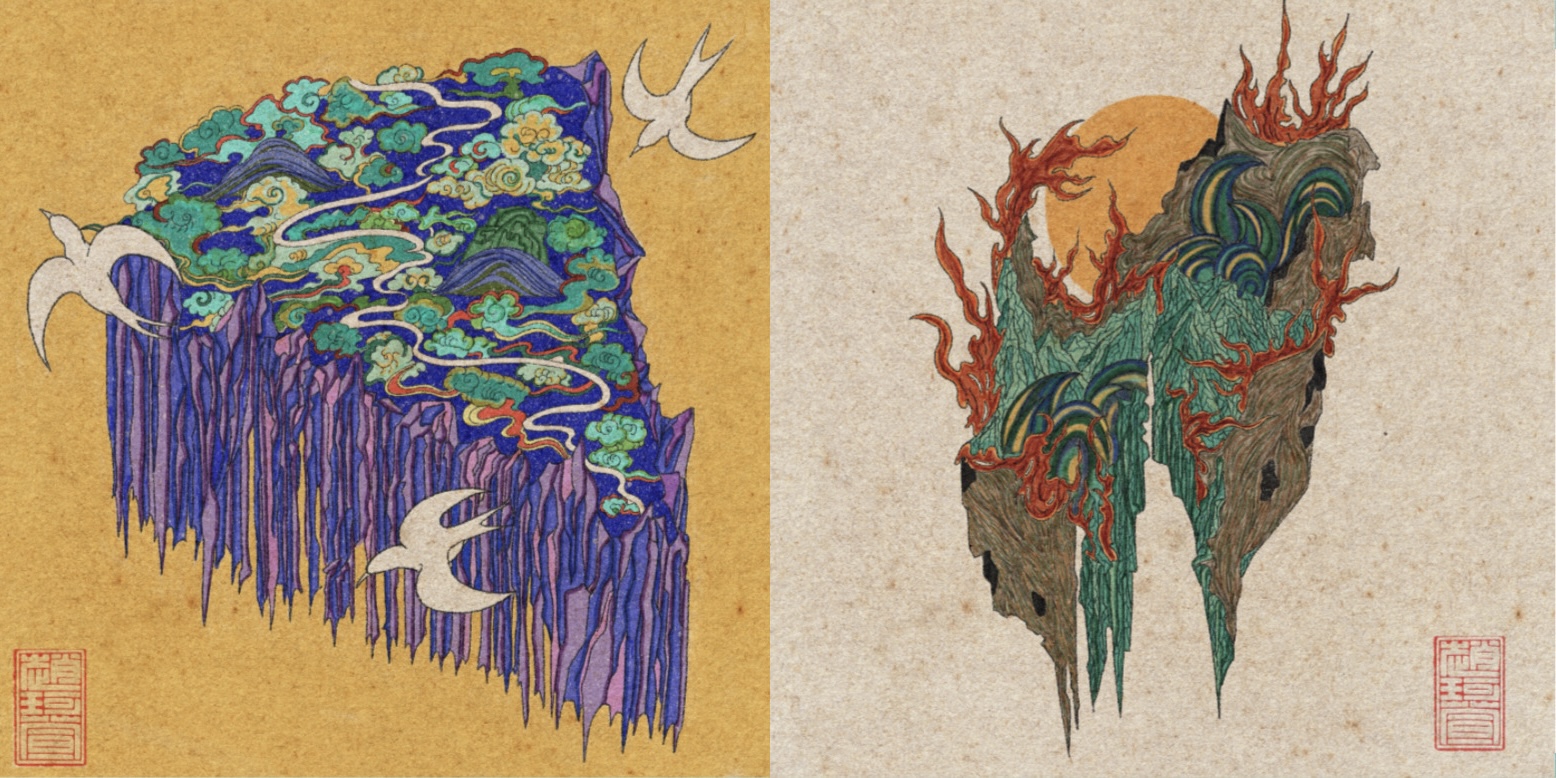

Kexuan Zhao The World in My Eye Sockets 878*472mm 2023

BY SERENA HANZHI WANG July 20, 2025

Illusions of being a Butterfly

I step into the Flowing Space Gallery and feel time slow to a hush. The title of the exhibition — As Fleeting as Dew and Lightning — hangs in my mind like an echo. In a Buddhist sutra, all worldly phenomena are compared to a dream, a flash of lightning, a drop of dew. Standing here, I recall dawns from my childhood when dew would cling to grass for an instant before evaporating in the first light. I recall summer storms where lightning revealed a landscape in one brilliant split-second, then left me blinking in afterglow. Kexuan Zhao’s paintings capture that same sense of impermanence. They invite me into moments that gleam and vanish, asking me to hold memory and change in the same breath.

Before stepping into individual works, it’s worth understanding the visual language Zhao paints in. Many of the pieces in As Fleeting as Dew and Lightning are rendered in Gu Cai (古彩), a traditional Chinese pigment technique that lies somewhere between watercolor and gouache. As Zhao explains, Gu Cai lacks the pure translucency of watercolor and the full opacity of gouache, giving her works a muted, atmospheric quality.

The first painting I encounter, Happiness is a Butterfly, glimmers with a quiet mystique but adds a bit of modern sensibility. In it, a huge moth-like butterfly hovers nearly connecting the crescent moon above with an invisible earth below. Its wings span a gulf of deep blue night. Only upon closer look do I notice a tiny caterpillar inching up the wrist of a translucent hand in the corner.

The image feels drawn from a half-remembered fable. Zhuangzi’s ancient dream: the philosopher who slept and became a butterfly, then woke up unsure if he was a man who dreamed he was a butterfly or a butterfly now dreaming he was a man.

Gazing at Happiness is a Butterfly, I feel an awareness that no state of joy or sorrow lasts forever. The moonlit butterfly might be “happiness” itself: beautiful and free but impossible to hold. The caterpillar reminds me that life marches on in cycles; endings carry the seed of new beginnings.

Kexuan’s work makes me wonder if modern people still care about the mythical — the spiritual frameworks that once shaped our lives. Despite our rational age, questions like where am I from? where am I going? persist. Zhao bravely leans into those questions, using painting as a vessel for longing, ritual, and the half-remembered truths we’re often too afraid to face.

Kexuan Zhao Happiness is a Butterfly Watercolor, Acrylic marker 16*21cm 2023

Just a few steps away, another work draws me in with a very different yet complementary vision. The World in My Eye Sockets is its title – an arresting phrase that makes me suddenly conscious of my own act of seeing. The painting centers on a human eye shedding crystalline tear. Along the path of the tear, minuscule ants are painted, climbing upward, drawn to the salt. This small, intimate detail startles me. I lean in close, almost holding my breath, to examine the tiny trail of ants venturing into the fluid of a human tear. I like this work.

In The World in My Eye Sockets, I sense the artist’s invitation to consider scale and inner experience. The tear magnifies private emotion – sorrow, relief, or perhaps awe – into something vast. Those ants, so small yet so purposeful, suggest that even the most personal grief or joy can attract forces from the outside world.

It’s as if our inner emotions send out signals that ripple beyond us. I’m reminded of every times I’ve cried and my cat would come to my side, or how a friend once told me that empathy is the true god of nature — that humans, animals, and even plants carry this power within them.

Zhao’s ants seek out the salt of tears, as though life itself is drawn to the wellspring of feeling. In the reflected light of the tear I also catch a hint of my own reflection – my eye looking at this painted eye. It’s a gentle mirror. I find myself remembering a moment years ago when I stood in the rain on the Manhattan High Line, tears mixing with raindrops, feeling utterly alone but also strangely connected to everything around me — the fancy Chelsea buildings, those strange little plants along the High Line, even the tourists who looked at me strangely — I felt them. This painting awakens that memory.

(picture seen on top of the page)

Breaking and Remaking

As I move further into the gallery, the themes of transformation and rebirth become even more pronounced. On one wall hangs a diptych titled Genesis of the Divide. Its two parts speak to each other like day and night. In the left panel (Part 1), I discern swirling forms and a sense of chaos, as if a world is churning in darkness before creation. On the right panel (Part 2), there’s an emergence of clearer shapes and a gentle light – a feeling of a world reconstituted anew. The reference to the Chinese creation myth of Pangu splitting the sky and earth is subtle: a suggestion of a giant figure or force cleaving one reality to forge another.

Yet Zhao’s interpretation of this “divide” is anything but violent. Unlike many creation stories that begin with explosive battles or dramatic ruptures, her Genesis of the Divide feels tender. There is a softness in the right-hand image especially, as if the new world after the great divide comes into being with a sigh of acceptance rather than a thunderclap. Shapes that might have been jagged in the first panel transform into gentler, flowing lines in the second. It occurs to me that Zhao is visualizing an internal awakening – the kind of profound change that happens inside one’s consciousness when illusions fall away.

Looking at this diptych, I reflect on how it mirrors experiences of personal transformation. Part 1 feels humorous—primordial chaos depicted in a Chicago deep dish pizza. But Part 2 is unexpectedly tender. It is not the harsh slashes of a big bang, but more like petals unfolding or a sunrise cresting. By contrast, Part 2 suggests what comes after that darkness: not a triumphant conquest, but a gentle rebuilding. Zhao seems to be saying that when we accept impermanence – when we truly grasp that life is as fleeting as dew on grass – a new order can naturally emerge from the chaos.

Her imagery implies; chaos gives birth to order, and order will eventually dissolve back into chaos, only to form again. It’s certainly about finding a roadmap for personal growth too: the breaking of the ego and the gentle re-ordering of the self in tune with the impermanence of all things. Zhao’s brush (or digital pen) becomes a storyteller here, and the story it tells is of the psyche’s capacity to heal and re-create itself. The Genesis of the Divide diptych leaves me with a quiet hope: that every shattering in life carries within it the making of a new whole, if we have the patience and openness to let it form.

Kexuan Zhao Genesis of the Divide Digital Art 237*237mm 2024

Collapse and Continuity

Turning the corner into the next room, I come face to face with a painting that crackles with tension. In Ever-changing and Unpredictable like Waves and Clouds, a dramatic confrontation is frozen in time: a black wolf lunges mid-air toward a white horse, jaws open, poised to tear into the horse’s neck. The horse rears back in terror. The wolf’s eyes – wide with a mix of rage and pain – and the horse’s posture: an animal instinctively recoiling.

I find myself holding my breath, judging, even, as I absorb this image. It’s like a scene from a mythic battle or a fable about the folly of war. Zhao’s title underscores the message: in war, in life, nothing is certain. The painting captures that razor’s edge when fortune flips. One moment the wolf seems victorious, the next it is struck down; the horse that was about to die is also lost to the arrow meant to save it. It’s a haunting, brutal paradox.

As I stand before this sudden violence, I’m reminded of how history often unfolds — full of unintended consequences. Minds drift, almost involuntarily, to stories we've heard from our grandparents — how a twist of fate during war spared one life and took another. Maybe it was a town bombed in the night, one neighbor surviving by going north, another lost by fleeing south. These memories are not distant, I can assure you; they live in us. Zhao’s painting reaffirms the sense that fate is arbitrary, and even the hunter can become the hunted in an instant.

Stepping away from the intensity of that scene, I find a quieter yet equally profound work nearby: Where Lies the Path to Home?. This painting has a different mood – one of aftermath and questioning.

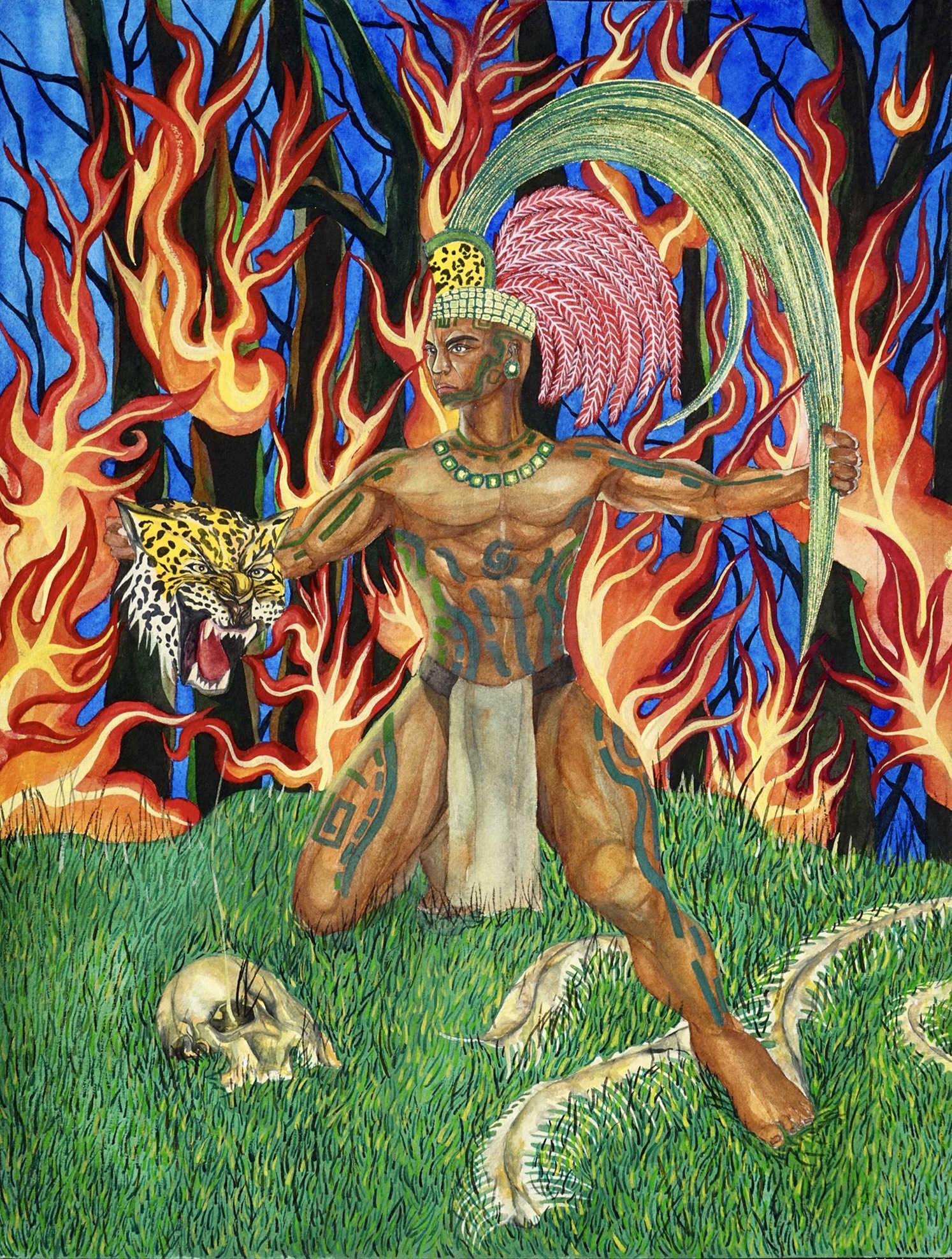

At its center stands a young man portrayed with Mayan features, holding a leopard’s head under one arm. Under his foot coils a snake, whose tail he steps on as if pinning down a dangerous force. Around him, I can make out hints of ruins, alluding to a fallen Mayan temple or a shattered village. The sky above is dim, with a twilight palette. He seems to be asking silently: How do we go on after everything falls apart? How do we rebuild vitality after the collapse of a once-perfect world? How do we face the possibility of change when it comes as destructive upheaval? Where Lies the Path to Home? and the wolf-and-horse battle scene together form call-and-response.

The war scene shows how a world can shatter in an instant; the Mayan scene asks how one learns to live again in the shards of what remains. Between them, I feel the full weight of loss and the fragile bud of renewal. My thoughts wander to current times — stories of refugees rebuilding their lives after wars, or global communities coming together after natural disasters. The mythic imagery might be ancient, but the emotional truth is contemporary and personal.

Kexuan Zhao Ever-changing and Unpredictable like Waves and Clouds Watercolor 31*41cm 2024

Kexuan Zhao Where Lies the Path to Home? Watercolor, Mineral Pigment 31*41 2024

Beyond Life and Death

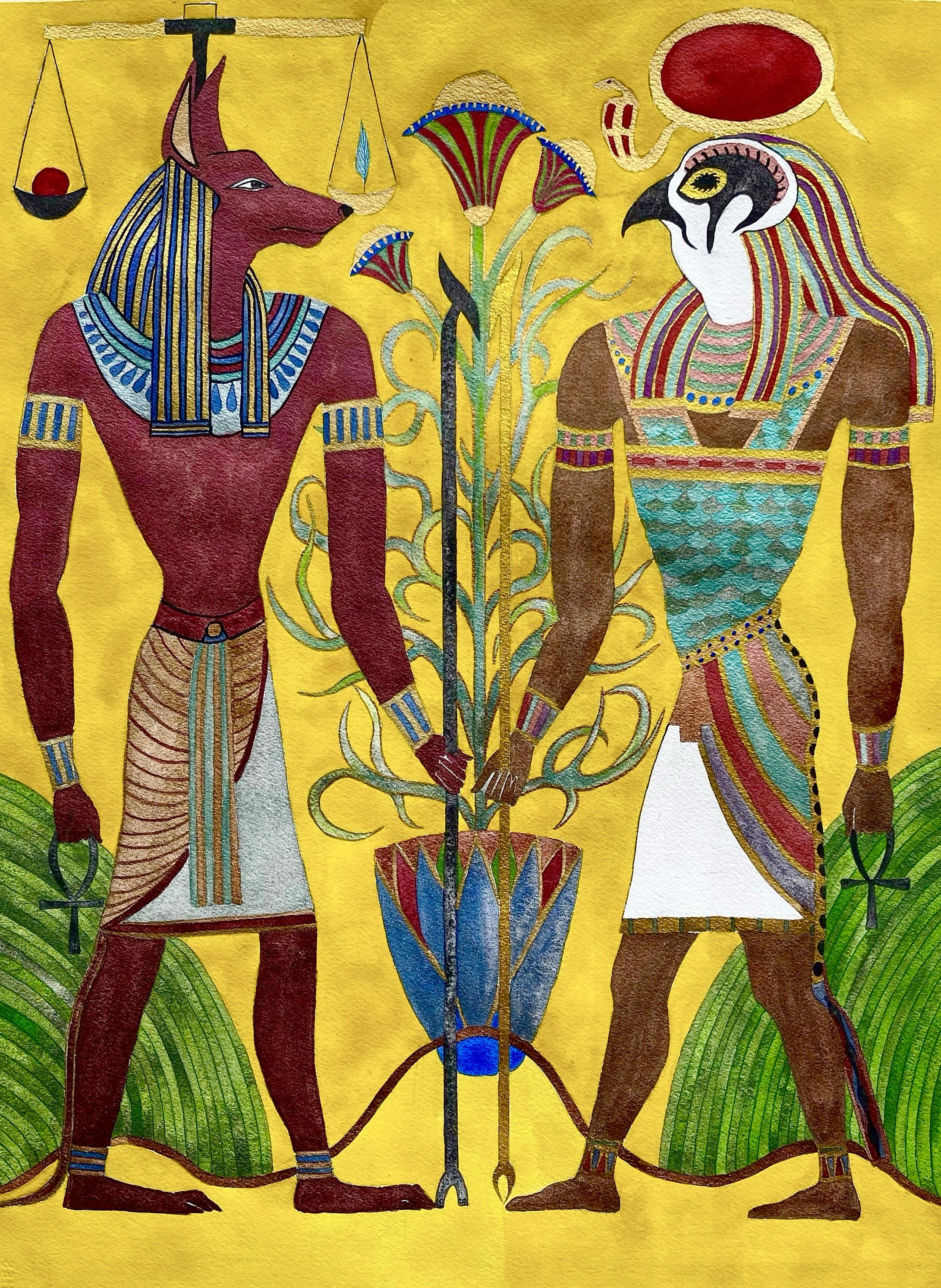

Near the end of my walk through the exhibition, I encounter Life Now and Beyond, where Horus and Anubis — sky god and death guide — face each other like mirrored forces. After the ruptures of war and collapse, this painting feels like a quiet reckoning with continuity. Life and death are no longer opposites, but companions in a cycle beyond logic or time.

Zhao’s rendering is delicate yet profound: gold meets shadow, the living meet the beyond. In their calm postures, I see an ancient dialogue still alive — a reflection of the same questions we carry today: What comes after? What endures? Her brush quiets their grandeur—not to diminish it, but to render it almost childlike, as if the myth lives inside us still.

It occurs to me that throughout this exhibition, there’s been a thread of pairing and echoing: the micro and macro in the tear painting, the man and butterfly, the two panels of the Genesis diptych, the wolf and horse, and now Horus and Anubis. Dualities abound. Maybe art is a kind of conversation with oneself — meaning is definitely not found in one absolute, but in the space between forces: the divide and the connection. This feels like a distinctly Gu Cai sensibility as well — the medium itself lives between watercolor and gouache, between transparency and opacity, blending and balancing.

My journey through the gallery ends with a final Buddhist painting. Its title strikes me as both confrontational and slightly TMI: The Compassionate Bodhisattva, Why Don’t You Open Your Eyes and Look at Me?. In this piece, Zhao introduces the image of a Bodhisattva — a being of great compassion in Buddhist teaching — but with an unexpected twist. The Bodhisattva is depicted with closed eyes, while in front of it (presumably a self-representation) stands an “ambivalent atheist,” as the catalog describes.

I stand there for a long time, feeling the weight of that title question hanging in the air. Why don’t you open your eyes and look at me? It is a direct appeal, almost a prayer, from someone who doesn’t fully believe in prayer. The “ambivalent atheist”? Is Zhao speaking to those who consider religion a beautiful symbol, yet, in moments of crisis, find themselves whispering a plea to a higher power they’re not even sure is listening.

I feel a lump in my throat as I think about the times I’ve done the very same — when life’s troubles drove me, despite my skepticism, to ask for help from something, someone, out there.

Kexuan Zhao Life Now and Beyond 48*36cm 2025

Kexuan Zhao The Compassionate Bodhisattva, Why don’t You Open Your Eyes and Look at Me? Watercolor, Mineral Pigment 31*41cm 2024

As I prepare to leave the exhibition, I notice how the luminosity of the Gu Cai medium in this final piece creates a kind of halo around the Bodhisattva. It’s as if the air itself in the painting is imbued with mercy. In a show so much about inner change, impermanence, and finding order after chaos, this last painting addresses the desire for guidance and understanding. It speaks to that part of us that, after witnessing war and loss, after rebuilding and transforming, still yearns for a compassionate gaze to affirm that our struggles are seen.

I step back and take in a final view at Zhao’s exhibition. The Flowing Space Gallery feels different now than it did during all my previous visits. It’s as though each painting has marked a step on a journey through not just Zhao’s memories and myths, but my own. Yet as I reflect on this impulse — to equate art with dew and lightning — I begin to question whether her illustrative approach risks flattening the vast emotional and mythological weight she intends to convey.

Walking out into the late afternoon light of the city, I carry those traces tenderly, aware that I have witnessed something both ephemeral and unforgettable.

Kexuan Zhao (b. 2000, Zhejiang, China) is an artist currently living and working between New York City and Shanghai. She holds an M.A. from Columbia University (2022–2024) and a B.F.A. from Parsons School of Design (2018–2022). Her solo exhibition As Fleeting as Dew and Lightning was presented at Flowing Space Gallery, New York from June 26 to July 7, 2025. Zhao’s work has been featured in numerous group exhibitions, including the September Primer Exhibition (2023, 2022) and the Salon Pin-up Exhibition (2023) at Macy Art Gallery and iidrr Gallery in New York; Le Radici dell’Arte at Thames Art Center x Freezingfog (2022); Manifesto Fashion Show at 800 Show in Shanghai (2019); and Distanceless Society and Dancing Inspiration at Stefano Boeri Architetti and New Gallery of Art in Shanghai (2018).

Image courtesy of Kexuan Zhao. All rights reserved.

Serena Hanzhi Wang

Serena Hanzhi Wang (b. 2000) is an award-winning art proposal writer, multimedia artist, and curator based in New York City. Her work spans essays, exhibitions, and installation Art—often orbiting themes of desire and technological subjectivity. She studied at the School of Visual Arts’ Visual & Critical Studies Department under the mentorship of philosophers and art historians. Her work has appeared in Whitehot Magazine, Cultbytes, SICKY Mag, Aint–Bad, Artron, Art.China, Millennium Film Workshop, Accent Sisters, MAFF.tv, and others.

view all articles from this author