Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

Endless Limits: The Work of James Howell, 1962–2014

James Howell. [L-R] Seven Studies, c. 1984. Acrylic and graphite on paper. 13 ¾ x 11 in. each. Untitled Nine Part, 1987. Acrylic on linen. 72 x 72 in. overall. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

James Howell. [L-R] Seven Studies, c. 1984. Acrylic and graphite on paper. 13 ¾ x 11 in. each. Untitled Nine Part, 1987. Acrylic on linen. 72 x 72 in. overall. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

BY CLARE GEMIMA December 4th, 2025

Endless Limits: The Work of James Howell, 1962–2014

September 13, 2025–February 8, 2026

279 Montauk Highway

Water Mill, NY 11976

Co-organized by Kaitlin Halloran, Associate Curator and Publications Manager, and Scout Hutchinson, The FLAG Art Foundation Associate Curator of Contemporary Art, Endless Limits marks the first comprehensive retrospective of American artist James Howell (1935–2014) which will run through February 8, 2026 at the Parrish Art Museum. Best known for his meditative, chromatic, and spectral explorations, Howell produced hundreds of paintings, drawings, and prints over the course of decades that distilled experience into hue. With a hyper-fixation on the seemingly infinite range of gray, seen acutely in works like Series 10, 1996–2014, the exhibition places Howell’s monumental late paintings in dialogue with his lesser-known earlier works, and traces his long investigation into balance and restraint from the very beginning. For him, limitation gradually became a form of liberation. “You think you might be trapped by setting limits,” he once said, “but I found out a long time ago that everything is in everything.”

James Howell. [L-R] Standing Figure, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Untitled, 1965. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Figure Reading, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Untitled, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 24 x 27 in. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

James Howell. [L-R] Standing Figure, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Untitled, 1965. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Figure Reading, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 45 x 51 in. Untitled, 1969. Acrylic on canvas. 24 x 27 in. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

The first gallery introduces Howell’s seldom-seen pigmented, figurative canvases that span the mid-60s to early 70s, a formative period that contrasts sharply with his much later monochromes. Depictions of his wife Sandra and young daughter Karen root Howell within a world of domestic intimacy and painterly observation reminiscent of art critic and painter Fairfield Porter (1907-1975). The two met in East Hampton shortly after the death of Howell’s father, and their friendship—sustained through visits, phone calls, and letters until Porter’s passing—proved deeply influential. Becoming both a mentor and interlocutor to Howell, Porter encouraged the artist to trust the sincerity of what surrounded him. This influence is visible in Figure Reading, Girl in Landscape, and Standing Figure (all 1969) through Howell’s lush handling of light, the warmth of his palette, and the quiet familiarity of interior and familial scenes.

Born in Kansas City, he studied architecture and English literature at Stanford, where the Pacific’s earth-toned palette greatly shaped his vision. Later, in New York and finally in Montauk specifically, Howell turned to the natural world to study its mutable colors as metaphors for variation. Regardless of not having a traditional arts education, he approached painting with intellectual rigor, a remarkable adaptability, and an intense technical curiosity. Whilst residing on the West Coast, he absorbed the color harmonies of painters like Richard Diebenkorn (1922-1993), and by the late 1960s, during a pivotal residency at the Art Students League in Woodstock, New York, he began studying with Richard Mayhew (1924-2024) and Walter Plate (1925-1972). This period marked Howell's transition from figuration to abstraction, where canvases begin to saturate with bands of color and first hints of his signature restraint become apparent. The Place and Boxcar series, 1960-69, that recall Rauschenberg and Johns, flirt in this pivot.

James Howell. Port Blakely Series Wicker, 1976. Acrylic on canvas. 62 x 46 in. Photo courtesy of the James Howell Foundation

James Howell. Port Blakely Series Wicker, 1976. Acrylic on canvas. 62 x 46 in. Photo courtesy of the James Howell Foundation

By the mid-1970s, Howell’s figures had fully dissolved and been replaced by pared-back palettes, drifting fields, and atmospheric whirlpools, seen especially in his Port Blakely series, 1976–1980. “When I recognized color as a unidimensional aspect of painting,” he wrote, “the margins between the forms fell open. They were no longer lines at all, but narrow masses of chromatic gradation.”

In Port Blakely Series Wicker, 1976, thick and gestural layers of paint – golden, apricot, and sunlit-ochre colored strokes— disguise its brooding, blood-red undercoat. However subtle in Howell’s move towards abstraction, the painting retains a residue of the figure, even just with its fleshy pigments. Living on Bainbridge Island, Howell gradually thinned his vivid hues into a more contemplative range, and near-monochromes that would define his later work. Around this time he was also reflecting upon the skies he saw as an avid pilot (according to his flight-log he flew from 1953-7) which undeniably altered his perspective. Adjacent to Diebenkorn’s aerial approach, Howell’s POV paintings depict the clouds, vast veils of light, and misty storms he may have encountered in flight. A faint, X-ray–esque color scheme in Port Blakely #23, 1977, hints at suggestions of a spine or ribcage—the figure is again detectable, though merely at a stretch. Yet both Untitled IV, 1980, and Sand I, 1981, demonstrate a continuation of Howell’s drift further away from the body, where orbs blur in and out of focal range and float effortlessly within the picture plane, as if spheres suspended in atmos.

In Nine Part Piece, 1987, Howell’s meditative balance unfolds across three rows of three linen panels. Forming a tessellated constellation inspired by the measured harmony of Chinese divination, three circular concentrations of light radiate against a deep midnight blue in each composition. Through its subdued palette and softened edges, the painting exudes a quiet conviction. As his spiritual discipline deepened and his process grew increasingly methodical, Howell's scope—both in poise and production—expanded into something thrillingly unknown, perhaps even limitless. This piece marked the beginning of a long journey towards what he would one day call the “perfect gray.”

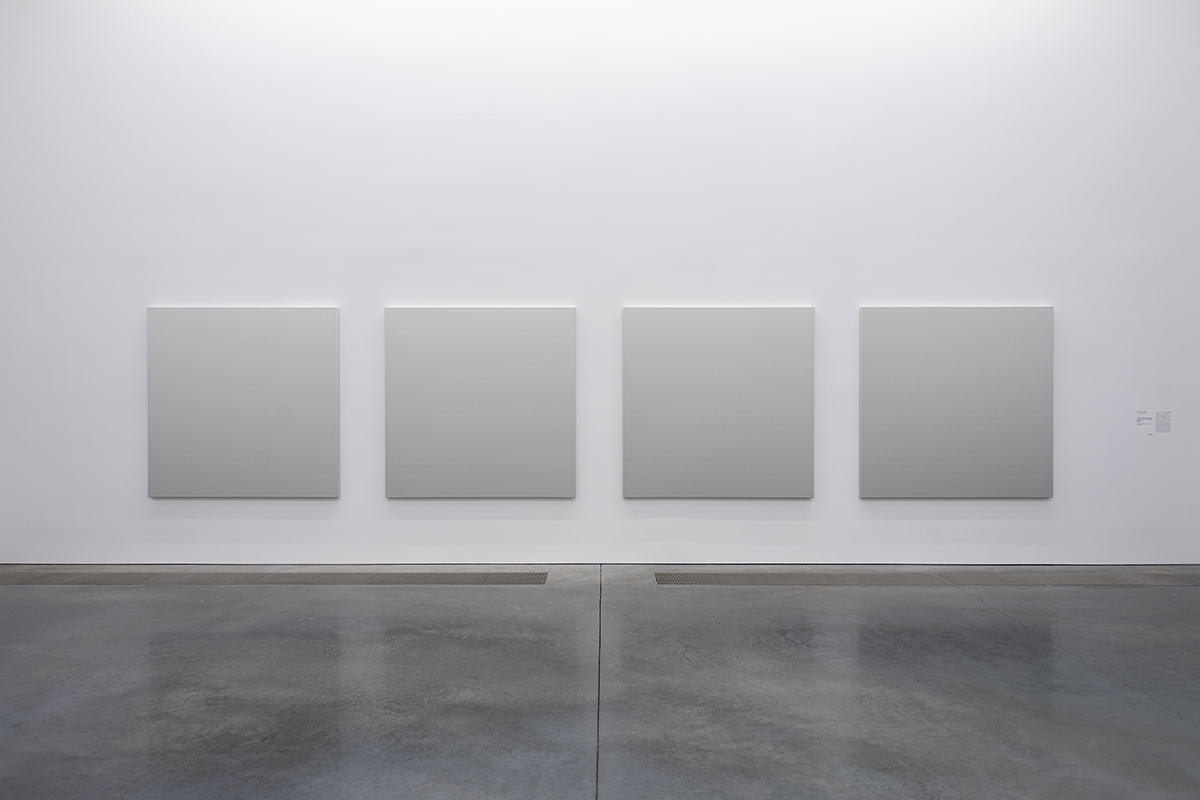

James Howell. 94.75-96.66 Four - part progression 10/19/03, 2003. Acrylic on canvas. 66 x 66 in. each. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

James Howell. 94.75-96.66 Four - part progression 10/19/03, 2003. Acrylic on canvas. 66 x 66 in. each. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum, Photo credit: Gary Mamay

The installation of Series 10, at both the James Howell Foundation and the Parrish Art Museum, is tuned to the logic of light itself. Along the gallery’s south wall, in the exhibition’s Where Extremes Do Not Hold section, a four-part progression made in 2003 shifts horizontally through a spectrum of grays—iron, manatee, dusty, silver, gallery, ghost, seashell—each mixed from just three pigments: titanium white, ivory black, and raw umber. The bands surface only as the viewer draws close. These environments—co-constructed with his partner Joy, a master printer who mixed pigments and sustained the controlled conditions he relied upon—proved essential to the series’ evolution and longevity, culminating in Howell’s discovery of more than 12,000 distinct shades of gray before his passing. Acrylics on canvas, inks and graphites on paper, aquatints, and digital prints featured in Series 10 mark the apex of Howell’s obsessive devotion.

In the adjacent gallery, an uncanny resonance emerges with Hiroshi Sugimoto’s (b. 1948) Time Exposed portfolio, a showcase of fifty photolithographs printed in 1991 that capture ocean-scapes that span the Caribbean, Atlantic Ocean, and the English Channel. Each cinematic image, created between 1980-91, pursues what the artist describes as a “perfect moment” unbroken by time. Joy recalled that Howell admired Sugimoto deeply, and once described his own paintings as “a Sugimoto on a cloudy day without a horizon line.”

The works in dialogue present a conceptual circuit neither artist may have been conscious of, however, the relationship between Howell’s boundless gradations and Sugimoto’s distilled equilibriums of sea and sky feel intimately connected, legible, and aesthetically intuitive. Shaped by Howell’s genuine admiration for the work of Sugimoto, the pairing reveals both artist’s parallel fixations on the elusive search for an image so precise that it embodies a surreal timelessness. As one artist loses himself in seeing, the other is lost at sea.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Irish Sea, Isle of Man, 2008. Photolithograph. 9 ½ x 12 in.© Hiroshi Sugimoto. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum.

Hiroshi Sugimoto. Irish Sea, Isle of Man, 2008. Photolithograph. 9 ½ x 12 in.© Hiroshi Sugimoto. Photo courtesy of Parrish Art Museum.

From figuration to fog, pigment to particle, pieces in Endless Limits invite viewers to look into and beyond what the artist spent his whole life charting. Scrutinizing his pursuit of gray, the exhibition expertly clarifies that his overall process was not a retreat from color, but a sustained inquiry into perception itself. With a practice defined by attention, patience, and a willingness to follow variation into its most subtle registers, James Howell’s slow revelation of tone—where striking simplicity meets radical depth—opened onto inexhaustible, profound possibilities, and offered an experience nothing short of enchanting.

Clare Gemima

view all articles from this author