Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

The Art World's Misunderstood Beauty: 'William Tillyer: The Watering Place’, Bernard Jacobson Gallery

Installation view of William Tillyer: The Watering Place, October 2025. © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

Installation view of William Tillyer: The Watering Place, October 2025. © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

By GRACE PALMER January 19, 2026

Since penning an open letter to the art community in 2022, Bernard Jacobson has been a passionate advocate for the recognition of William Tillyer as one of Britain’s “great modern artists”. This continued, and deeply personal advocacy for Tillyer is no more apparent than with Jacobson’s most recent exhibition (ending January 23rd), 'The Watering Place'. Intimate, yet eruptive in colour, expression and innovation, Tillyer commands the gallery space. This exhibition, both pastoral and enriched by modern sensibilities, masterfully abstracts the landscape genre. Watercolours, such as The Watering Place V and Landscape with Bridge, linger over their subjects, losing themselves within nature’s ripples and pulses; emblematic of the filmic ennui of modernist masters like Fellini and Antonioni. I had the privilege of speaking with Bernard Jacobson about his enduring admiration for Tillyer, their longstanding friendship and the often misunderstood beauty within these paragons.

Spanning nearly five decades, the relationship between Tillyer and Jacobson has flourished in concordance with their respective careers. Reflecting on their first encounter, Jacobson recalled their initial collaboration as a “terrific moment” that captivated London’s art world. Selling out these early prints to the V&A, the Arts Council, the Tate and even Ron Kitaj, Jacobson knew he had discovered a tour de force of modernist expression. It is from this pivotal moment that their friendship (and Tillyer’s portfolio) “grew and grew”. What first excited Jacobson, and continues to do so, is Tillyer’s “awkward contemplation”. His approach does not strive for exact representations. Rather, Tillyer presents the seascape which is not a seascape, the flamenco as only her motions, and the land as a geometrical puzzle waiting to be solved. For Jacobson, it is his “masterful use of material” that exemplifies the innovative and experimental spirit of William Tillyer. In works like The Lumsden’s Pool and Oak Leaf and Bridge, lattice structures appear as recurring motifs. Understandably, these structural patterns reference his particular use of acrylic mesh in place of the stretched canvas. By pushing paint through these suspended sheets, he allows the medium to drip, splash and accumulate into quasi-relief forms. Yet, there is also something inherently oxymoronic I find in Tillyer’s drive towards the lattice. Systems so detailed, structured and secure – his building blocks – signify Tillyer’s refusal to partake in the medieval nature of the canvas, his embrace of illusion and dismissal of the frame. This confrontation with artistic logic, as poet John Yau puts it, makes Tillyer the most “adventuresome artist of our time.”

William Tillyer, The Watering Place V, (2013) acrylic on mesh and canvas, 177.8 x 203.2cm (70 x 80ins). © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

William Tillyer, The Watering Place V, (2013) acrylic on mesh and canvas, 177.8 x 203.2cm (70 x 80ins). © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

Plastic mesh sheets and an active engagement with material indicate a bedrock of machinery, conceptualism and sleek monochromasy. As a child of the ‘60s, Tillyer would have been immersed in a Bauhaus syllabus, the cool edge of the Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night and the intellectualism of Tom Stoppard and Richard Hamilton. Aided by the time inevitably spent in his father’s hardware store, it is hard not to see traces of Rauschenberg, Judd and Oldenberg in Tillyer’s materiality. And yet, his desire to “get out of the town, into the countryside” is what sets Tillyer apart from these high culture icons. In The Watering Place Study – Landscape with Bridge, the land is not the focal point. Rather, these natural aspects become structural hinges for his abstraction: the ideas of a bridge as geometry, a push-pull mechanism. It is here where the “pastoral meets industrial”, where the zeitgeist meets the genuine, where, in William Blake’s words, “men and mountain meet.” Tillyer may have maintained the stoic, retiring attitudes of his ‘60s upbringing, but his works speak to a bold traversing of the natural and man-made, a semi-bohemianism in collaboration with conceptualism, a bourgeois articulateness that exists only through his art.

“Infinity has a tendency to fill the mind with that sort of delightful horror, which is the most genuine effect, and the truest test of the sublime.” Edmund Burke’s principles of the sublime echo throughout art history’s engagement with the pastoral. It is in the works of Constable, Gainsborough, and Rubens that we find the most tangible and effective presentation of this “delightful horror”. For Jacobson, he is hard-pressed to name any British artist who has surpassed the infinite reverie of these canonical masters – bar that of William Tillyer. ‘The Watering Place’ is both an ode to the legacy of the landscape genre and an offering of an abstracted potential. Throughout the exhibition, one cannot help but notice the silent conversations happening between Tillyer and these legacy artists. His intimate studies for The Watering Place series hark back to the quiet contemplation in works like Constable’s The White Horse (1819) – these broad brush strokes, and reverence for the water’s edge palpable in each artist's vistas. Yet, as Robert Frost so eloquently articulates, when “two roads diverged in a wood, I took the one less travelled.” William Tillyer has endeavoured down that road and emerged as an artist far beyond his peers. In works like The Watering Place Study – Bridge, his watercolour is offered agency, free to blend, diffuse and move across the paper. As much as these painterly techniques call upon, and abstract, those of landscape’s virtuosos, I cannot help but experience the watercolour’s dissolution as reminiscent of the Yorkshire Moors’ temperamental weather conditions – a place untethered from fixity.

Installation view of William Tillyer: The Watering Place, October 2025. © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

Installation view of William Tillyer: The Watering Place, October 2025. © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

Growing up in Middlesbrough, Tillyer’s work expresses his continued “love affair” with the Yorkshire Moors. Like any good Modernist painter, Tillyer devotes his time to resting in, driving through and soaking up the visual sensations of his rural surroundings – even though he never paints en plein air. Such admiration for the land sparks anecdotes of Paul Nash leaping out of his car to excitedly photograph the view before him. An inherent paradox exists within Tillyer’s watercolours; this hurried urgency to capture the genius loci is only achieved through years of cogitation and immersion in the land. This is most evident through Tillyer’s consistent re-engagement with his work. As the landscape itself changes and develops over time, these paintings are afforded the same topographical shifts – building a history of marks that allow viewers to swim in a “watercolour world.” In 2017, Tillyer worked alongside British poet Alice Oswald to create complementary pieces reflecting on the powerful effects of water. Perhaps her words underscore the tension inherent within Tillyer’s work: “be amazed by that colour it is the mind’s inmost madness // but the sea itself has no character just this horrible thirst.” The sublime, in its “delightful horror” and “inmost madness”, is not merely concerned with beauty but an embrace of chance and accident, of change and acceptance. Tillyer engages with the temperamental in a way that the landscape painters of the past had yet to achieve. But, within this exhibition, Tillyer, Constable, Gainsborough and Rubens all sit by the watering place, beneath the “slow tree of influence spreading its branches.”

Richard Cook is credited with stating that categorising William Tillyer has been a difficult task for many art historians. For Jacobson, the “difficulty to at times read his work” and his “elusiveness” are both distinct limitations, but also the things that make his work so beautiful. Canonisation and the legacy of “the history of art” (as E.H. Gombrich would determine it) is now, more than ever, in a constant state of flux and re-evaluation. Jacobson’s enduring interest in bringing Tillyer into the canon is not one of blind devotion, but an understanding that he is “the best artist we have.” In his eyes, Tillyer’s best work will emerge in his 80s and 90s, unlike the shooting stars of Hockney. He is an artist who is “still producing. He hasn’t stopped producing, and what he’s currently producing is as good, if not better.” With these current revisions into our art historical legacies, perhaps it is high time that we too recognise William Tillyer as one of the “great modern artists.”

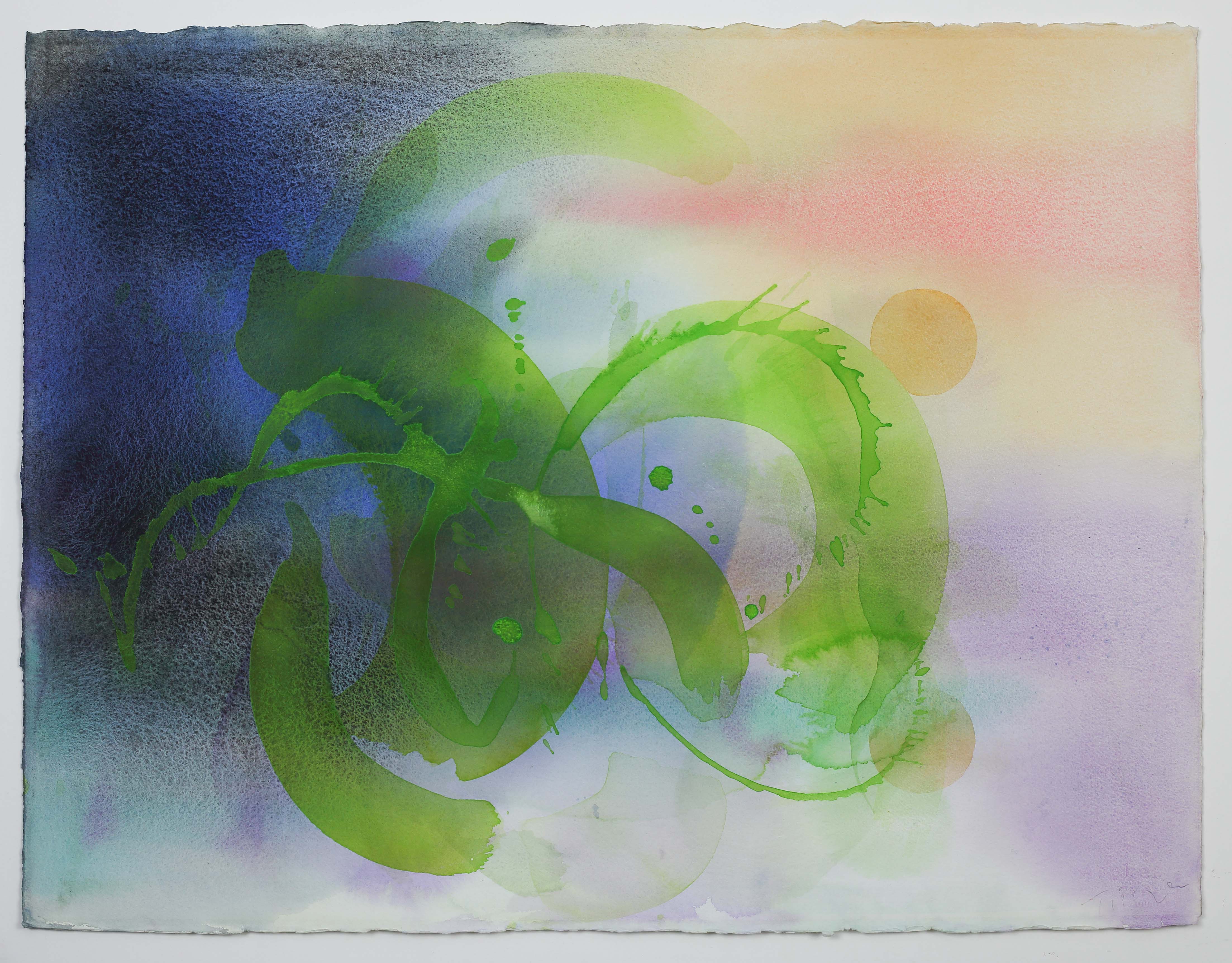

William Tillyer, The Watering Place, (2013) watercolour on Arches paper, 57.2 x 76.8cm (22 ½ x 30 ¼ ins). © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

William Tillyer, The Watering Place, (2013) watercolour on Arches paper, 57.2 x 76.8cm (22 ½ x 30 ¼ ins). © Bernard Jacobson Gallery.

My thanks go to Bernard Jacobson for taking the time to speak about William Tillyer, and to Lauren Glogoff of Bernard Jacobson Gallery for facilitating this meeting.

‘William Tillyer: The Watering Place’ runs between October 9, 2025 – January 23, 2026, at Bernard Jacobson Gallery, London. WM

Grace Palmer

Grace Palmer, an art historian and writer, specializes in the history of contemporary art and 1960s New York performance art. She contributes to Whitehot Magazine and is currently located in London, England.

view all articles from this author