Whitehot Magazine

December 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

December 2025

The Irrepressible Past: Lucas Cranach The Elder’s Venus Resurrected In Takako Yamaguchi’s Neo Traditional Art by Donald Kuspit

Installation view, TAKAKO YAMAGUCHI: INNOCENT BYSTANDER, Courtesy of Ortuzar Gallery, New York, NY

Installation view, TAKAKO YAMAGUCHI: INNOCENT BYSTANDER, Courtesy of Ortuzar Gallery, New York, NY

By DONALD KUSPIT April 25, 2025

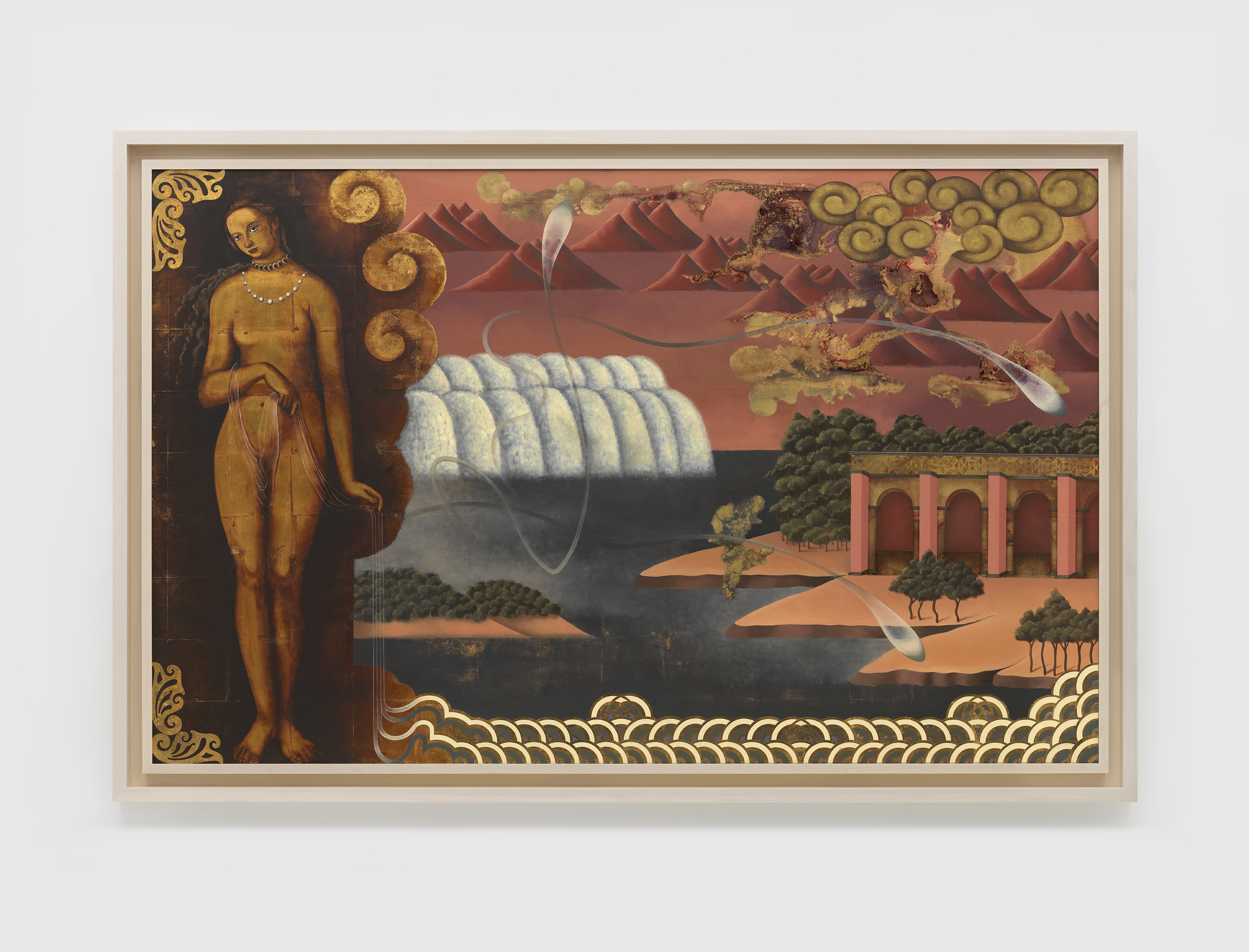

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past,” William Faulkner famously said—it’s just been suppressed by the present, ignored as though it never happened, or mocked as though it was a tired cliché, but a living artist can find subtle beauty and inspiration in Old Master museum art—the subtle beauty of Lucas Cranach The Elder’s Venus, the majestic nude that presides over the scene in Takako Yamaguchi’s paintings. Standing to its left side, she presides over its bizarre spread with visionary intensity, indicating that Yamaguchi is a kind of fantasist. She wants to “revive the ghost of a lost style in the form of something vain and pretty,” she says, but however vain and pretty Cranach’s Venus is—her body is manneristically elongated, eternally thin as though suffering from incurable anorexia, small breasted as though an immature adolescent (a sort of Twiggy), altogether unlike the full-bodied Venus of antiquity—she remains a powerful goddess. Her autonomy is not compromised by the presence of Mars or Adonis—any male lover, immortal or mortal. Cranach’s Venus is a radical, original vision of Goethe’s “eternal feminine that draws us on,” all the more so because she is eternally young.

Takako Yamaguchi, Innocent Bystander #8, 1988, Oil and bronze leaf on paper, 72 x 96 inches (182.9 x 243.8 cm), Courtesy of Ortuzar Gallery, New York, NY

Takako Yamaguchi, Innocent Bystander #8, 1988, Oil and bronze leaf on paper, 72 x 96 inches (182.9 x 243.8 cm), Courtesy of Ortuzar Gallery, New York, NY

I think Cranach’s lovely and lovable stand-alone adolescent Venus is a symbol of Yamaguchi’s radical autonomy: tired of and bored by “such mainstream positions in contemporary art as ‘the tough,’ ‘the ugly,’ ‘the angry’—sounds like a Clint Eastwood movie—she says she “sought inspiration in what a poet once dubbed ‘the trash heap’ of abandoned ideals”—“sentimentality, empathy, pleasure” along with “decoration, fashion, beauty.” All are antipathy to avant-garde art since Picasso’s misogynist Demoiselles d’Avignon, 1906, the touchstone of all its tough, ugly, angry, destructive, hate-filled renderings of woman’s body. They climax in Duchamp’s hate-filled Etant donnes, 1966 with its naked, raped, murdered woman, her face hidden, her vagina in the viewer’s face, and de Kooning’s vicious, violent rendering of woman’s body, turning it into a crippled, grotesque monster, as in the sculpture Seated Woman On A Bench, 1972/1976, in the name of “abstraction,” that is pure art (presumably). Speak of misogyny! More pointedly, all bespeak what the psychoanalyst Wolfgang Lederer calls the (not so unconscious) Fear of Woman, resulting in panic or anxiety in response to her, and with that defensive violation—in effect murderous rape--of her body. It is what Max Ernst’s La Femme 100 Tetes, 1929 and Picasso’s Minotauromachy, 1935 are about: they quintessentialize the anxious, violative treatment of women in modernist art

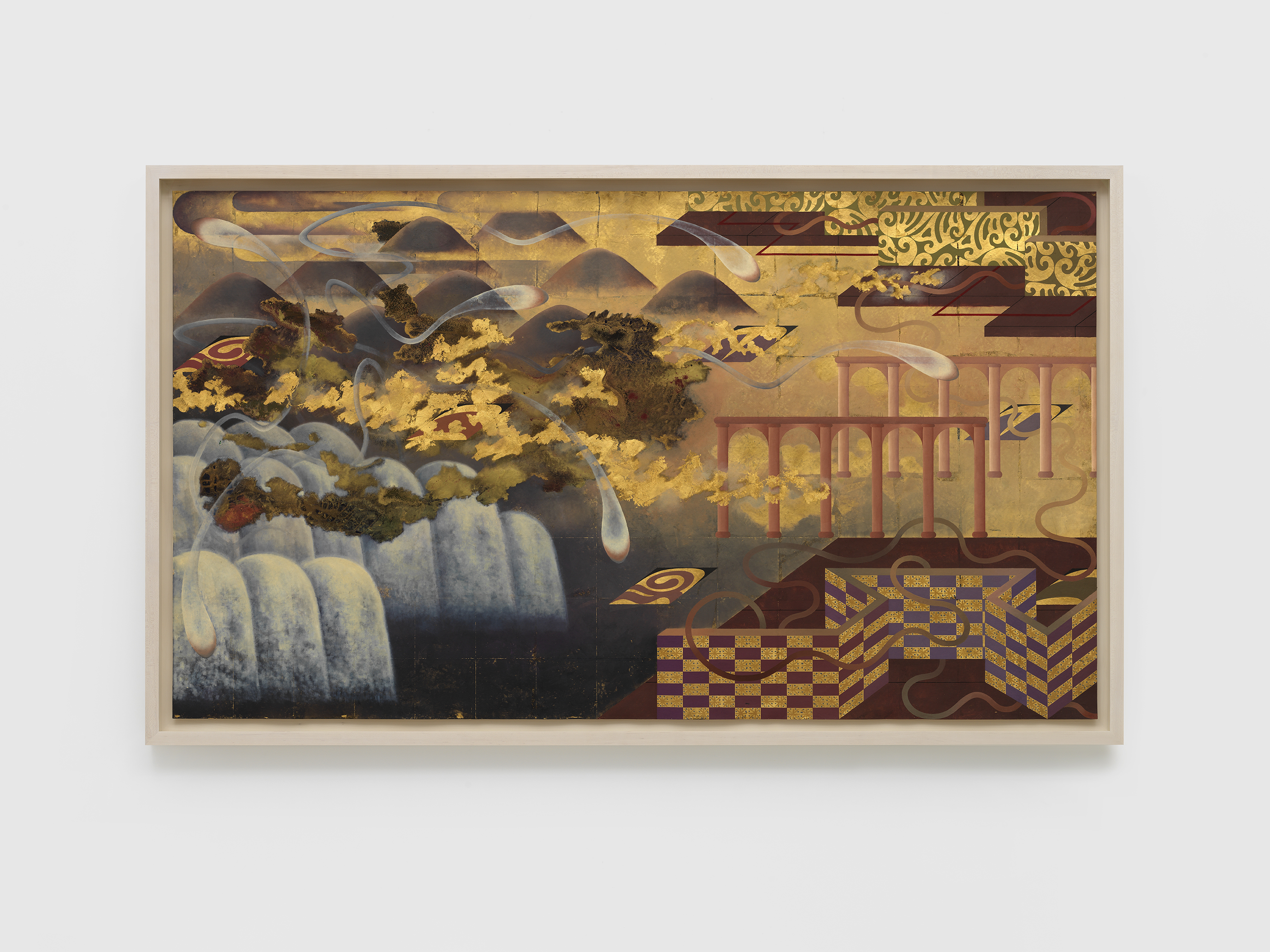

Innocent Bystander #4, 1988 Oil and bronze leaf on paper 53 x 83 1/2 inches (134.6 x 212.1 cm)

Innocent Bystander #4, 1988 Oil and bronze leaf on paper 53 x 83 1/2 inches (134.6 x 212.1 cm)

Yamaguchi’s return to tradition—her rendering of Lucas Cranach The Elder’s Venus (radically original for its time in view of its mannerist rejection of Italian Renaissance classicism)—is a radically creative rejection of modernism and postmodernism, perhaps above all their nihilistic treatment of women. The violence Duchamp, Picasso, Ernst, and de Kooning, among many other male “advanced” artists, do to woman’s soulful body—as though to enviously discredit and undo its traditional idealization, which is a celebration of woman’s natural creativity--is psychologically discredited by Yamaguchi’s resurrection of Cranach’s Venus, a fresh young woman, upright and lovely, as all the goddesses are in Cranach’s Judgement of Paris, 1528. In Cranach’s The Fountain of Youth, 1546 old women enter the fountain of youth and come out young, implicitly eternally young, like the goddess Venus. They have been in effect reborn—and immortalized, that is, become virginal goddesses—no old men are allowed in the Fountain of Youth. The men will die, the women are immortal—they have become goddesses—adolescent girls in the prime of youth--virginal goddesses. Celebrating Cranach’s Venus, her oddly immature, “unripe” body—in contrast, say, to Titian’s Venus With A Mirror, ca. 1555—confirming that she is eternally young, and as such a goddess, Yamaguchi restores wholeness and wholesomeness—integrity and autonomy--to woman’s body, repudiating its sadistic destruction in avant-garde art. Her Cranach Venus paintings are a radical feminist statement, for they show that woman has no need of man, and stands upright rather than reclining in bed, like Titian’s Venus of Urbino, 1538 or Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus, 1647-1651, looking at herself in a mirror and waiting for her lover, presumably Mars. Yamaguchi’s identification with Cranach’s autonomous Venus announces and confirms her feminism.

Le Temps Mêle #6, 1984, Oil and bronze leaf on paper, 48 x 83 inches (121.9 x 210.8 cm)

Le Temps Mêle #6, 1984, Oil and bronze leaf on paper, 48 x 83 inches (121.9 x 210.8 cm)

Yamaguchi may be traditionalist, but her technique is decidedly modern: she paints on hammered bronze imperfectly aligned, fracturing the image, ironically modernizing it, perhaps, after all, to imply that it is a hopeful mirage, a fantasy of the triumph of woman. But whether reclining at the bottom of the painting, as she is in one work, or standing upright at the side of the painting, which she is in effect introducing to the audience, like an impresario in a theater, she points to—with her feet when she is reclining—a classical row of columns, the remains of a façade of a classical temple, an allusion to antiquity, just as Venus is. Dare one say, no doubt too speculatively, that the upright columns, repeated emphatically, are phallic in import—not just a very oblique allusion to a man, perhaps even Mars, the marriage of the goddess of love and the god of war indicative of peace on earth—but imply that Cranach’s thin, upright, small-breasted Venus is a so-called phallic woman? A phallus is a symbol of power, and a goddess—Venus—is all powerful. The idea that she is implicitly a male certainly explains her boyish body. Her small breasts are pro forma additives to an adolescent boy’s body. “Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of love, is often considered an ally to lesbians, and her male form, Aphroditus, was worshipped on Cyprus.” Yamaguchi’s Venus is a not so “innocent bystander,” as the subtitle of the exhibition says she is.

Broadly speaking, Yamaguchi’s works are pastoral allegories of death in paradise, with an oblique affinity to Poussin’s Et in Arcadia Ego, except that Yamaguchi’s Arcadia has seen better days in myth, just as her Venus has seen better days in antiquity and, for that matter, in Cranach’s paintings. But what gives Yamaguchi’s paintings a feminist edge is that they imply that woman was more highly regarded and treated more respectfully in traditional art–she was a goddess--than in so-called avant-garde art, where she is a victim of male sadism. Duchamp, Picasso, Ernst, De Kooning et al may advance art, but they are misogynist and emotionally vicious. WM

Takako Yamaguchi, Innocent Bystander April 11 - May 31, 2025, Ortuzar Projects New York, NY

Donald Kuspit

Donald Kuspit is one of America’s most distinguished art critics. In 1983 he received the prestigious Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinction in Art Criticism, given by the College Art Association. In 1993 he received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Davidson College, in 1996 from the San Francisco Art Institute, and in 2007 from the New York Academy of Art. In 1997 the National Association of the Schools of Art and Design presented him with a Citation for Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts. In 1998 he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2000 he delivered the Getty Lectures at the University of Southern California. In 2005 he was the Robertson Fellow at the University of Glasgow. In 2008 he received the Tenth Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. In 2013 he received the First Annual Award for Excellence in Art Criticism from the Gabarron Foundation. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Fulbright Commission, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim Foundation, and Asian Cultural Council, among other organizations.

view all articles from this author