Whitehot Magazine

October 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

October 2025

A Cold, Solemn Generation Speaks — Beijing, China

Thank You, Have a Nice Day! Installation View. 2025

Thank You, Have a Nice Day! Installation View. 2025

By SERENA HANZHI WANG October 18th, 2025

I didn’t expect a polite phrase to hit me like a warning. Walking into Thank You, Have a Nice Day! – a group show by four Gen-Z Chinese artists – the customary pleasantry of the title felt less like a friendly send-off and more like an automated voicemail from society. The gallery space itself is cold and solemn: low lighting, sparse arrangements of strange objects, and a chill in the air as if the AC was set to “mausoleum.” It’s the kind of environment where a “Have a nice day!” echoes with dark irony.

The four artists spend formative years straddle China and North America, physical and digital realms, hope and cynicism. In here, niceties are suspect, and the mood is a far cry from warm. It’s as if each work murmurs under its breath: “Thank you… we’re not OK.”

①

Xulin Li, There Is No Need To Blame, Video/Installation/Image/Performance, 10 minutes, variable dimensions, 2024-2025

Xulin Li, There Is No Need To Blame, Video/Installation/Image/Performance, 10 minutes, variable dimensions, 2024-2025

The first thing I encounter is art works by Xulin Li. Growing up in Beijing, Li witnessed how order can feel both comforting and absurd: the security guards stationed at every gate, the endless grid of synchronized traffic lights pulsing like a mechanical song, the constant hum of surveillance and progress. It’s a city where things function almost too well, where efficiency itself begins to feel surreal. His work taps into this suffocation of routine and regulation — from the small rituals of daily life to the vast architecture of the system itself.

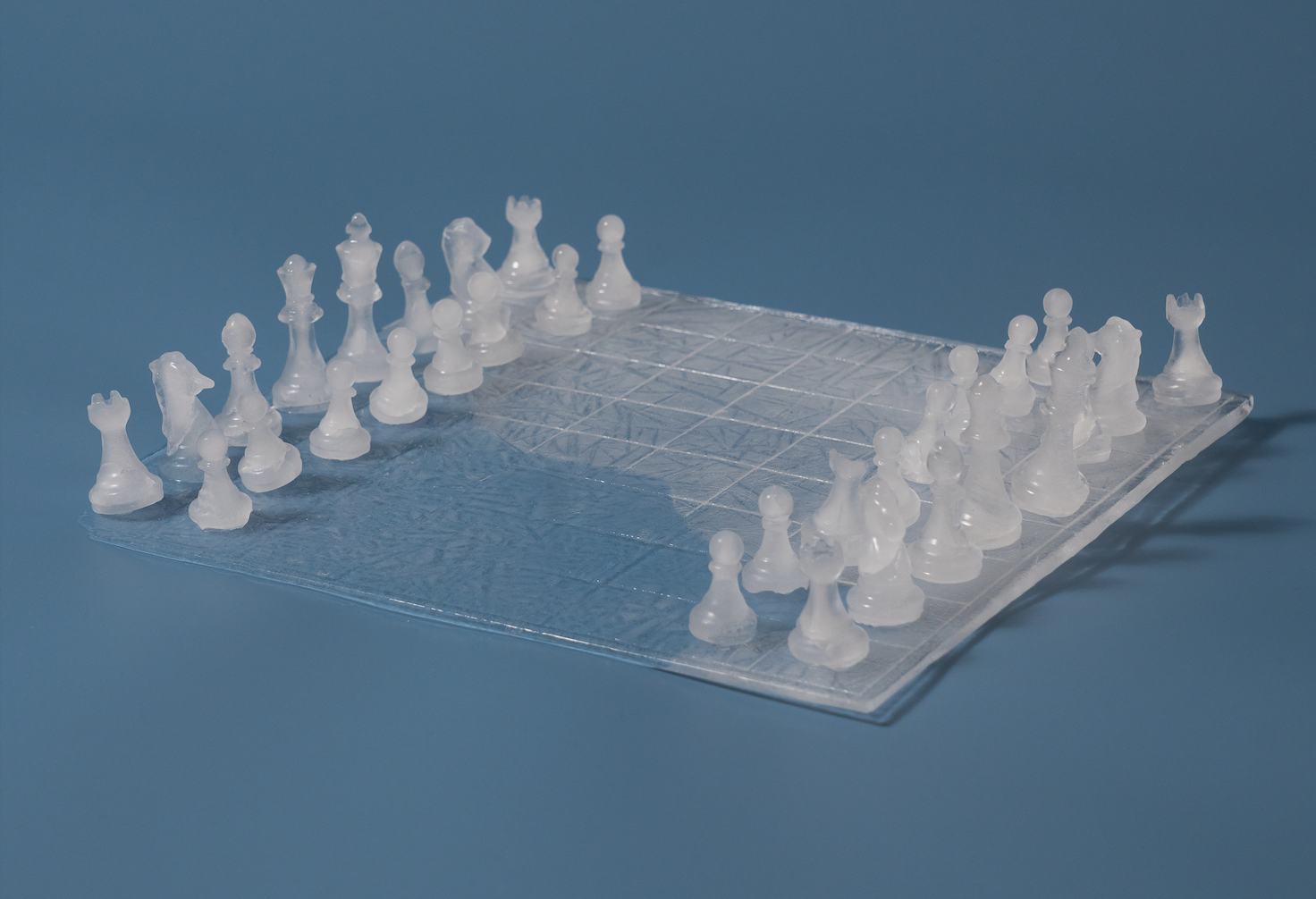

His There Is No Need to Blame (2024–2025) takes form through performance-base sculpture: a father and son play chess with pieces made of ice. The match is quiet, almost too polite, until the pieces start to melt. Soon the board is slick with water, and the rules — chess rules, or maybe just the idea of rules — begin to fall apart. The title says it simply: there is no need to blame anyone.

Visually, the piece is minimal — its only material is ice. But that’s what makes it so strong. It’s fragile, temporary, and full of meaning that never quite announces itself. Li taps into that East-Asian sense of negative space, where silence and absence speak just as loudly as what’s in front of you. Everyone who sees it will project something different onto it, and that’s exactly the point. The work leaves you in that quiet pause, just watching, as the order you thought you understood slowly melts away.

Beside it, Overdrive (2025) captures a small, perfectly trimmed buxus — a common ornamental shrub in northern China — speeding down an empty highway. The footage mimics traffic-camera surveillance, complete with timestamp and violation code, as the green sphere is caught “breaking” a speed limit. The absurdity is immediate: an object of stillness and order turned fugitive. In its perfect symmetry, the shrub looks almost digital, like a simulation glitch escaping the system that shaped it. The humor is dry, but the undertone is harsh. Overdrive stages rebellion as a simple act of motion — an ornamental lifeform breaking free from its assigned stillness.

Through these two works, Li slows time down rather than speeding it up. He looks at how order and chaos coexist — how structure can be both comforting and absurd. The ice melts, the shrub races forward; both are caught in quiet cycles of persistence and release. His works don’t offer answers or manifestos, only offer awareness. What remains is a gentle truth: sometimes all we can do is keep watching, and accept that control was never the point.

②

Chenchao Ma. Stress Test Series. Installation View. Includes: Blue Photogram, 30 x 40cm*6, Photography Prints, 2025

Chenchao Ma. Stress Test Series. Installation View. Includes: Blue Photogram, 30 x 40cm*6, Photography Prints, 2025

Later I notice this a wall of blue — eight cyan-toned prints arranged in a grid, their shapes hovering like apparitions. These are Blue Photogram (2025), Chenchao Ma ’s series of pseudo-scientific images depicting anti-riot tools — the kind of cheap, mass-produced poles and large clamps you might find on Alibaba or in the hands of security guards at residential compounds. Beside them stands a clear riot shield labeled “FANG BAO (anti-riot)”. Together, they set the tone for Ma’s body of work — dry, cold, yet unmistakably dramatic.

Chenchao Ma, Witness, 80 x 60cm, Art Micro Spray, 2025

Chenchao Ma, Witness, 80 x 60cm, Art Micro Spray, 2025

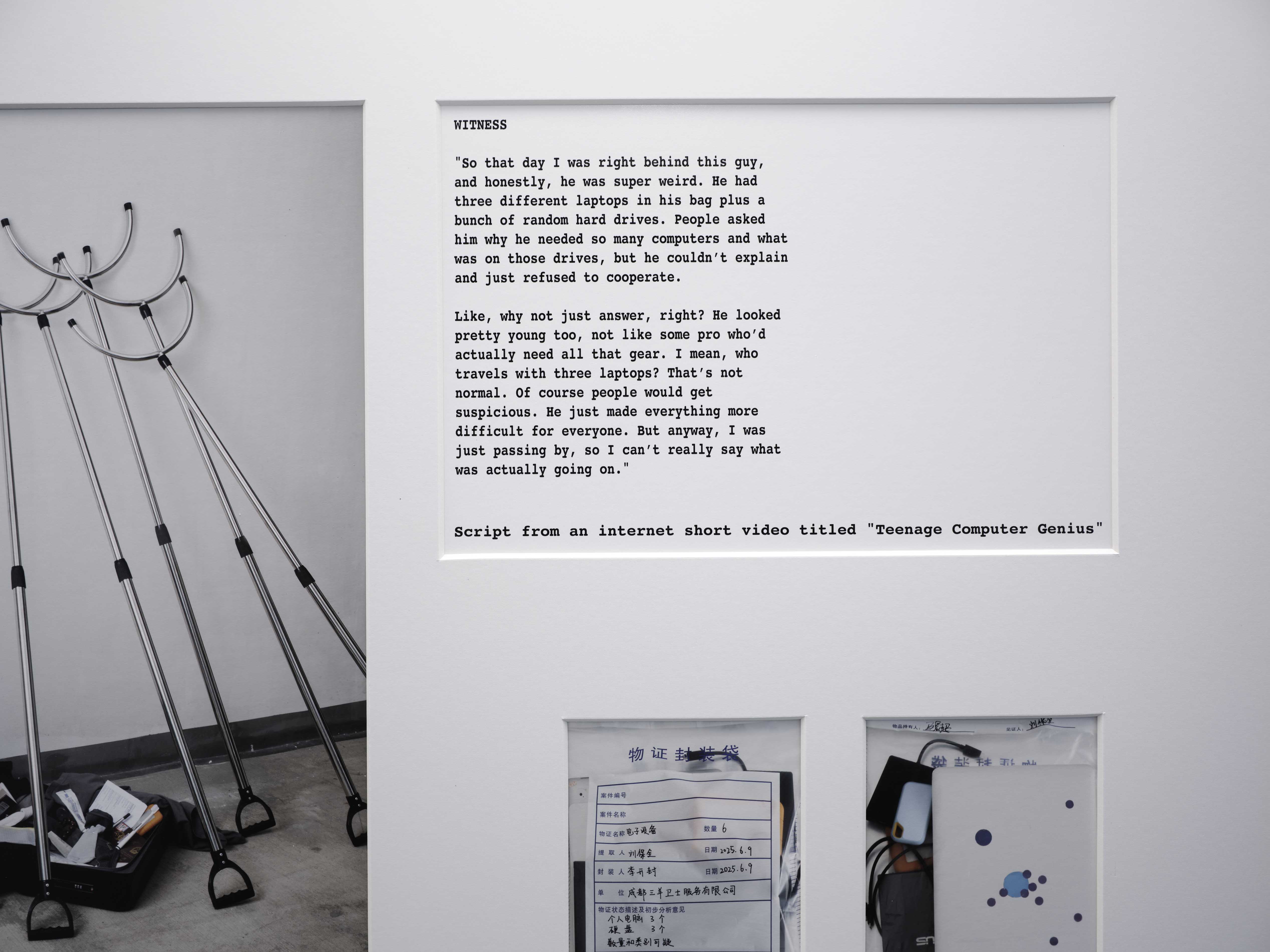

Next to these, Witness (2025) distills that tension into language. In a transcript from an online short video, an innocent bystander recalls a young man being stopped by security guards and questioned for carrying “too many laptops.” The story is mundane, almost laughable, yet it mirrors the same paranoid logic that fuels everyday life — a pseudo cop enacting a pseudo-disaster. The overkill is the point.

It feels like I’ve stumbled onto the set of an ironic anti-terror drill, a cosplay of fear. Ma’s work hits a nerve because it’s not just about China or anywhere in particular. Growing up, I saw rent-a-guards in ill-fitting uniforms manning metal detectors at malls and subways, performing safety routines everyone knew were for show. In the U.S., my college made us hide in dark classrooms for “active-shooter drills,” as if the act of pretending could ever protect us. Ma’s work distills these memories into a single absurd vision — a reality where the machinery of protection exists mostly to prove it’s still working.

③

Nanding Hao, Scraps Variation, 45 x 60cm, Phtotography Print, 2025

Nanding Hao, Scraps Variation, 45 x 60cm, Phtotography Print, 2025

Across the gallery, Nanding Hao’s Temporary Residence (2025) offers a quieter kind of unease. Her photographs feature fragile constructions made from cardboard boxes, stacked suitcases, and other symbols of mobility — objects that seem to wait for departure even as they stand still. The materials are humble, disposable, yet they carry the gravity of someone’s life.

The work stems from Hao’s own experience. During the first months of COVID, while she was away on a short trip, travel restrictions sealed her off from her student apartment in Hong Kong. Everything she owned remained there, untouched — a room frozen in another city, another version of herself. Years later, she began reconstructing that absence through these images, turning memory into architecture.

Nanding Hao, Compression, 60 x 60cm, Phtotography Print, 2025

Nanding Hao, Compression, 60 x 60cm, Phtotography Print, 2025

What moves me is how unsentimental it feels. Temporary Residence doesn’t dramatize loss; it observes it with the calm precision of someone who’s learned to live with impermanence. The photographs speak to a generational state of transit — the sense that home is provisional at best, that stability is a story we tell ourselves. For those of us who grew up after 2000, permanence feels almost nostalgic. We move between dorms, sublets, and borrowed rooms, carrying our lives in suitcases, never fully unpacking.

Chenchao Ma and Nanding Hao both hint at society phenomena, yet their sensibilities come from different places. Ma works within a lineage of institutional critique and absurd performance, turning systems of authority into theater. His pseudo-security photography recall Santiago Sierra, who exposes the cruelty embedded in labor and control, as well as Ai Weiwei and Cao Fei, who transform bureaucratic language into performance. Through Ma’s lens, the rituals of enforcement become farce — a dark comedy of fear and obedience. Nanding Hao, by contrast, belongs to a quieter narrative tradition rooted in migration experience and memory. Her fragile constructions echo Do Ho Suh’s translucent fabric homes, meditating on the instability of “home” itself. Yet Hao’s version feels lighter, more generational — a foldable home for an age of precarity.

④

Zongchi Xu, Open Wound, variable size, Phtotography Print + Sculpture made of gauze, blood, and fishing wire, 2025

Zongchi Xu, Open Wound, variable size, Phtotography Print + Sculpture made of gauze, blood, and fishing wire, 2025

Zongchi Xu, Open Wound, Detail shot of the sculpture end part, 2025

Zongchi Xu, Open Wound, Detail shot of the sculpture end part, 2025

Rounding out the show, Zongchi Xu traces the invisible injuries of discipline that shape a generation’s inner life. His Open Wound (2025) series sits quietly in a corner, yet it draws you in with a discomfort that feels almost surgical. The photograph presents a pale, lucid surface where gauze fragments drift weightlessly. Hanging in front of it is another part of Open Wound — a sculptural installation where a single strand of gauze descends from ceiling to floor. It trembles slightly, as if breathing. Near the base, the thread is anchored by a thin metal needle that pierces the floor, gathering a small pool of dark red liquid around its point. The gesture is minimal but devastating: pain given structure, suspended between air and gravity.

Zongchi Xu, Paper Butterfly, 185x48cm (three peice total), three channel video installation, 2024

Zongchi Xu, Paper Butterfly, 185x48cm (three peice total), three channel video installation, 2024

Turning inward, Zongchi Xu traces the invisible injuries of discipline that shape a generation’s inner life. His three-channel video installation Paper Butterfly (2024) unfolds in rhythm, almost ritualistically. On one screen, a blackboard repeats the phrase “你总是想太多” — you think too much — written and erased in looping chalk. On another, a small silver bell rests on a desk; each time it rings, the artist folds and unfolds the same sheet of paper. The motion loops quietly, turning obedience into choreography — an act of discipline disguised as creation.

Nearby, Butterfly Unfolded (2024) translates that repetition into stillness. Nine squares of folded and unfolded paper appear in grayscale, their creases intersecting like fault lines. Each fold feels like a reflex — the muscle memory of restraint. Together, they form a psychological map: the geometry of repression and release.

Zongchi Xu, Butterfly Unfolded, 60 x 80cm, Paper Art, 2025

Zongchi Xu, Butterfly Unfolded, 60 x 80cm, Paper Art, 2025

Standing before these works, I’m reminded of my own generation’s relationship with pain: how we’ve learned to aestheticize it, to sanitize it until it feels manageable. Xu doesn’t offer that comfort. His images hum with the low frequency of endurance — that quiet noise beneath our daily performance of being “fine”. The gauze line sways slightly in the air-conditioned room, and for a moment I think it’s alive. Maybe that’s the point. The wound isn’t closing; it’s still breathing. In this way, Zongchi Xu extends a lineage that runs from Wolfgang Tillmans, who transforms surface and light into feeling, to Kiki Smith, who mapped the anatomy of vulnerability with scientific tenderness. Like them, he turns intimacy into matter — proof that a wound, however quiet, can still speak.

These four young artists want you to imagine the worst about our future, not as spectacle but as something ordinary, the quiet collapse already threaded through how we move and speak and try to stay alive, the kind of fear that looks like protection and the kind of control that calls itself care. They come from Beijing, Sichuan, Inner Mongolia, and Yunnan, each tracing a different form of collapse, and together they make it feel collective.

Thank You, Have a Nice Day! - Sep 13th - Oct 23th, 2025

Timeless Essence Gallery, Unit 1202, South Tower, Shangdu SOHO, Chaoyang District, Beijing, China

Artist:

马晨超 Chenchao Ma (b.2004)

郝南丁 Nanding Hao (b.2003)

徐纵驰 Zongchi Xu (b.2001)

李胥霖 Xulin Li (b.2006)

Curator:

岳丘山 Kevin Yue

王天羲 Tianxi Wang

王涵芝 Serena Hanzhi Wang

Serena Hanzhi Wang

Serena Hanzhi Wang (b. 2000) is an award-winning art proposal writer, multimedia artist, and curator based in New York City. Her work spans essays, exhibitions, and installation Art—often orbiting themes of desire and technological subjectivity. She studied at the School of Visual Arts’ Visual & Critical Studies Department under the mentorship of philosophers and art historians. Her work has appeared in Whitehot Magazine, Cultbytes, SICKY Mag, Aint–Bad, Artron, Art.China, Millennium Film Workshop, Accent Sisters, MAFF.tv, and others.

view all articles from this author