Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

“Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention” Sets Painting and Poetry in Motion at NCMA

Grace Hartigan in 1953 seated in front of River Bathers. Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

Grace Hartigan in 1953 seated in front of River Bathers. Special Collections Research Center, Syracuse University Libraries.

By STEPHEN WOZNIAK June 2, 2025

“Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention,” an extraordinary new traveling exhibition featuring many of the artist’s acclaimed mid-century Abstract Expressionist works, is long overdue. Unlike the career-spanning surveys of Hartigan’s work presented at the Neuberger Museum of Art and the Museum at Guild Hall several decades ago, this exhibition—curated by Jared Ledesma at the North Carolina Museum of Art—focuses on a more concentrated period. It showcases a masterful selection of 45 paintings, collages, prints, and other art objects from the 1950s through the early 1960s, highlighting both celebrated and rarely seen works created during her time in New York City. A critical focus of the exhibition is the network of influential relationships and collaborations Hartigan maintained with revered contemporary poets and close friends, including Frank O’Hara, James Merrill, and Barbara Guest.

Grace Hartigan, Bray, 1954, oil on canvas, 60” x 50”. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of William Inge.

Grace Hartigan, Bray, 1954, oil on canvas, 60” x 50”. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri, Gift of William Inge.

The two-gallery show opens with Hartigan’s sizeable, gestural oil painting Bray, from 1958. It features a collision of the artist’s signature hulking outlines, brushy swaths of azure, upended verdant spires and an unfolding biomorphic yellow form—all leaning toward pure abstraction. However, figurative fragments quickly emerge: a bellowing brown equestrian face, baring teeth and a ruddy tongue, turns toward the sky above, perhaps crying out for escape from the street duty that workforce horses endured in cities and rural locations at the time. The painting, it turns out, resulted from Hartigan’s European travels earlier that year, including a stay in the small coastal town of Bray, Ireland. The painting’s title offers a quaint play on word meanings, borne of brash ambiguous forms and intriguing convoluted imagery. Bray is a tempestuous unfurling and piling of paint—a splashy performance of primal action and reaction—though never merely figure and ground. Instead, it suggests the inextricable morass that defines the life we choose—and that which we do not.

Grace Hartigan, Grand Street Brides, 1954, oil on canvas, 72 9/16” x 102 3/8”. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from an anonymous donor.

Grace Hartigan, Grand Street Brides, 1954, oil on canvas, 72 9/16” x 102 3/8”. Courtesy of the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from an anonymous donor.

On the opposite wall hangs Hartigan’s most famous oil painting, Grand Street Brides. Animating the frozen fakery of the daze-faced mannequins featured, Hartigan laid her hefty feral strokes and sliding washes of emerald, mustard and fuchsia upon the mottled dresses of her assembled “women” to give them life within the lie of storefront display merchandising. Her handling of the medium is remarkable: its tangle of smeared skeins, scraped smudges and hazy radius marks remind us that she exceeded lessons in sharded figurative subdivision learned from Picasso and de Kooning, aligning more with the post-Fauvist canvases of Henri Matisse and the wistful, contemporaneous painterly pop of Larry Rivers. Grand Street Brides, in many ways, was Hartigan’s quiet objection to protected patriarchy and the social norms of male ascendance. But the painting was also awash with strength in numbers; its band of intemperate protean women braced for—and ready to cast off—matrimonial affectations and ideal wifely lifestyles set upon them. It’s a complex piece, equally important then as it is now, rife with uncanny order, vibrating chaos and maybe even a hint of irony.

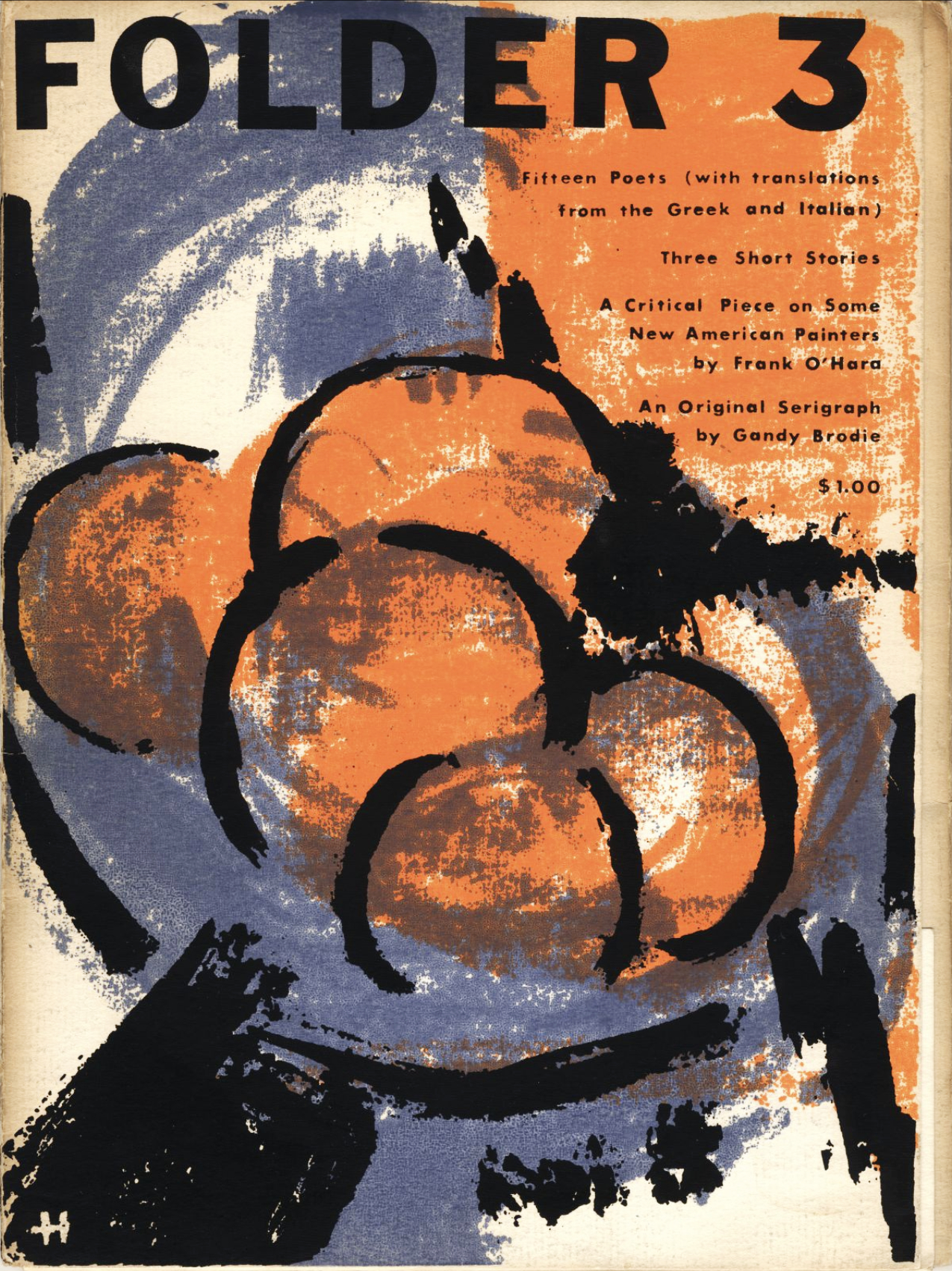

Folder, no. 3, 1954, featuring cover art by Grace Hartigan and a critical art review by Frank O’Hara.

Folder, no. 3, 1954, featuring cover art by Grace Hartigan and a critical art review by Frank O’Hara.

An important aspect of the exhibition is the visual and written evidence of Hartigan’s immediate social and creative circles, which exerted a pronounced influence on the artist and her work. Instead of consummate collaboration, however, Hartigan regularly created artworks inspired by the wordcraft and personal presence of her peers, like poets O’Hara and Guest.

One such work is Hartigan’s screen-printed cover art for the literary and aesthetic publication Folder, no. 3, from 1954, which featured a mound of muscular, shadow-seated oranges atop a brushy abstract blue bowl. That specific edition of the magazine also included “A Critical Piece on Some New American Painters” by O’Hara, as well as an original serigraph, among other written and visual content.

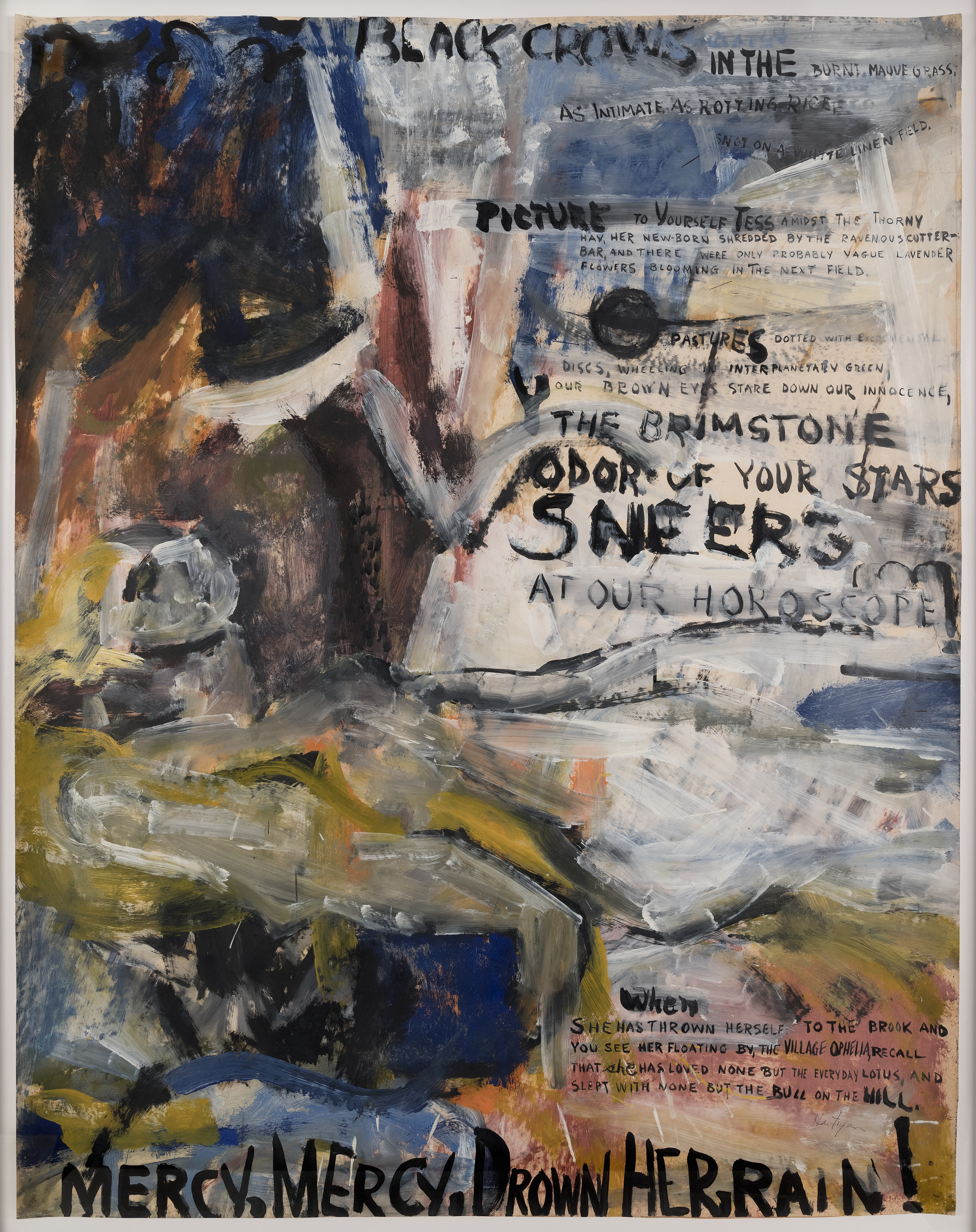

Grace Hartigan, Black Crows (Oranges No. 1), 1952, oil on paper, 44 ¼” x 33 ½”. University of Buffalo Art Galleries: Gift of the David K. Anderson Family, 2000.

Grace Hartigan, Black Crows (Oranges No. 1), 1952, oil on paper, 44 ¼” x 33 ½”. University of Buffalo Art Galleries: Gift of the David K. Anderson Family, 2000.

In 1953, Hartigan created the oil on paper Oranges: 12 Pastorals for the cover of O’Hara’s 18-page poetry book of the same title—a strikingly similar image to the Folder magazine cover. And only a year prior in 1952, Hartigan created its likely progenitor Black Crows (Oranges No. 1), also in response to O’Hara’s poetry, itself a nod to Shakespeare’s death-of-Ophelia passages in the play Hamlet.

The frumpy layers and folds of brown, gold and blue oils in Black Crows (Oranges No. 1) are covered in the inky, hand-hewn O’Hara poetry text that ebbs and flows—like the river water Ophelia tragically drowned in—along the lower and right side of the work. The piece features pertinent recurring themes in Hartigan’s oeuvre: the devastating impact of social pressures and the erosion of innocence and autonomy for women, as well as overarching themes of deterioration and death, as presented in the poem and play. The painted work, in some ways, highlights the here-and-now flesh and form of the text, more than offering a direct illustration of the literary sources it draws from. Black Crows (Oranges No. 1) helps to establish the evolution of more than a dozen nearby works in the show that focus on Hartigan’s foray into lithography, screen-printed editions and limited reproductions.

Grace Hartigan, Barbara Guest Archaics, 1968, ink and collage on paper. Courtesy of the Grace Hartigan Estate.

Grace Hartigan, Barbara Guest Archaics, 1968, ink and collage on paper. Courtesy of the Grace Hartigan Estate.

In 1961, Hartigan and close friend Barbara Guest were set to collaborate directly on a short series of black and white lithographs at Universal Limited Art Editions based on Guest’s Archaics poetry cycles. Both were fascinated by and identified with Greek mythological heroines, like Atalanta and Venus, featured in Guest’s poems. However, issues arose, delaying the production of Hartigan’s contribution of only four prints long after Guest’s text was separately published in full. Over the next few years, the friendship between the artist and poet began to fray—when the artist struggled with alcoholism and differences in their lifestyles became more apparent than ever. Around that time, Hartigan moved away from her New York creative circle to Baltimore, marrying art-collecting epidemiologist Winston Price and teaching at Maryland Institute College of Art.

By 1968, Hartigan utilized torn artist proof lithographic prints from the intended collaboration with Guest to create Barbara Guest Archaics. It features magazine advertisement cut-outs of faceless curled blonde hairdos; a headless, dress-wearing fashion model with umbrella in hand; orange feminine fingers in chunky costume rings gripping decorative ropes; baroque faux gold furniture details; blooming flowers and much more. On, in and around these pictures are Hartigan’s recycled print fragments, sloppy black marks and brushy washes, as well as the cursive text “end” and obscured “autumn” from the original poems—punctuated with a large question mark. Hartigan’s abstracted, Fall-hued, market-made, feminine magazine imagery somehow resonates with the Guest’s classic visualization, notably the woven rope and hair, evoking “You of the thick twist, like an earring/your hair, pendulous and closely welded.” At the same time, the piece reads like Hartigan’s critique of the urbane and insulated life that Guest led, as much as a Hartigan’s own settling down far away.

The people who populated Hartigan’s life and gestural paintings—often other artists, poets, intellectuals, collaborators, queer rebels, cultural outsiders—are of paramount importance. Their presence helped speak to questions about Hartigan’s cherished friendships, romantic unions and worldview, as well as personal expectations and perceptions about her as a woman—and her position as an artist. From a journal entry of the era, Hartigan indicated that her art addressed the “wildly discordant” ongoing event of “being together in the world.” “The figures in my painting ask, ‘What are we doing? What do we mean to each other?’” While these questions were raised directly by the artist, her work retained enough mystery to give it life long after it was first exhibited.

Ultimately, “Grace Hartigan: The Gift of Attention” provides viewers a solid, finite slice of history that defines not only this important artist but New York School painting at mid-century. After looking carefully through this exhibition and tracking the growth of Hartigan’s extraordinary precocious work, it is clear she reconfigured purist rules set by critical proponents of early Abstract Expressionism, incorporating popular recognizable imagery, the poetry of peers and, most importantly, the people who populated her life and works that helped define “what we mean to each other.” WM

Stephen Wozniak

Stephen Wozniak is a visual artist, writer, and actor based in Los Angeles. His work has been exhibited in the Bradbury Art Museum, Cameron Art Museum, Leo Castelli Gallery, and Lincoln Center, among others. He has performed principal roles on Star Trek: Enterprise, NCIS: Los Angeles, and the double Emmy Award-nominated Time Machine: Beyond the Da Vinci Code. He is a regular contributing critic for the Observer in New York City and writes essays for noted commercial art galleries and museum exhibition catalogs. He co-hosted the performing arts series Center Stage on KXLU radio in Los Angeles and guest hosts Art World: The Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art podcast in New York City. He earned a B.F.A. from Maryland Institute College of Art and attended Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. To learn more, go to: www.stephenwozniakart.com and www.stephenwozniak.com. Follow Stephen on Instagram at @stephenwozniakart and @thestephenwozniak.

view all articles from this author