Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

Starstruck and Conflicted: An Interview with Liza Jo Eilers by Phillip Edward Spradley - New York

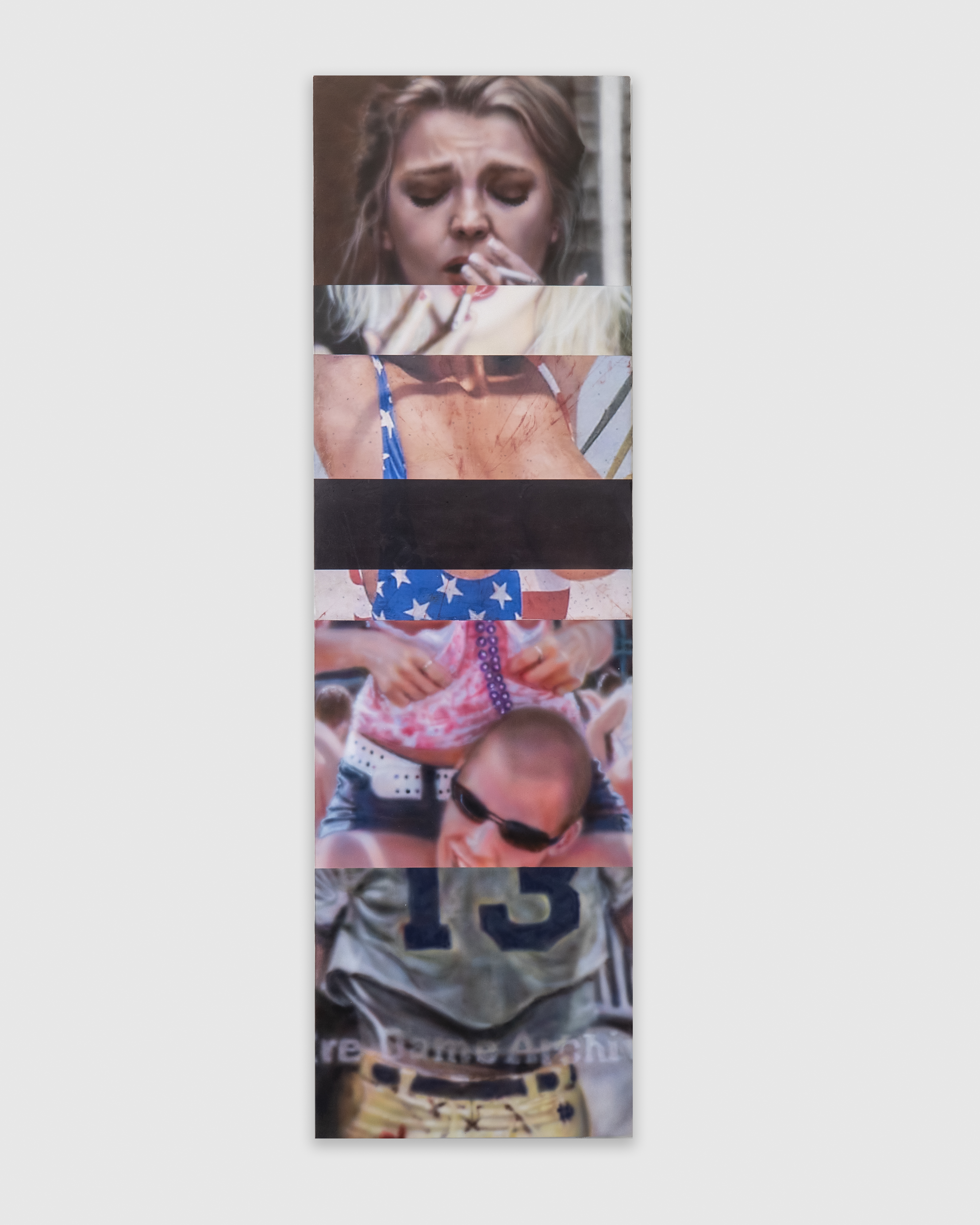

A way a lone a last a loved a long the, 2025. Acrylic, flashe, pigment transfer and glitter on linen, 18 x 89 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

A way a lone a last a loved a long the, 2025. Acrylic, flashe, pigment transfer and glitter on linen, 18 x 89 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

Liza Jo Eilers, Starland silver sash

GRIMM, New York

September 5 - November 1, 2025

By PHILLIP EDWARD SPRADLEY September 3, 2025

Beneath the weight of oppression, fear, and division, there still live the sparks of resilience: exclamations of hope, protests disguised as joy. That feels like the essence of America—the freedom to create, to sing, to perform, to open a vein and let the world see.

Liza Jo Eilers thinks about America this way too, not as a perfect promise but as a chorus of people who have dared to step into the light of their own making. Her new exhibition turns toward familiar figures who have poured themselves out for us: a voice that was both balm and blade, a performer who could move a nation with their tears, a raw and reckless presence commanding the stage as if it were the only place to breathe.

Each subject here is larger than life, but also achingly human. They remind us that to be an artist in America is to wrestle with contradictions: fame and loneliness, beauty and violence, adoration and critique. Eilers captures these tensions not only in who she paints but in how she paints them—cropped fragments, sudden interruptions, moments of concealment that draw as much attention as the spectacle itself. There is always something withheld, a gesture caught mid-motion, a face obscured just as it begins to reveal itself.

Eilers uses these maneuvers to suggest the ways women, in particular, are caught in the loop of being seen and seeing themselves, of performing and being performed upon. Pleasure here is never simple. It is laced with the mechanics of power, the demands of spectatorship, and the question of who, ultimately, the performance is for.

The figures Eilers conjures have opened themselves fully, exposing both strength and vulnerability, because they must. They are not untouchable idols but artists of resilience, individuals who remind us that to create is to protest, to declare hope, to build joy in the very face of despair. Her icons are radiant, imperfect, and utterly alive. Through them, Eilers invites us to remember that America is not just a place but a practice: an ongoing act of expression, rebellion, and love.

Detail | A way a lone a last a loved a long the, 2025. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

Detail | A way a lone a last a loved a long the, 2025. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

Phillip Edward Spradley: You have been remarkably consistent in your exploration in performance, visbility, and identity. How has this new sereis shifted or evolved your thinking and enagement with those ideas?

Liza Jo Eilers: This time around I’m diving more into fragmentation by splitting, doubling or obscuring, to show how visibility itself can be slippery, even manipulative. For this show, in particular, I’ve used long narrow horizontal and vertical canvases, which kind of suggests a film strip, creating interruption but also continuation. The idea that what you’re seeing many clipped moments from a longer performance. The image no longer arrives as something whole, but as something unstable, conditional, always changing. That shift makes the “performance” not only about theatrics but also about structure itself: the way an image appears, vanishes, and reconstitutes itself for whoever is watching. This instability feels true to our moment. What’s promised, withheld? What glimmers for an instant before vanishing, and what insists to last forever…if forever even exists.

The subjects you depict are icons of a particular era—many of whom are no longer with us. What is it about this time that continues to draw you in and feel urgent today?

The late 20th century feels like a turning point, when mass-media celebrity, MTV aesthetics, and tabloid culture taught us how to consume women as spectacle. Many of these things are gone, but the mechanics they embodied are still running. Really though, Is time just a donut? I return to them not out of nostalgia but because they feel like fossils of a machine, reminders that what passes as “new” is often repeating itself. I think what also draws me to these icons is that they show how performance itself can be political, it isn't just some PR message on instagram, it's something more embodied. It was a time where subcultures felt stronger, when community carried its own kind of resistance, I guess I’m looking back because I deeply long for that connection and I want to learn from it in the hope of finding my own.

True men, like you men, 2025. Acrylic, pigment transfer, thermochromic ink, gouache, iridescent ink and glitter on linen 60 x 18 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

True men, like you men, 2025. Acrylic, pigment transfer, thermochromic ink, gouache, iridescent ink and glitter on linen 60 x 18 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

Some of your paintings take the form of layered images, other include hidden elements, and some stand along as singular portraits. Do you have self imposed rules for deciding which approach to use, or is it more intutive?

I would say it’s intuitive, but also planned? In a sense that I am not always painting to work through painting problems but using tools like photoshop to help me test out different iterations. I’ve probably made a hundred versions of each painting. Lately I’ve felt one image feels too singular and I want to create more of a story versus a sentence, I want to make connections. It’s fun to play with the thermochromic or hydrochromic ink because it adds the element of time, temperature, touch into the work. They create an illusion of permanence and sometimes even create a new interpretation of the image entirely with only parts peaking through, a teasing of redaction.

The trickle down effect (mint), 2025. Acrylic, pigment transfer, and glitter on linen, 18 x 47 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

The trickle down effect (mint), 2025. Acrylic, pigment transfer, and glitter on linen, 18 x 47 in. Courtesy of the Artist and GRIMM, Amsterdam | London | New York. Photo credit: Mikey Mosher

How do you navigate the tension in your paintings between women viewed as objects of desire and as symbols of power?

You know, I’m still figuring it out, and that’s exactly why I paint. I’m not interested in resolving the contradiction per se but in staging it. For all I know, a woman may always be seen through the lens of desire, but I can recognize visibility can also be the stage of where she authors herself. What holds me is the tension between what’s visible and what’s invisible, the push and pull of what’s shown, what’s suppressed, and what can only be felt in between.

Phillip Edward Spradley

Phillip Edward Spradley is a cultural producer based in New York City.

view all articles from this author