Whitehot Magazine

December 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

December 2025

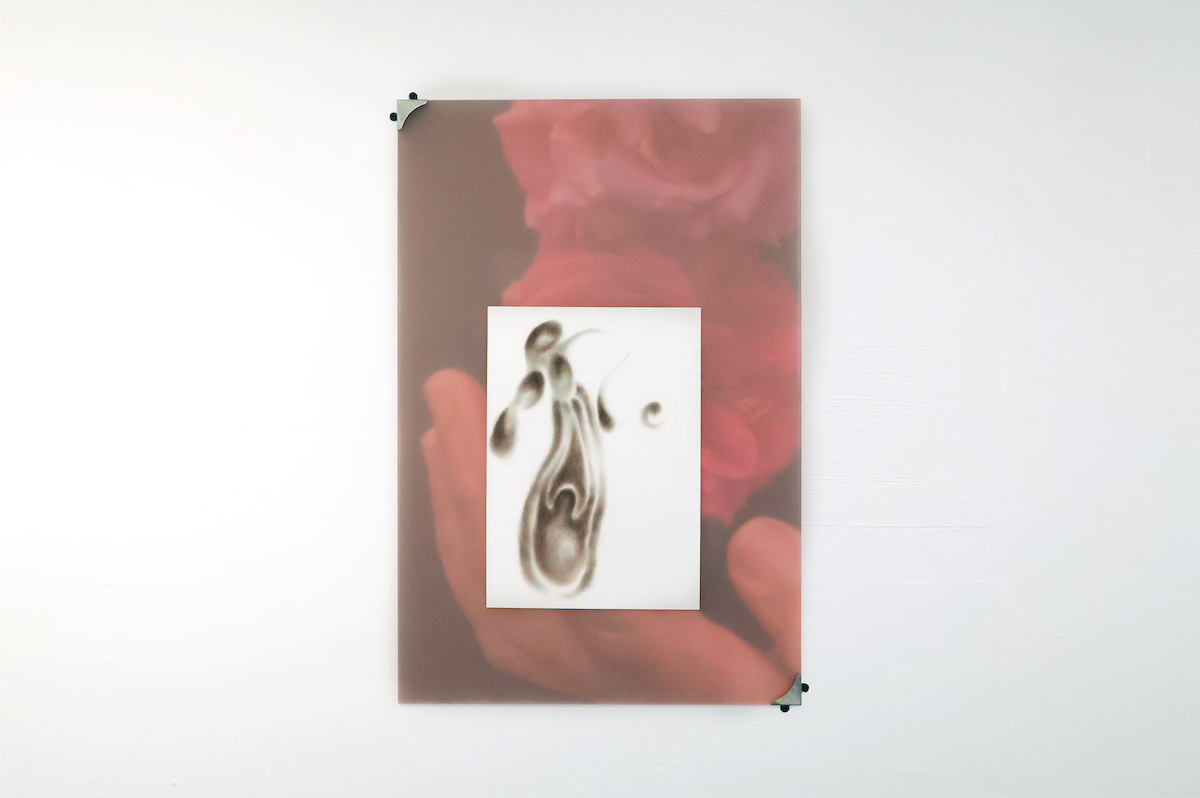

‘Instead, It Bore A Tulip’: Tawfik Naas at Bolding Gallery, London

Tawfik Naas, ‘Instead, It Bore a Tulip’, 2025, Bolding Gallery. Installation view.

By ARAM MASHARQA September 5, 2025

History, big History, is a generative problem because it is so impossible to describe, yet is the foundation for human culture itself. See Giambattista Vico, writing at the beginnings of humanism, essentially pitching the study of humanity: ‘our science ... comes to be at once a history of the ideas, the customs, the deeds of mankind’. For Vico, history is everything we have done and made, a thing which humans have actively shaped over time. We exist, and therefore history exists.

Edward Said, whose Orientalism wouldn’t have been possible without Vico, also thought a lot about history. Writing about the works of Joseph Conrad, a seafarer who wrote on the side, Said explains that ‘in its well-known indifference to the individual, history exactly parallels the sea's colossal indifference … [t]he transition in background from wide expanses of water to wide expanses of time was easily made’. Said understood the individual as a sailboat atop a wide ocean, able to move, navigate, make strides, but ultimately bound by the unrelenting back-and-forth of the ocean’s waves.

So big History lives through its metaphors. Tawfik Naas’ recent exhibition, Instead, It Bore A Tulip (Bolding, 19 July - 2 August) documents a process of searching for a new kind of metaphor. Tawfik’s body of work itself arises out of a long-term research practice, unravelling, unfolding, and boundless just like the histories it seeks to describe. The title is taken from one of the Tawfik’s accompanying written pieces, ‘The Shield Has Two Sides’, where he writes, ‘[i]n the summer of 1997, Libyan Botanist ------ observed a curious anomaly on the stem of a cluster of unripe yellow dates. Among the developing fruits, one had not formed a date at all - instead, it bore a tulip’. It speaks to a moment of deviation, called atavism in biology, where a trait or characteristic reappears in an organism after being absent across generations, suggesting the trait’s presence in a distant ancestor. Here, history is not the ocean, is not man made, but is the haunting surprise of finding a tulip amongst dates.

Tawfik Naas, A/Scented, 2025. Eyeshadow on paper. 40x60x0.5cm.

Tawfik Naas, A/Scented, 2025. Eyeshadow on paper. 40x60x0.5cm.

Discussions of the show often begin, as I did, from the big picture: locating its place within his larger research practice; explaining the Libyan historical context’s role in the work, and in the migration of his family. Yet, the works themselves are remarkable for their beauty, the softness of their colour and form. Many of the 2D works might resemble diagrams, but far from cold and skeletal, the forms are gestural and sensual, borrowing from the visual language of plants and the physical world.

Bolding Gallery explain that ‘Naas presents a new body of 2D work that signals a shift from research as a tool for understanding to research as a foundation for belief’. Instead, It Bore A Tulip is not a means to some enlightened end, but rather seeks to meet these physical forms on their own terms. To believe in the abstract shapes of the natural world is to invite the possibility that these are as true as anything humans could imagine.

Equally as true as a natural form, is the form of speech. We say something is idiosyncratic when it is singularly unique to the person, and the word idiom is defined by its untranslatability. Hearing an idea take shape on the tip of someone’s tongue can have no proper substitute, and so I met with Tawfik to discuss his work further. All direct quotation below is from him.

Tawfik Naas, “Hand”, “Seed”, “Water”, “Tulip In Hand”, 2025. Pencil on paper on perspex. 80x70x0.5cm.

Tawfik deals with history and biology, but as he is often quick to point out, he is not a historian nor a biologist. ‘Science and history are flawed because people are flawed and the people that tell us about science and history are people’. Underpinning the work, then, is a recognition that biology and history as told from a human standpoint is never a complete picture: ‘it’s purely conditioned to how we see the world and not how the plants understand the world, or the bacteria, insects, birds, or other forms of physical life’. Instead, It Bore A Tulip opens up the possibility that the perspective of these lifeforms offers equally valid frameworks and structures to understanding the interlocking, interweaving of past and present.

In our conversation, he opens describing two similar but different processes: dissecting and metabolising. ‘I’ve dissected this thing, but it’s not because I’ve tried to get to the details of it. It’s because I’ve tried to open it up; I’ve tried to see how expansive it can become’. This recontextualises even the forms in the show resembling cross-sections of plants and flowers. If the object of traditional history is to reach the kernel of truth, this work shows a process of creating the space around the object for it to speak for itself.

Tawfik Naas, Unfolded 1, Unfolded 2, Unfolded 3, 2025. Pastel on paper. 42x29.7cm (unframed).

Tawfik Naas, Unfolded 1, Unfolded 2, Unfolded 3, 2025. Pastel on paper. 42x29.7cm (unframed).

A whole host of digestive metaphors populate Tawfik’s language, with metabolising at the heart. ‘If we really lay it out flat, the work of the historian or the scientist is to do the digesting and metabolising for you’. Rather than just regurgitate these processes for an audience, Tawfik’s work invites audiences to also go through the work of metabolising for themselves. Thus the aesthetic of the visual work can feel abstract, esoteric, or as if something is concealed. Even when there is accompanying text, it is not a simple representation of everything he has read: the reader must also search for clues, infer meaning.

The research itself, a long-term project now in its eighth year, appears to mirror these processes of digesting, repurposing, metabolising, and movement between states of matter. Part of this is practical: ‘maybe this is just a process of archiving ... an admin thing, making sure that everything is traceable’. Another part is unintentional, as the research into atavistic, non-linear historiography bleeds into the work itself. Visual metaphors, lines from accompanying texts, all repeat and resurface. The text where the show’s title is found, The Shield Has Two Sides, existed in an earlier form at a show I curated earlier this year. That text then found its way into the Bolding show alongside extracts from his readings this year at Soup Gallery. ‘It’s about what it means to build dimension to something, what it means to flesh something out ... to support its integrity as a body of work’, Tawfik explains to me, and although ostensibly it has little bearing on the work in the show, I can’t unhear the continuation of this metaphor: digesting, metabolising, all to build up the body’s flesh.

But I’m not barking up the wrong tree (the show is called Instead, It Bore A Tulip; there are no wrong trees). Tawfik is slowly building and consolidating a living history, which takes its cues from the natural world, where evolution never existed as linear and difference was never mutually exclusive. The body of work is alive because it deals with things which are alive. A befitting coincidence: the show was held in a gallery housed within an antique market, and Tawfik recently discovered that the grandfather after whom he was named, owned an antique shop in Libya. Coincidences are often a surprise, are beautiful and strange, and resist explanation. The same can be said for Tawfik’s work, and also for seeing a tulip grow miraculously from the branch of a date tree.

Tawfik Naas, Instead, It Bore a Tulip, Bolding Gallery, July 19 – August 2, 2025.

Aram Masharqa

Aram Masharqa is a Palestinian-born writer and curator living and working in London. He holds gallery experience at both non-profit and commercial spaces across the city, as well as keeping a personal curatorial practice. Articles have appeared in magazines in London, and at Oxford and Columbia Universities. He graduated from the University of Oxford with a BA in English and is currently studying MA Contemporary Art at the Sotheby’s Institute of Art.

view all articles from this author