Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Voyage Into Infinity: As Glitch, Lubrication, and Momentum, Female Labor and the Obscured Body

By JUNTAO YANG January 29th, 2026

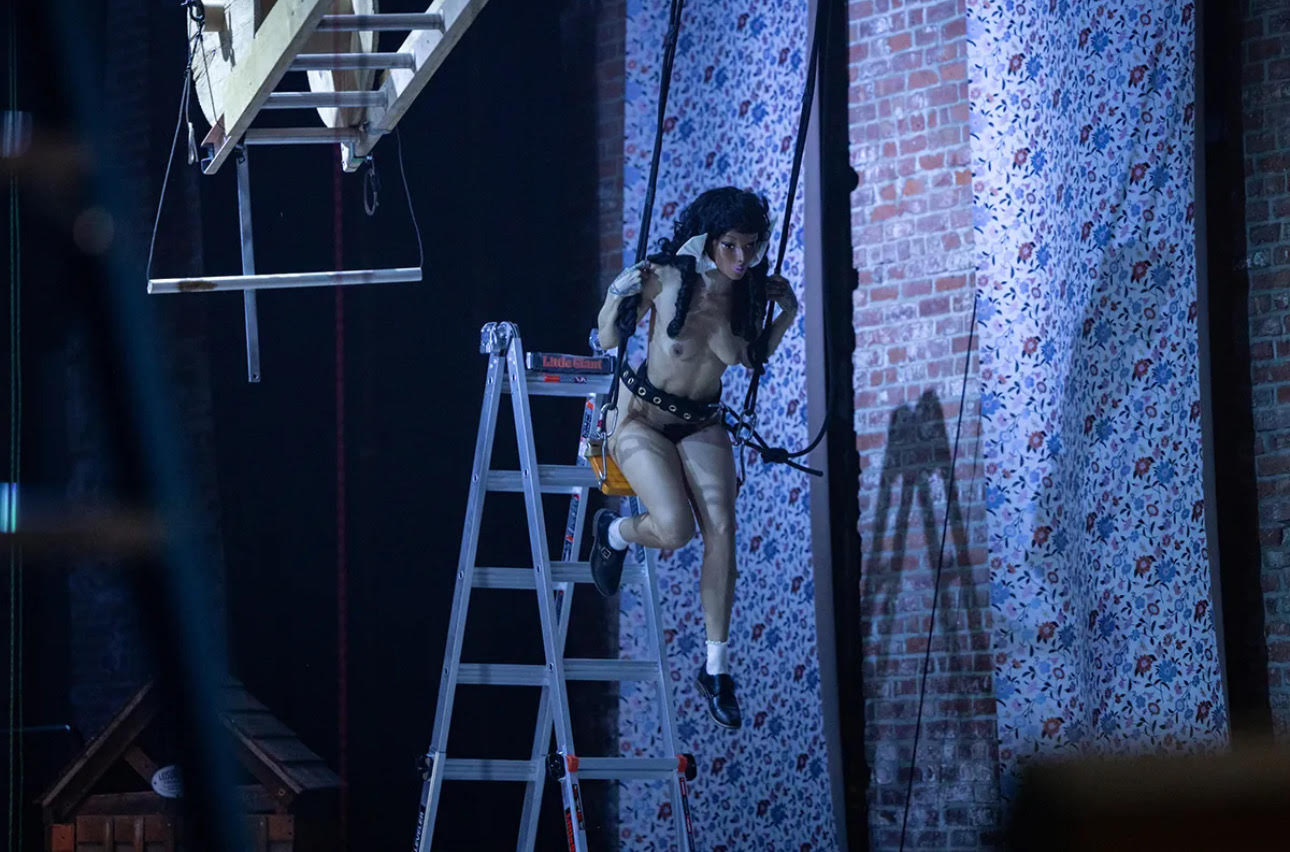

Voyage Into Infinity is an intermediate iteration of an artwork that will ultimately take the form of a performance video. In every sense, it boldly transforms the stage into a site where bodily actions negotiate, cooperate, resist, and contend with large-scale found materials. Narcissister describes this work as a deconstructive parody of Peter Fischli and David Weiss's video work The Way Things Go (1987), which, over its thirty-minute duration, presents a chain reaction of a large Rube Goldberg machine constructed from everyday objects such as tires, ladders, and soap. Rather than a formal appropriation, the ambition of Narcissister's work lies in marking a critical distance through a certain displacement—specifically, the displacement effected by the re-presence of the (female) body.

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

In The Way Things Go (1987), the artists deploy cool montage and other audiovisual means to splice together a series of segments originally filmed separately, striving to erase any evidence of human participation: non-human objects are endowed with their own agency, and physical laws unfold automatically. Tires roll, liquids flow, flames ignite—everything is staged to produce the objective allure of mechanical causality, even though this automaticity is in fact highly dependent on the human labor that has been edited out, along with countless adjustments and resets throughout the process. If Fischli and Weiss's original work aims, through its absurd yet exquisitely precise operation, to provoke metaphysical meditation on physical laws, causality, and non-human mechanicity, then Narcissister's feminist provocation attempts to toy with, even denigrate, that seriousness and rigidity, exposing the white male-centered clichés that underlie this obsession with objectivity.

By reintroducing pauses and ruptures into the interaction between intensely embodied naked bodies and the reconstructed apparatus, Narcissister creates on stage a non-theatrical suspense, bewilderment, and dread regarding potential failure, malfunction, and chaos. At such moments, the Rube Goldberg machine's operation stalls, awaiting the human performers' continuation, lubrication, or manipulation: the human performers are at once agents and patients, thereby erasing the divide between human and apparatus, or interrupting the discourse that strives to maintain such an imaginary. Due to the complexity of the apparatus and the performers' complete silence, it is difficult to anticipate how the next momentum will occur, to the point that one sometimes suspects one has witnessed a stage mishap. This tension and suspense constitute the primary affective force on stage, occasionally relieved by physical slapstick, reaching a pleasurable climax the moment the apparatus successfully operates (sometimes so rapidly as to dazzle). If we also consider the fetishism and voyeurism that the work makes explicit (through the apparatus in the foreground obscuring the main stage), the entire performance seems to intimate a consummation taking place.

Regarding this gamified intimacy between apparatus and human body, the core subversion of Voyage Into Infinity lies in bringing back into the light the human body and the force of materials themselves—both hidden from the camera in The Way Things Go—in order to restore the human labor and environmental resources upon which the mythologized mechanical objectivity depends. This myth of structural automaticity has, throughout the history of capitalism and racism, long been used to suppress and marginalize various forms of labor and natural materials, forcing them to be cheap or free in service of an imaginary of growth without cost (or of capitalist society's continued operation). Female bodies and labor, which need not be repaid, are crucial to the production and reproduction of growth—which is why such strenuous efforts are made to suppress claims upon these bodies and labors. The radical feminist history and discourse with which Narcissister seeks to converse has long delineated this: women are expected on the one hand to stay away from market-economy labor, while on the other hand being required to perform extremely cheap or even unpaid labor of care, maintenance, reproduction, and housework. These labors, in the name of care, both produce and reproduce. This is also why, in Voyage Into Infinity, the performers' actions are neither those of masters nor of pure patients. It is a story that begins with cautious negotiation with the apparatus as system.

In any case, attempting to converse with this radical legacy, a manifesto-like feminism runs throughout. When three female performers (wearing masks of different skin tones, dressed in European frocks) emerge from a cabinet in a corner of the stage, carefully holding candles to observe the massive apparatus composed of various found materials, they eventually pause and scrutinize a statue of a discus thrower at center stage—a symbol of the sublime power of the white male. Then, almost without warning, one performer uses her candle to burn through a cord on the object; as the originally balanced tension is disrupted, a huge sandbag plummets from above offstage, pulled to crash into the statue, which collapses with a thunderous noise. The female performers take turns standing in the statue's former position, mimicking the discus-throwing posture in comical fashion. Unlike the original, what they hold in their hands is no longer a hard discus or marble, but fragile porcelain plates. This prop unmistakably alludes to the weight of domestic labor (and a certain fragility that must be taken into consideration), replacing the sublime status of (male) human power that the discus thrower represents in art-historical canonical interpretation.

Nevertheless, in the Skirball iteration, the work chose to delete many overly symbolic feminist slogans, instead depicting struggle and hysteria in a somewhat more subtle, even childlike manner. In earlier iterations, there were passages where performers smeared lipstick almost maniacally over their entire faces and bodies, but these no longer exist here. Instead, this iteration embeds a scene in which a performer dances with a bundle of balloons tied to her wrists; the balloons are released, then pulled back down by tethers, repeated multiple times until the performer seems nearly exhausted, prostrate and gasping on the ground. Finally, as if weary of the game of chasing, releasing, and recapturing, the performers violently pop the balloons with their nearly spent bodies. This nerve-wracking passage is unrelated to the apparatus that constitutes the main body of the theater, closer to an aside commenting on the pursuit of freedom and the struggle with body and desire, ultimately pointing toward futility—a repetitive labor that leads to no result. But in any case, it intensifies attention and suspense regarding a thing or system on the verge of collapse.

Yet the process of construction remains lost; the conditions of the work's own production remain partially invisible. Although toward the end of the theater, the performers do clear away some debris, restore parts of the apparatus to their pre-triggered state, and right the toppled dominoes, the construction of the apparatus itself, even the collection and transportation of the large-scale materials, along with the labor behind it, are diluted and forgotten, thereby to some extent undermining the work's own claims. While these passages seem to suggest a powerful feminist effort—that after subversion, mischief, and wanton destruction, women ultimately commit to rebuilding, renewal, and starting over—what we ultimately witness is restoration to the original state, not creative editing or reinterpretation. Admittedly, to demand that all art about labor represent the entire process of labor would trigger an infinite regress toward ever-earlier labor that could have been shown (since any artistic practice necessarily involves framing and exclusion), thereby falling into an impasse of meta-commentary. But we can certainly imagine a different synecdoche from what is ultimately presented.

The theater's climax is undoubtedly when one performer (having shed all clothing) swings out from a high swing constructed by the apparatus, the backdrop suddenly parts, and amid intense lighting changes, a punk band assaults the entire space with its terrifying noise. The musician—who had been responsible for the grotesque, ethereal live score composed of montaged feminine vocal fragments accompanying the performance—pushes through an emergency exit to leave the synthesizer stage on the left side of the audience, transforming into the band's vocalist, whose dark metal voice completely reverses the preceding atmosphere. As I have intimated, if one views this work itself as a retrospective and meta-commentary on the history of feminist struggle, then this raw punk power, together with the performers' boundary-breaking interpretation, is undoubtedly the scene most directly and obviously paying homage to the surging radical art of the 1970s. That is: we will not hesitate to overturn everything. We will not hesitate to raise hell. In one passage that elicits gasps from the audience, a performer lies flat on a rotating wheel at center stage (the former position of the discus thrower statue), naked, with a lit sparkler inserted in her genitals, spinning rapidly on stage with the assistance of other performers, like some kind of ritual or celebration. This scene recalls the endless radical performances in the so-called experimental theaters hidden in the depths of downtown cafés and the attics of Eastern European immigrant dwellings in the 1970s—performances that were the spiritual symbol of a generation's movements for gender, racial, and sexual liberation and civil rights.

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Narcissister, Voyage Into Infinity. Photo by Walter Wlodarczyk. Courtesy of the artist and Pioneer Works.

Yet institutionalization is the lingering shadow cast over this work. Previously, in the Pioneer Works iteration, the theater took place in an open space where the artist's labor and action, as well as the audience's bodies and gazes, were all embedded within this three-dimensional apparatus, thereby allowing the theater's power to cede from the precision of causality to affect, desire, and embodiment. The proscenium stage of NYU's Skirball Center, however, weakened this semi-coercive invitation to the audience; its clear performer-spectator relationship merely enhanced the allure of stage spectacle. Moreover, as Narcissister herself has noted, earlier iterations' fifty-minute duration was often based on the limitations or requirements of various theater festivals and performance opportunities, while the NYU Skirball iteration's extension to eighty minutes was due to venue programming (and New York nightlife entertainment demands). This malleability in accommodating institutional frameworks significantly diminishes the work's radicality: in many scenes, the suspense and anxiety about the apparatus's operability, due to delays in performance actions, turned into hesitation, then boredom.

This threat of institutionalization becomes a regrettable footnote to radical performance, which is perhaps why the final scene feels like a memorial to a time and space already past, when unfettered radical subversion still had room: as the band falls silent, lights dim, the performers rearrange their clothing and climb back one by one into the cabinet from which they emerged; the remaining performer raises her candle, once again examining each part of the apparatus that they have agitated and somewhat restored, finally blowing out the candle, returning to whence she came, and closing the cabinet door.

Juntao Yang

Juntao Yang is a scholar, critic, and artist based in Brooklyn, holding an MA from Columbia University’s School of the Arts and a BA from Wuhan University. Yang's critical writings and artistic practices examine the operations of micro-power in visual and material culture, exploring the invisible conflicts of daily existence and the fluid mechanics of power dynamics.

view all articles from this author