Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Janet Fish, Phenomenal Still Life Painter by Donald Kuspit

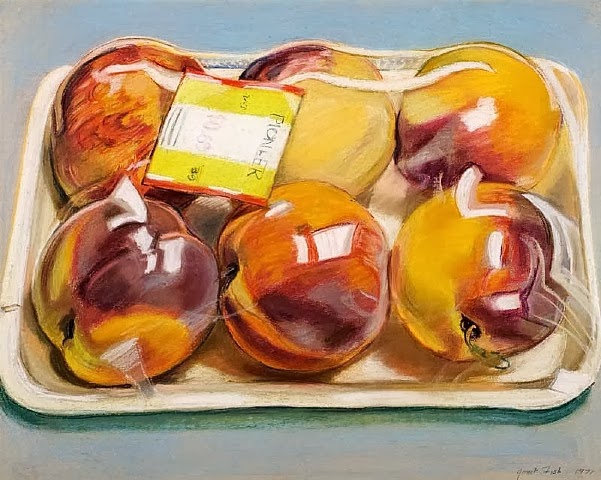

Peaches, 1973, Janet Fish

Peaches, 1973, Janet Fish

By DONALD KUSPIT January 8th, 2025

Still life paintings have been made since antiquity, and became a genre of Netherlandish painting in the 16th and 17th centuries, where they were explicitly made to represent a “slice of life.” As Pliny the Elder wrote, commenting on the paintings of “vulgar subjects” by Peiraikos, their “artistry is surpassed by only a few,” which was the polite way of saying by none. In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance still life paintings were “primarily an adjunct to Christian religious subjects and conveyed religious and allegorical meaning.” But Jacopo de’ Barbari’s Still Life with Partridge and Gauntlets, 1504, one of the earliest trompe-l’oeil still life paintings, had “minimal religious content.” Juan Sanchez Cotan’s austere still lives of fruits and vegetables, presented as sacramental objects with “singular mysticism,” do not need religious meaning to give them abstract presence, as their “geometrical clarity” indicates. From them to Giorgio Morandi’s still life paintings of bottles and vases seems like a long leap—for there are no natural objects in his still lives, as Natura Morta, 1956 makes clear, only clusters of domestic objects, bottles, empty vases, small containers—and all opaque, closed in on themselves. They smell of death, of uselessness, of meaninglessness, of mindlessness—of futility.

Janet Fish “Yellow Glass Bowl with Tangerines” Oil on canvas, 36 x 50 in. 2007

Janet Fish “Yellow Glass Bowl with Tangerines” Oil on canvas, 36 x 50 in. 2007

In startling contrast, Fish’s still lifes vibrate with light and life. One might say they are a spirited New World still life rather than a spiritless Old World still life. Indeed, Fish’s glass glistens with light, making it phenomenal, giving it a transcendental aura, a timeless freshness, while Morandi’s still lifes are the dregs of life and with that victims of time, reek of time, as Italy and the Old World does, of a society that is finished and done with, indeed, destroyed itself. But to limit Fish’s still lifes to their Americanness is to sell them short, to betray and undermine their “profound perception,” their “intellectual side,” their “willed seeing,” the “scrupulousness that makes for classicism,” which are the ways Paul Valery characterized the art of Degas.(1) But what makes Fish’s still lifes perceptually special is what Maurice Merleau-Ponty calls “the demand for awareness” they put on us, the “attentiveness and wonder” they arouse, and with that places in abeyance “the assertions arising out of the natural attitude.”(2) Using things that are “already there,” as Merleau-Ponty says—such as Fish’s clear glassware, empty or filled with such liquids as water, liquor, or vinegar, or her plastic wrap—she gives us what John Cogan calls “an experience in which it is possible for us to come to the world with no knowledge or preconceptions in hand; it is the experience of astonishment…in the experience of astonishment, our everyday ‘knowing,’ when compared to the knowing that we experience in astonishment, is shown up as a pale epistemological imposter.”(3) Fish’s still lives—filled with fresh light, spontaneously given and moving swiftly, sometimes convulsively, certainly compulsively, but always with a cosmic completeness and force—are in effect and principle what James Joyce called an epiphany: “a sudden spiritual manifestation, whether from some object, scene, or event, or memorable phase of the mind—the manifestation being out of proportion to the significance or strictly logical relevance of whatever produced it.”

Janet Fish, “Majorska Vodka” Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in. 1976

Janet Fish, “Majorska Vodka” Oil on canvas, 60 x 48 in. 1976

What Joyce calls an “epiphany” is what the philosopher Husserl calls an “epoche”—"the name for whatever method we use to free ourselves from captivity,” what Husserl calls “captivation in acceptedness.” As Cogan writes, “we live our lives in an unquestioning sort of way by being wholly taken up in the unbroken belief-performance of our customary life in the world. The epoche is the name for whatever method we use to free ourselves from the captivity….The most important point to be made in reference to the phenomenological reduction is that It is a meditative technique.” One might say that Fish frees her objects from their usefulness to reveal—for Fish’s works are revelations—their essence, and with that their undeniable presence, their irreducible givenness, apar t from whatever usefulness they may have. Liberated from banality, they radiate with light, become transcendental, that is, transcend themselves, “goes beyond the regular physical realm” to reveal their essence. Fish probably chose to paint glass because it seems to transcend its materiality—dematerialize—when light passes through it, ”spiritualizing” it. It is worth noting that epoche is an ancient Greek term for “cessation,” which came to mean, in the words of the philosopher Sextus Empiricus, “a state of the intellect in which we neither affirm nor deny anything” in order to induce a state of ataraxia, freedom from worry and anxiety. Fish’s painting is a healthy alternative to all the Sturm und Drang—anxiety-ridden—painting from German figurative expressionism to American abstract expressionism, and as such a rare beacon of health in modern art.

Notes

1. Paul Valery, Degas, Manet, Morisot (New York: Pantheon, 1960), 55

2. Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1962), vii, xxiv

3. John Cogan, The Phenomenological Reduction, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, in passim

Donald Kuspit

Donald Kuspit is one of America’s most distinguished art critics. In 1983 he received the prestigious Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinction in Art Criticism, given by the College Art Association. In 1993 he received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Davidson College, in 1996 from the San Francisco Art Institute, and in 2007 from the New York Academy of Art. In 1997 the National Association of the Schools of Art and Design presented him with a Citation for Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts. In 1998 he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2000 he delivered the Getty Lectures at the University of Southern California. In 2005 he was the Robertson Fellow at the University of Glasgow. In 2008 he received the Tenth Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. In 2013 he received the First Annual Award for Excellence in Art Criticism from the Gabarron Foundation. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Fulbright Commission, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim Foundation, and Asian Cultural Council, among other organizations.

view all articles from this author