Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Interview with Judy Pfaff

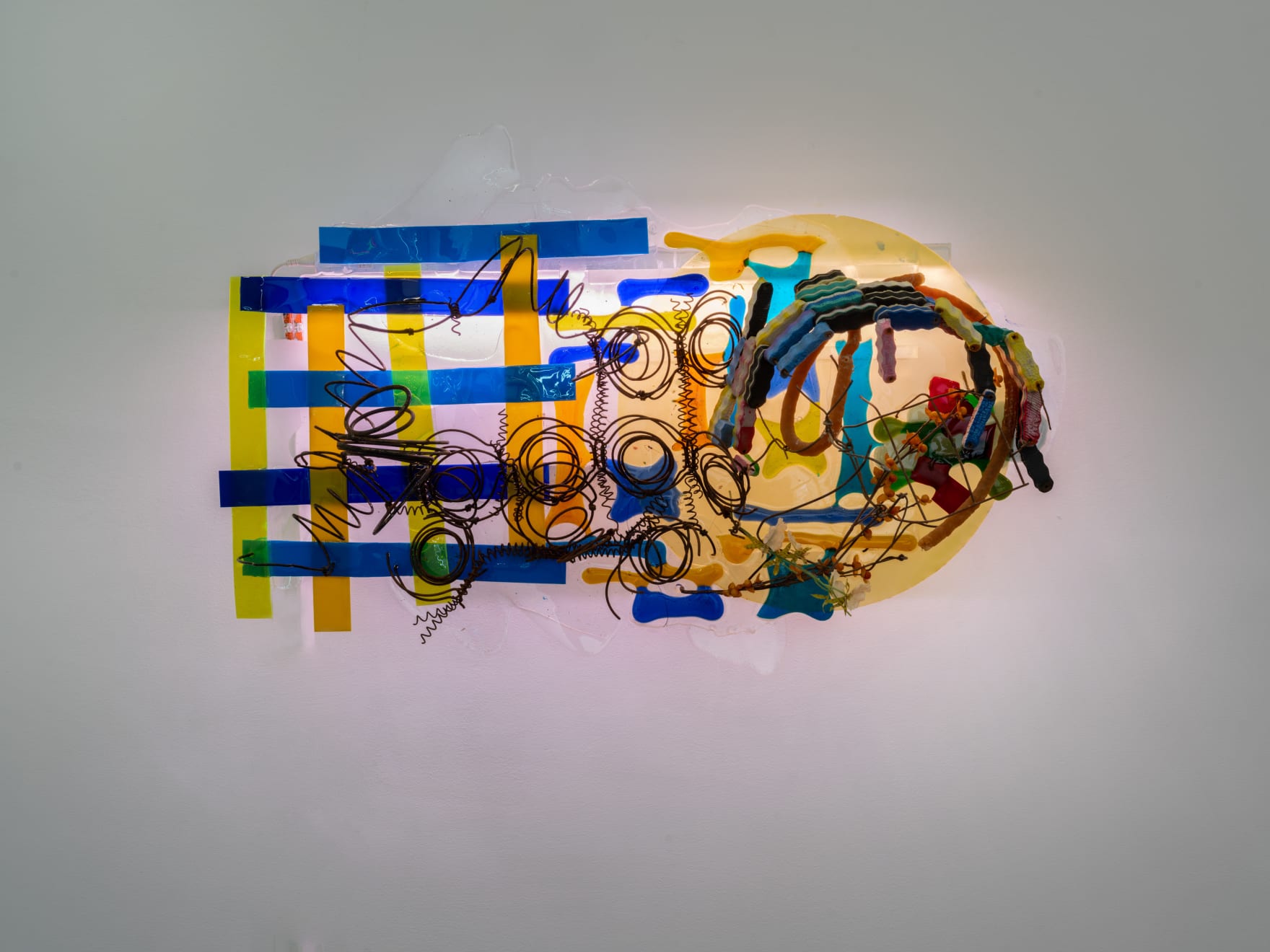

Judy Pfaff, aftermath, 2025

Judy Pfaff, aftermath, 2025

By AYSE SARIOGLU December 14, 2025

Judy Pfaff’ s work is an invitation—to feel, to move, to experience. In this exclusive conversation, she shares insights on artistic freedom, the relationship between space and light, and the ways beauty, impermanence, and materiality shape her practice.

Ayse Sarioglu : In your Light Years series, you work with neon and resin—materials that embody both light and fragility. Do you think light can have a “sculptural” body?

Judy Pfaff : Hm… yes, in a way. Neon is a strange kind of energy—different from LEDs or incandescent light. I think of it as painterly: it reflects color, creates ambient energy, and brings cheerfulness. Using neon unsupported makes it fragile, playful, almost alive. My background in painting always informs how I use color and light together.

AS : Materials often seem like “companions” in your practice. Which material has guided you most in recent years, and why?

JP : Expanded foams and epoxies have been central. Foams catalyze instantly, freezing with pigments in seconds; epoxies are slower but luminous and clear. They demand alertness, responsiveness—they almost have a mind of their own. I think of them as “cheap glass”: I can work solo or with Joe Upham for neon, but the material itself guides me, opens new ways of thinking.

AS : In your site-specific works, you prioritize intuition over planning. Is there a conscious structure behind this intuition, or is it a complete surrender?

JP : There’s initial planning, of course, but often it feels dead once I arrive. I let the space guide me—it has its own spirit. Exhaustion brings clarity; at that point, I feel like I’m back in my studio. The real work happens when you stop thinking and start listening.

AS : The interplay between industrial materials and natural forms in your work can be read ecologically. Do you see yourself from an eco-feminist perspective?

JP : I never frame it that way consciously. But I live surrounded by nature, and I soak it in. Industrial and organic elements interact naturally—things die, things live, histories merge with objects. I love the messiness, the vitality. It’s honest and alive.

AS : In Light Years, viewers walk through neon lights into a “garden of light.” Do you consider space merely a container for your works, or is it part of the work itself?

JP : Space is absolutely part of the work. Walls, distances, sunlight—they all affect perception. The space expands, contracts, interacts with neon. Space itself becomes alive, an active partner in the experience.

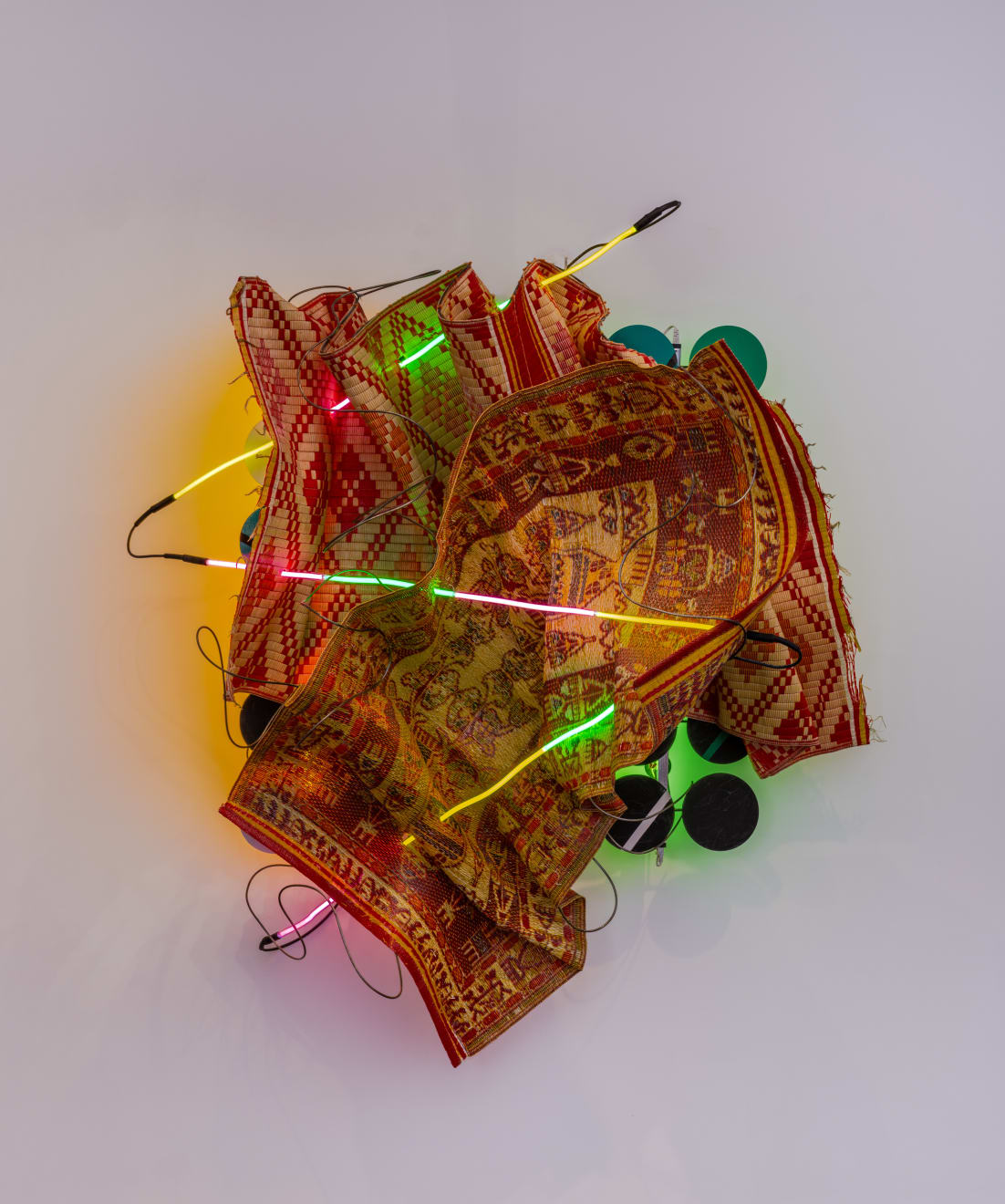

Judy Pfaff, CARPETRIGHT, 2025

Judy Pfaff, CARPETRIGHT, 2025

AS : Your works consistently invite physical interaction. What drives you to put the viewer’s body so centrally in the experience?

JP : I want generosity. If someone comes to see a show, they should leave having felt something. Movement, touch, subtle presence—they engage fully with the work. Art should give something to the viewer.

AS : You’ve mentioned accepting that installations disappear once dismantled. Do you think impermanence can offer a more honest beauty than permanence?

JP : Absolutely. In the 80s, I thought I couldn’t do installations—they were thrown away. But impermanence opens them, gives freedom. I call it “Beat the Clock” energy: quick decisions, response in the moment, alive and immediate.

AS : Is your idea of “painting in space” still relevant today? How has it evolved in the digital era?

JP : Definitely. I still work with real, tactile materials. Digital is interesting, but my practice remains hands-on. Younger artists navigate AI, video, interactive tools fluently—there’s so much to learn from them—but I’m rooted in physical exploration.

AS : The title Light Years alludes to the immeasurability of time. For you, is time primarily a physical phenomenon or an emotional experience?

JP : Both. Time is something you feel as much as you measure it. In neon, color, and space, time stretches, compresses—it becomes a sensation, not just a number.

AS : The light in your works seems to embody both life force and disappearance. Do you see light in art as a tool of hope or an illusion?

JP : Light carries energy, vitality, presence. But it’s fleeting, ephemeral. It’s hope, yes—but it also reminds you of impermanence. That tension is what excites me.

AS : There is a sense of constant transformation in your work. Is this motion a personal escape, or an existential search?

JP : A little of both. It’s about exploration, learning, evolving. Materials, space, light—they are always moving, always surprising. I respond, adapt, and let it lead me.

AS : In works like Corona de Espinhos, nature and the sacred intertwine. Is nature now primarily a metaphor for humans, or still a tangible, livable space?

JP : Nature remains tangible. In Brazil, for instance, I engaged with actual trees, landscapes, and sacred architecture. Nature informs structure, light, and space—it’s alive, not just a symbol.

AS : As a female artist, do you see your act of transforming space as political?

JP : Being a woman in art is inherently political at times, but I never started from that angle. I aimed for strength, generosity, openness. My work may have challenged male colleagues simply by being loose, colorful, playful—yet powerful.

AS : While aestheticizing the chaos of nature, do you worry about “too much beauty”? Is beauty a trap or a strategy?

JP : I used to avoid beauty, thinking it superficial. Now I accept it—if it has content. Beauty isn’t empty; it can coexist with message, tension, and honesty. It’s a strategy, but also joy.

AS : From the 1970s to today, how has your understanding of artistic freedom evolved?

JP : Back then, you picked a lane: figurative or abstract. Personal life, identity, even emotion was off-limits. Today, young artists explore freely. They create without permission—it’s liberating and inspiring.

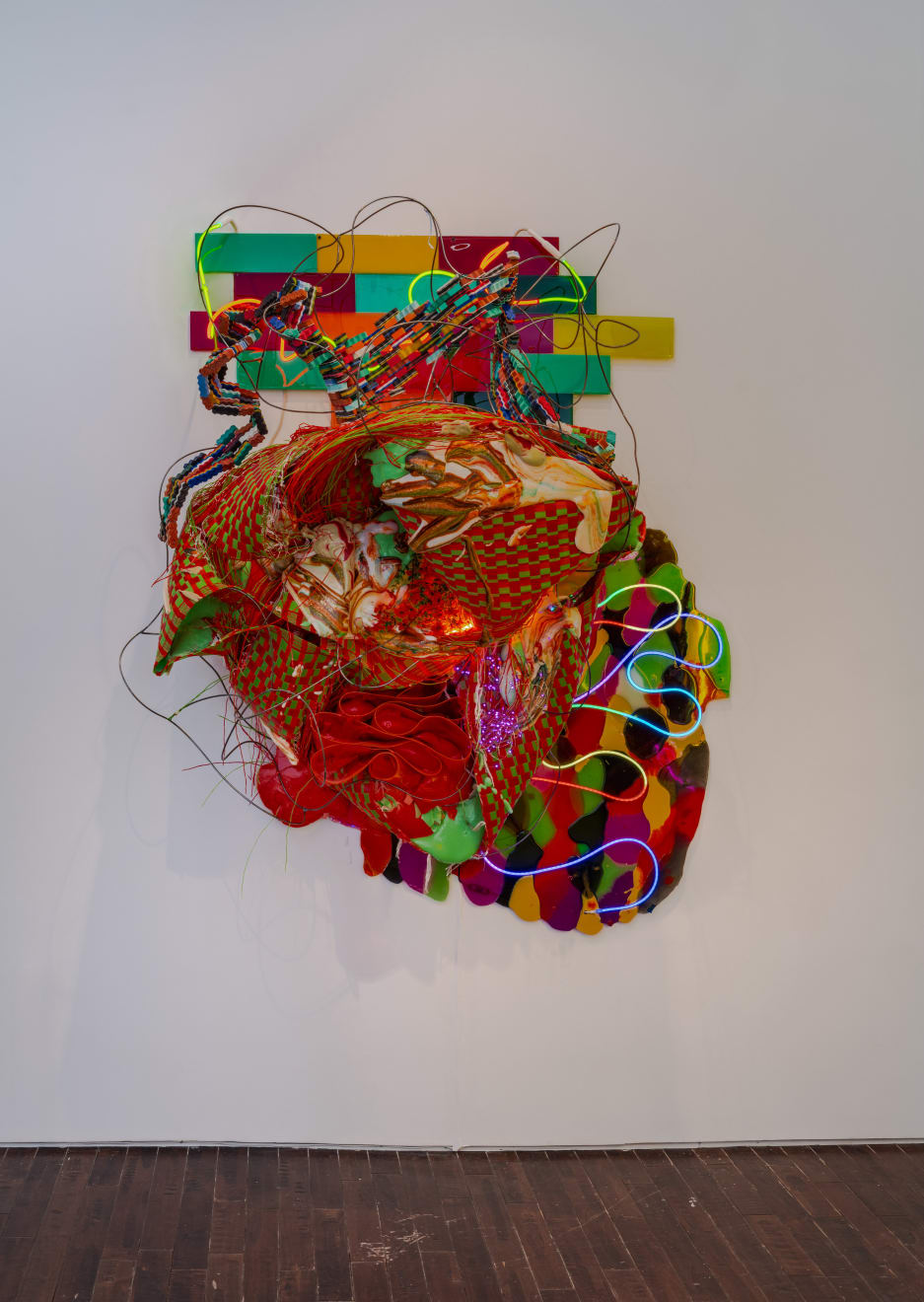

Judy Pfaff, Rood en Groen (voor Sjorsje), 2025

Judy Pfaff, Rood en Groen (voor Sjorsje), 2025

AS : Many young artists today work digitally. Do tactile, hand-made practices still have a place?

JP : Absolutely. Physical engagement, senses, material responsiveness—these can’t be replicated digitally. But I learn from the digital fluency of students; it keeps me alert and curious.

AS : After Light Years, what new aesthetic or technical directions inspire you?

JP : Neon fascinates me. Each gas, each tube behaves differently. It’s a new language to learn. Experimenting is thrilling—technical challenges become adventures.

AS : Over a career spanning more than fifty years, what still surprises or challenges you?

JP : Everything! Materials, students, spaces, light—they constantly teach me something new. You can teach an old dog new tricks, and I embrace it wholeheartedly.

AS : Your works carry intense energy but also a sense of melancholy. Is this paradox a reflection of your life philosophy?

JP : Life itself is contradictory. Energy, joy, melancholy—they coexist. Art reflects that truth.

AS : If your art were a music genre, which would it be—and why?

JP : A mix: hip hop, jazz, salsa, folk… energetic, layered, unpredictable. Just like the work.

AS : How would you like your art to be remembered—in legacy or as a feeling?

JP : As a form of feeling. Not sentimental, but precise, intelligent, embodied feeling. That’s what I hope to leave behind.

Key Takeaways:

Space is active and alive; it interacts with materials, light, and viewers.

Generosity matters: art should give something to those who encounter it.

Impermanence breeds honesty, freedom, and immediacy.

Beauty and meaning can coexist; joy is valid in art.

Artistic freedom has expanded, offering unprecedented liberty to new generations.

Materials—neon, resin, foam—remain central to exploration, discovery, and delight. WM

Ayse Sarioglu

Ayse Sarioglu-Guest is a senior Turkish media executive, writer, and art critic based in Istanbul and New York. With over 25 years of executive experience in Turkey’s leading media organizations, including Sabah and ATV Group, she has held key leadership roles overseeing national newspapers, magazines, and television networks. Sarioglu-Guest was instrumental in the launch of MTV and Nickelodeon in Turkey and led the market introduction of Eurosport. She currently contributes to Vogue Turkey and Harper’s Bazaar Turkey, focusing on contemporary art, culture, and international creative industries.

view all articles from this author