Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

Chelsea Highlights: Berry Campbell, Yossi Milo, Sean Kelly, Rosebud Contemporary, Tenri Cultural Institute, A Hug from the Art World

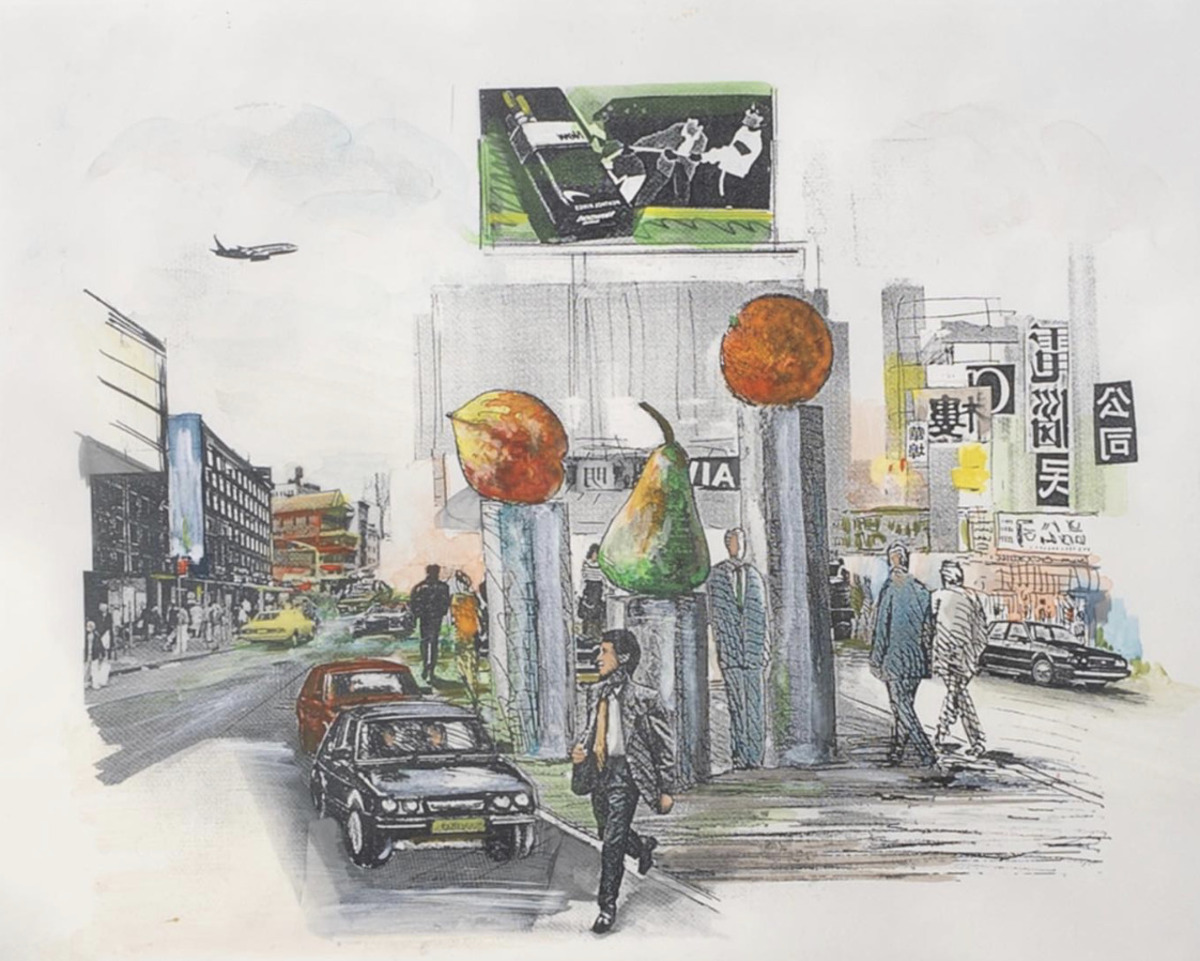

Ming Fay (Chinese, 1943 - 2025), Sprout Forest Bounty of Canal (Proposal) Monumental Fruits Sketch, 1988.

Ming Fay (Chinese, 1943 - 2025), Sprout Forest Bounty of Canal (Proposal) Monumental Fruits Sketch, 1988.

By LIAM OTERO January 4, 2026

Reverse Chinatown: Those Who Passed Through … presented by Dawn Eleven Contemporary Art Foundation (DeCA) at Tenri Cultural Institute (December 11 - December 18, 2025)

Chinatown is not just a place, for it is also an idea. Dawn Eleven Contemporary Art Foundation (DeCA), a curatorial initiative that specializes in fostering a new generation of young contemporary artists, recently held a week-long exhibition that considered what “Chinatown”, as an idea rather than as a place, signified to younger artists of Chinese descent.

Fangshi Qi (Diego) & Guangyuan Xing (Sam), The Weight of Leaving, 2025.

Fangshi Qi (Diego) & Guangyuan Xing (Sam), The Weight of Leaving, 2025.

Because of the generational longevity of Chinatown in myriad geographical contexts, the organizers of this exhibition wisely incorporated the works of an older, more established Chinese artist into its narrative to create a more enriched dialogue. Ming Fay (Chinese, 1943 - 2025), who sadly passed away early last year, was a major figure in public art renowned for his enlarged, environmentally encompassing fruit sculptures. Sketches for unrealized public art commissions in New York’s Chinatown and nearby subway stops were presented, each containing colorfully buoyant drawings of gigantic pears, cherries, oranges, and other fruits on pedestals or as ceiling mobiles that alluded to culturally-specific associations, from good luck to health.

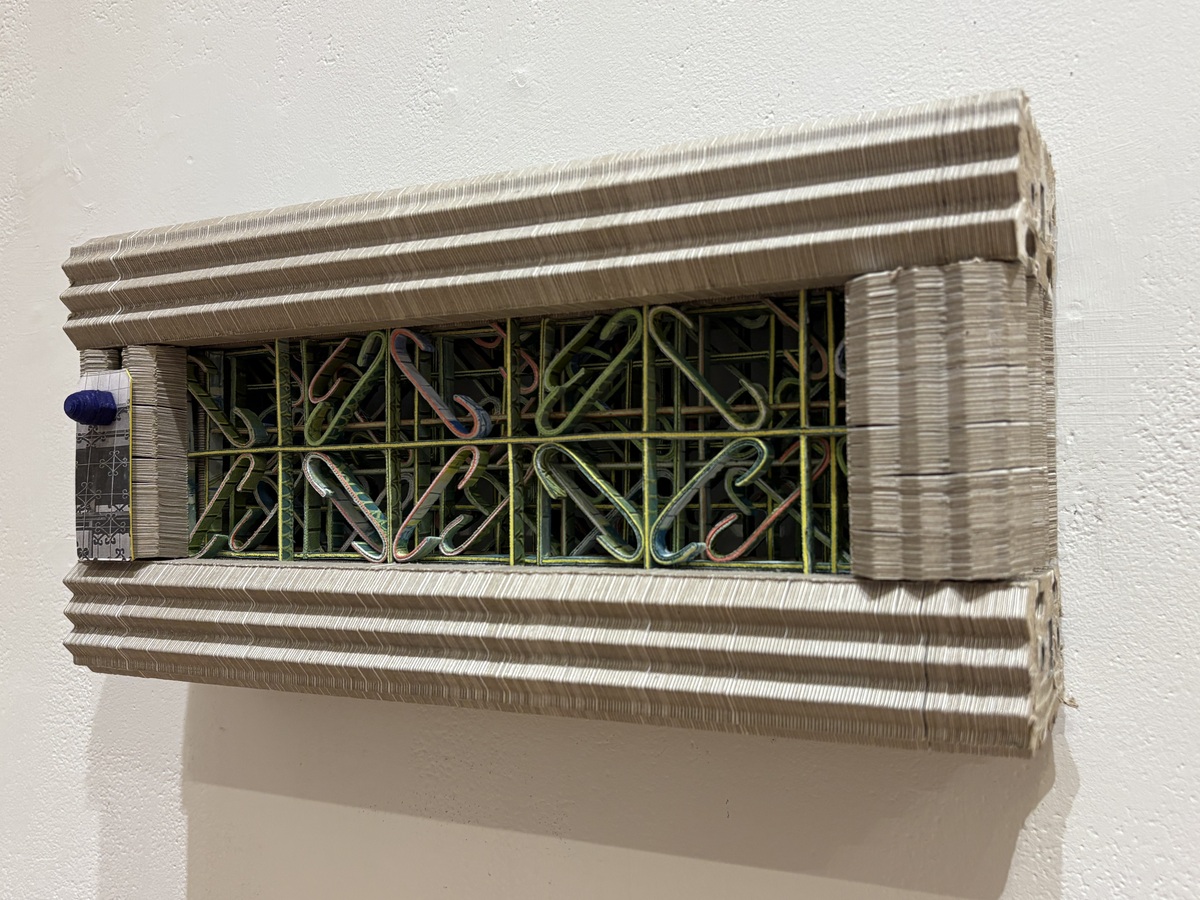

Irfan Hendrian (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1987), Chinatown Window Sample Series.

Irfan Hendrian (Chinese-Indonesian, b. 1987), Chinatown Window Sample Series.

The conceptually charged works in this exhibition shed light on personal and collective issues germane to the global Chinese experience. Irfan Hendrian’s low-relief sculptures of ornamental window gates and accompanying photobook of high-rise Indonesian apartment buildings takes a critical lens on anti-Chinese segregationist policies employed in Indonesian hostile architecture. For a more autobiographical insight, Karis Wong’s paintings appropriate distinctively Chinese aesthetics, such as the much-coveted Jingdezhen porcelain, as metaphorical imagery reflective of the transmutation of Chinese iconography and material culture in the United States.

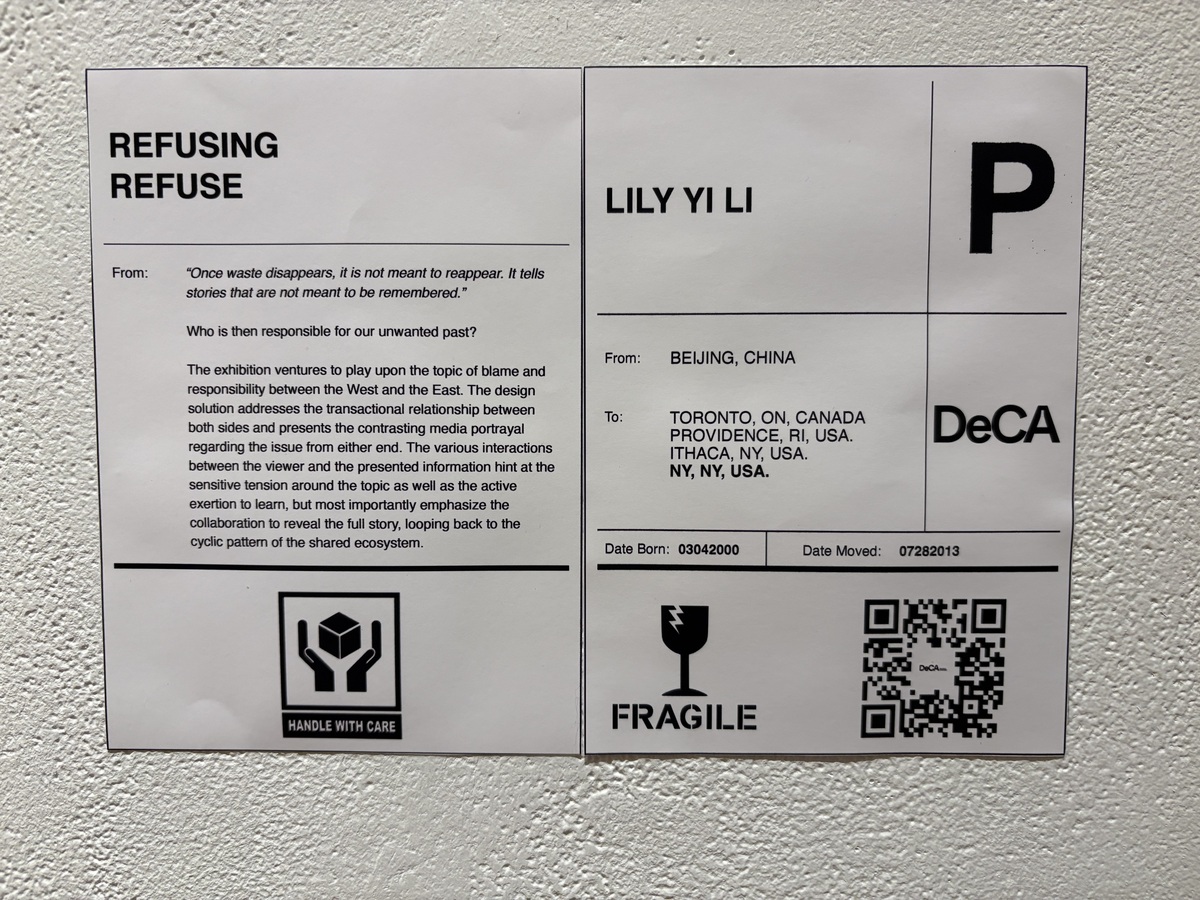

Wall label for Lilly Yi Li’s Refusing Refuse series.

Wall label for Lilly Yi Li’s Refusing Refuse series.

The wall texts that accompanied each artwork may as well have counted as artworks in themselves, for these were presented in the style of packaging labels. The artists’ birthplaces were framed as “FROM:” and followed with a “TO:” that listed each of the places in which they lived - most of whom migrated quite extensively. For an artist like Irfan Hendrian, he was originally from Ohio, but later moved to Indonesia, Singapore, New Zealand, and as of now, back to Indonesia. The wall labels are like records in tracking the migratory patterns of young artists of Chinese descent in today’s globalized world. And, of course, each of them provided sumptuous information on the artworks.

Though each of the artists come from different geographical and cultural backgrounds, Reverse Chinatown underscored the commonalities of Chinese acculturation in its international spread, from the imperialist politics of the 19th Century tea trade to the controversial dumping of foreign waste recyclables on Chinese soil.

Ibram Lassaw: From Equinox to Solstice at Berry Campbell Gallery (November 20 - December 20, 2025)

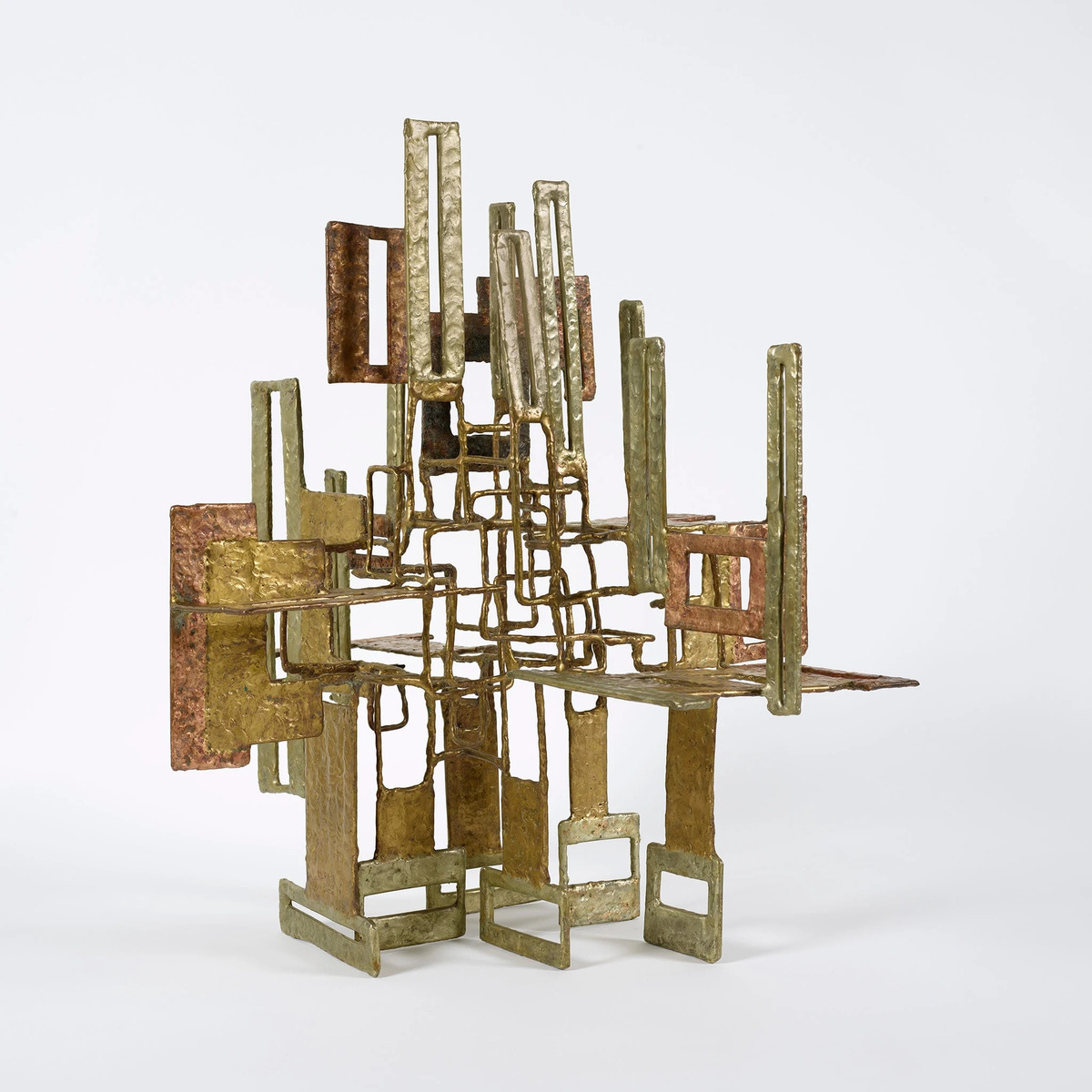

Ibram Lassaw (Egyptian-born American, 1913 - 2003), Dilmun, 1980, bronze. 23 x 25 ½ x 28 inches / 58.4 x 64.8 x 71.1 centimeters. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

It has become so refreshing to see that the narrative of Abstract Expressionism is being more vocally inclusive of sculpture considering a great many artists worked under the exact same conceptual frameworks as their painter compatriots, albeit in a language of three-dimensions. Mark di Suvero, David Smith, and Louise Nevelson are among the most popular sculptors of this style who are frequently cited, but what about Ibram Lassaw?

Forget 1950s action painting, Lassaw’s self-described “action sculpture” was the sculptor’s answer to applying rugged physicality and gestural vigor into the creation of dynamic works that elevated the standards of freestanding sculpture to new heights at a time when abstraction superseded figuration.

Installation view of Ibram Lassaw: From Equinox to Solstice at Berry Campbell Gallery. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Installation view of Ibram Lassaw: From Equinox to Solstice at Berry Campbell Gallery. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Berry Campbell Gallery’s first-ever survey exhibition of Lassaw was a well-rounded glimpse into the action sculptor’s oeuvre from the 1950s through the 1990s as seen in his welded sculptures and ink on paper images.

Ibram Lassaw (Egyptian-born, American, 1913 - 2003), Auriga, 1981, nickel-silver, phosphor-bronze steel, and brass. 34 ½ x 31 ½ x 32 inches / 87.6 x 80 x 81.3 centimeters. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Ibram Lassaw (Egyptian-born, American, 1913 - 2003), Auriga, 1981, nickel-silver, phosphor-bronze steel, and brass. 34 ½ x 31 ½ x 32 inches / 87.6 x 80 x 81.3 centimeters. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Line and shape operate hand-in-hand in Lassaw’s art as these formal elements give rise to the vertical thrust of his almost architectural configurations of intersecting planes and cage-like frameworks. Danais (1982) and Auriga (1981) were some of the most awe-inspiring of Lassaw’s work in the exhibition as these were brilliant displays of the muscularity embedded within his sculptures that ultimately energizes them with a projecting strength. These are not only reinforced by sculptures displayed on plinths or on the ground, but also those suspended from the ceiling that appear to glide like airplanes or shooting stars that cast intricate nets of shadows onto the surrounding walls.

Ibram Lassaw (Egyptian-born, American, 1913 - 2003), Thaleia’s Ladder, 1982, bronze. 13 ¾ x 15 x 15 inches / 34.9 x 38.1 centimeters. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Ibram Lassaw (Egyptian-born, American, 1913 - 2003), Thaleia’s Ladder, 1982, bronze. 13 ¾ x 15 x 15 inches / 34.9 x 38.1 centimeters. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Negative space, too, is another remarkable attribute behind Lassaw’s sculptures as these are not only works meant to be traversed as sculptures-in-the-round, but also to be observed through their open-aired structures. A work like Thaleia’s Ladder (1982) or Fields (1993) are magnificent examples because their respective rectangular slits and window-like openings are really what enables these works to breathe.

According to Berry Campbell’s online biographical entry, Lassaw “was included in many groups exhibitions of the Abstract Expressionists, but his work was not fully acknowledged as related to this movement.” It behooves me that he was not given his due as one of the greatest sculptors of that generation, but I was most pleased to see that Berry Campbell has once again remedied the canon of Modern Art History through a most convincing curatorial stratagem.

Installation view of Ibram Lassaw: From Equinox to Solstice at Berry Campbell Gallery. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Installation view of Ibram Lassaw: From Equinox to Solstice at Berry Campbell Gallery. Image courtesy of Berry Campbell Gallery.

Mariko Mori - Radiance at Sean Kelly Gallery (October 31 - December 20, 2025)

Installation view of Mariko Mori - Radiance at Sean Kelly Gallery. Photo by Jason Wyche. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Installation view of Mariko Mori - Radiance at Sean Kelly Gallery. Photo by Jason Wyche. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Radiance marked the first major solo exhibition of Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967) at Sean Kelly Gallery in 7 years since her 2018 exhibition, Invisible Dimension. The opportunity to visit this exhibition of Mori’s latest sculptures, works on paper, and installations carried much emotional weight because of the spatial evocativeness conveyed forth in her art. The high-ceilinged and angularly connected rooms of Sean Kelly Gallery (which represents Mori) wound up producing the ideal environment for Mori’s works. That sense of balance through negative space, atmospheric calm, and formal stasis actually fulfills the tenets of ma, a traditional philosophy of Japanese architecture.

Though ma is not mentioned in the press release and may not necessarily have been a curatorial motivation behind the show’s organization, this is not a far-fetched assessment given Mori’s decades-long interests in spirituality and meditation - both in her artistic process and projects.

A primoridialism pervades the works in this show as Mori deliberately undertook research into the ancient spiritual traditions and stone cultures of Japan’s Jomon (14,000 - 300 BCE) and Yayoi (300 BCE - 300 CE) periods, each possessing their own cosmological and cultural practices rooted in nature and the universe.

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Love II, 2025, Dichroic coated layered acrylic in 2 parts, Corian base. 70 ⅞ x 29 11/16 x 23 ⅜ inches / 180 x 75.4 x 59.3 centimeters, each edition of 1 with 1 AP (#1/1). Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Love II, 2025, Dichroic coated layered acrylic in 2 parts, Corian base. 70 ⅞ x 29 11/16 x 23 ⅜ inches / 180 x 75.4 x 59.3 centimeters, each edition of 1 with 1 AP (#1/1). Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Mori’s Love II (2025), a matching pair of Dichroic sculptures coated and layered in acrylic, is the artist’s contemporary retelling of one of Japan’s oldest creation myths when gods appeared as couples. According to legend, the gods Izanagi and Izanami, who were responsible for the “birth” of the thousands of islands comprising the Japanese archipelago, are represented by Mori as luminescent, crystalline monoliths of matching height and dimensions that lean towards one another. As one walks around these sculptures, the dispersions of colorful lights continually change shapes and hues, thereby evoking a sense of harmony and romance.

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Genesis III, 2022, UV cured pigment, Dibond, and aluminum. 63 ½ x 3 inches / 161.3 x 7.6 centimeters. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Genesis III, 2022, UV cured pigment, Dibond, and aluminum. 63 ½ x 3 inches / 161.3 x 7.6 centimeters. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

The tondo-shaped Unity and Genesis photo paintings that line the walls are effervescent portals leading into infinite skies or zones abounding in sparkling rays and glowing orbs. These paradisiacal windows are very much a continuation of Mori’s longstanding engagement with Pure Land Buddhism, a tenet of Mahayana Buddhism in which one partakes in the Buddhist path to enlightenment in a place free from the trials of the earthly, material world. If you’ve followed Mori’s works as I have over the years, these splendid portals are similar to the gorgeous horizon line from Mori’s much earlier work, Pure Land (1996 - 1998).

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Shrine, 2025, silk, aluminum, wood, two Dichroic coated acrylic sculptures, Corian bases. Approx. 74 13/16 x 362 3/16 x 189 inches / 190 x 920 x 480 centimeters. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Mariko Mori (Japanese, b. 1967), Shrine, 2025, silk, aluminum, wood, two Dichroic coated acrylic sculptures, Corian bases. Approx. 74 13/16 x 362 3/16 x 189 inches / 190 x 920 x 480 centimeters. Image courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

The peak moment of Mariko Mori - Radiance occurs in the final room in which a pristine, whitened enclosure resides. Silken veils demarcate the space through which one must enter with special shoe-coverings to maintain the purity of the area. Two more Dichroic acrylic sculptures line the space while emitting dazzling lights in an array of vibrant hues. That concept of ma functions so beautifully here as the vastness of the enclosure’s space, which bears similarities to a Zen Buddhist garden, punctuated by the heavenly presence of Mori’s resplendent sculptures encourages one to sit down, lose yourself, and meditate, with absolutely no external distractions present.

The architectural layout of Sean Kelly Gallery is one-way, which means that after finishing in the shrine, one has to retrace their steps back from whence they came. I am no expert in Buddhism, but what I do know is that if you surrender yourself for a few minutes to attaining even the slightest iota of inner harmony, you will come away a changed person for the better. Thus, not only are you interiorally enhanced, but Mori’s art, too, attains a higher degree of inner distinction. Again, the essence of ma - implemented either consciously or unconsciously - was the quiet actor that brought each of Mori’s works and the exhibition as a whole to a kind of nirvana-level visiting experience.

Thomas Grünfeld: Misfits at A Hug from the Art World (November 6 - December 20, 2025)

Installation view of Thomas Grünfeld: Misfits at A Hug from the Art World.

Installation view of Thomas Grünfeld: Misfits at A Hug from the Art World.

One of the craziest shows of 2025 took place at A Hug from the Art World, itself one of the great institutions where humor and eccentricity have a home (also, one of the most architecturally impressive galleries in the neighborhood). “Umm … what is going on here?” or “What the hell!?” were the average responses I received when I shared my photos of a cat with the body of a rabbit to one of my Instagram stories. This bizarre splicing of animals, sometimes those of divergent classes or species, are the cast of German artist Thomas Grünfeld’s series, Misfits.

Adam Cohen, the founder of A Hug from the Art World, told me that he first encountered Grünfeld’s strange taxidermied animal hybrids in the group exhibition, Young German Artists 2, at London’s famed Saatchi Gallery in 1997. Almost three decades on, Grünfeld’s Misfits remained firmly ingrained in the mind of Cohen who decided to make the call to stage an exhibition of these sculptures.

Thomas Grünfeld (German, b. 1956), Cow / Bull Mastiff, 2013, taxidermy. 29.5 x 35.4 x 13.8 inches / 75 x 90 x 35 centimeters.

Thomas Grünfeld (German, b. 1956), Cow / Bull Mastiff, 2013, taxidermy. 29.5 x 35.4 x 13.8 inches / 75 x 90 x 35 centimeters.

A Hug from the Art World, which conveys the appearance of a modern townhouse as opposed to the standard white cube gallery, felt like the best venue in all of New York for this exhibition to occur. London in the 1990s was the urban gateway to virtually every progressive, pioneering, and controversial development made in international Contemporary Art. Cohen, who is essentially of the same generation as some of the younger members of the YBAs (Young British Artists), was naturally the right cultural steward for introducing Grünfeld’s Misfits to new audiences in the heart of the New York art scene.

Thomas Grünfeld (German, b. 1956), Jack Russell Terrier / Sheep, 2018, taxidermy. 19.7 x 21.7 x 7.9 inches / 50 x 55 x 20 centimeters. Image courtesy of A Hug from the Art World.

Thomas Grünfeld (German, b. 1956), Jack Russell Terrier / Sheep, 2018, taxidermy. 19.7 x 21.7 x 7.9 inches / 50 x 55 x 20 centimeters. Image courtesy of A Hug from the Art World.

People often talk about the initial shock value of Damien Hirst’s well-known formaldehyde tiger shark installation, which owes to the imposing scale and frozen terror of this predator of the seas. I think the surprise element of Grünfeld’s Misfits comes through in their diminutive scale as the animals he worked with here are either household pets or smaller livestock. Their freestanding presence throughout the gallery, much like the pets you have at home, feel eerily alive, but yet, appealing at the same time as they do not exude a feeling of danger like Hirst’s shark.

I appreciate an efficacious mindfuck as these sculptures are the type of work to invite a glance, maybe a lookaway, and then an immediate snap around upon the realization that all is not as it seems. Cat / Rabbit (2025) or Fox / Cat (2025) might not be as apparent in the initial glance as these almost - emphasis, almost - could pass for some rare, little heard of species … until you lay your eyes on the Rooster / Fawn (2025) or Jack Russell Terrier / Sheep (2018)!

Installation view of Thomas Grünfeld: Misfits at A Hug from the Art World.

Installation view of Thomas Grünfeld: Misfits at A Hug from the Art World.

Grünfeld’s Misfits came about in 1988, two years after the radioactive disaster at Chernobyl in which one of the many long-term consequences of its nuclear meltdown resulted in the infection and mutation of native flora and fauna. Could these Misfits be seen as the imagined hybrids of what happens when the follies of manmade scientific progress has run afoul? Grünfeld’s sculptures are not lifelike representations of animals, for they are really repurposed animal parts that have been stitched together through the art of taxidermy. This transformation of animal matter into an all-together new creature is one of the great shake-ups to Contemporary Art and it continues to maintain a potency through its anti-Animal Kingdom, species-bending, faux-genetic splicing.

Zoe Walsh: Night Fields at Yossi Milo Gallery (on view through January 11, 2026)

Installation view of Zoe Walsh: Night Fields at Yossi Milo Gallery. Photo by Olympia Shannon.

Installation view of Zoe Walsh: Night Fields at Yossi Milo Gallery. Photo by Olympia Shannon.

I am dead certain the average reader on here will agree with me that one cannot truly appreciate a physical work of art if it is solely seen through either a digital or print reproduction. Brushstrokes are lost, collaged textures have flattened, everything is blended into one mass. Presuming you are a devoted gallery goer like me, this is my plea to you to visit Zoe Walsh’s show at Yossi Milo, for any digital reproduction of their work does not do justice in visually conveying the technical mastery behind Walsh's multifaceted paintings.

Yossi Milo’s press release gives an extremely thorough breakdown of Walsh’s creative process, but in sum, it is quite a dedicatedly laborious one entailing 3D modeling, elaborately staged photographic tableaux, research-based sourcing of archival materials, multiple layers of silkscreening, and painting.

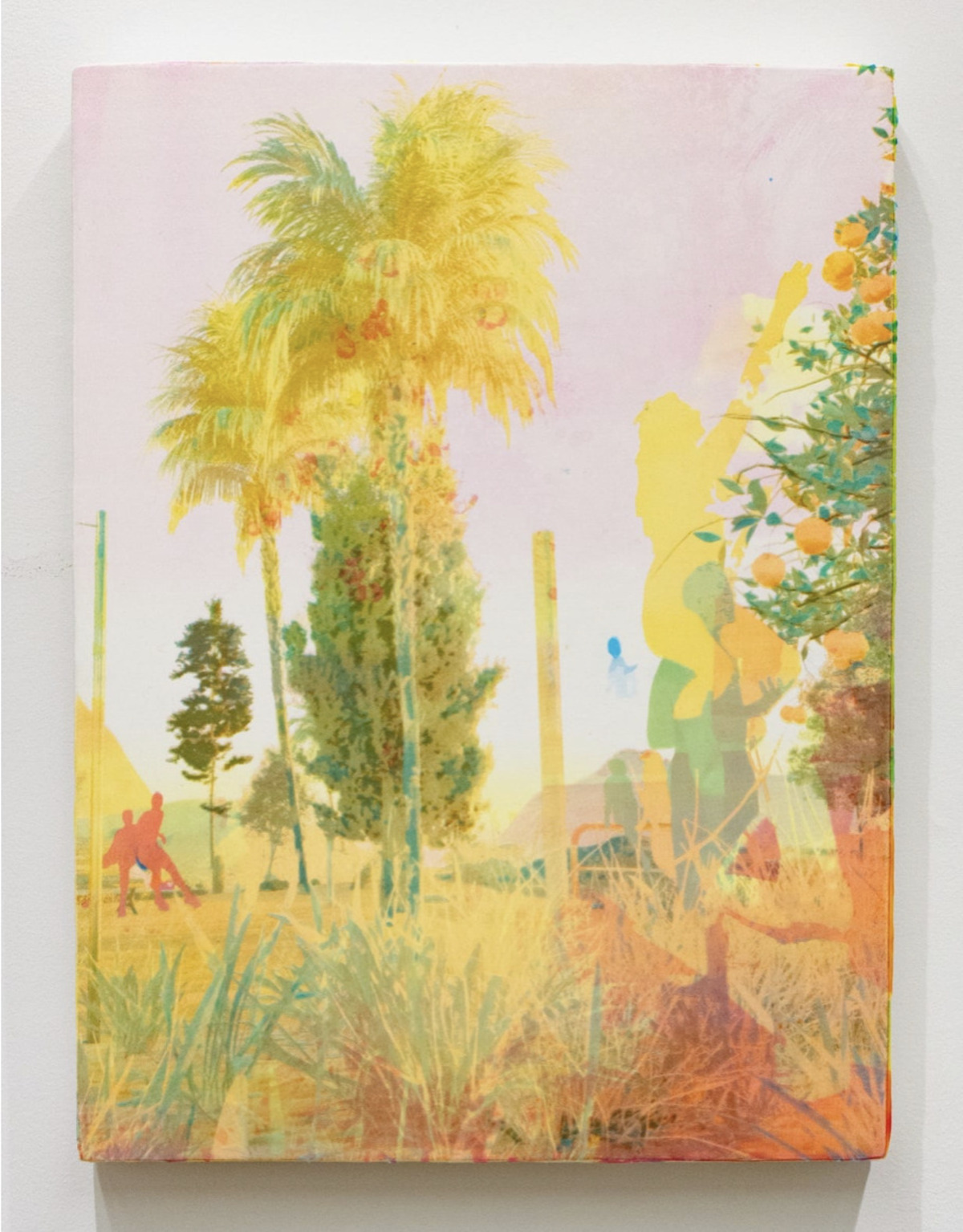

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington D.C.), Stillness Of, 2025, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 30 x 24 x 1 3/4 inches (76.2 x 61 x 4.4 cm.). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington D.C.), Stillness Of, 2025, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 30 x 24 x 1 3/4 inches (76.2 x 61 x 4.4 cm.). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Queer visibility is an important theme that permeates Walsh’s images as they incorporate film stills from the works of the gay, Los Angeles-based filmmaker Pat Rocco (American, 1934 - 2018) in tandem with photographs taken by Walsh in collaboration with their spouse Isabel Osgood-Roach and friends.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), In the Dust of Summer, 2023, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 72 x 90 inches (189 x 228.5 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), In the Dust of Summer, 2023, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 72 x 90 inches (189 x 228.5 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

The fruits of Walsh’s creative labors amounts to a spectrally bounteous collection of images brimming with an impassioned vitality. Nude silhouettes of youthful figures gather and relax in the rays of idealized nature, represented in overlapping transparent layers in tonally varied shades of non-localized colors. It’s important to keep changing your vantage points when observing Walsh’s paintings because this interaction will not only make you more attuned to the fastidiousness of their detailing, but also to experience an illusory movement of the subjects such as the swaying of trees or the rustle of bushes.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), Arriving, 2024, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 40 x 30 inches (101.5 x 76 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), Arriving, 2024, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 40 x 30 inches (101.5 x 76 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

When you study the history of Western painting, scenes of amorous display often centralize a heterosexual gaze enmeshed within the aesthetic strictures of the academic landscape genre. Walsh went ahead and transformed this into a show of not only queer visibility, but queer reclamation. The figures are situated in a plane of reverie denoted by the tranquilly sensuous atmosphere overflowing in prismatic illuminations. Their bodily gestures, too, reveal a sense of liberation - a lone figure with a leg bent like an explorer as they gaze off into the distance, a man and a woman whose bodies affectionately coalesce within the branches of a tree, and multiple scenes of reposed daydreaming.

An impressive aspect to Walsh’s paintings is that this emotive power is consistent irrespective of the scale of works as their compositions in the exhibition range from conventional painterly dimensions (around 30 x 24 inches) to a nearly wall-to-wall work comprising three canvas-wrapped panels.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), Study A for in Our Eyes, On Our Tongues, 2023, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 16 x 12 inches (40.5 x 30.5 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Zoe Walsh (b. 1989, Washington, D.C.), Study A for in Our Eyes, On Our Tongues, 2023, acrylic on canvas-wrapped panel. 16 x 12 inches (40.5 x 30.5 cm). Image courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery.

Pleasure as a form of agency for an individual and an entire community was one of the lasting takeaways I reaped from both viewing Walsh’s works and reading the stories behind their inception from the show’s beautifully composed press release. The settings for these images are deeply Los Angeles-rooted - the parkland scenes deriving from Griffith and Elysian, which is where many of Rocco’s works were filmed. Walsh’s sites of nature as metaphors for liberation and open expression made me think of the ways in which this idea can be seen as an evolution from some notable predecessors, namely 18th Century Rococo fête galante paintings and Henri Matisse’s recurrent cavorting nude figures. Much like these earlier art historical examples, Walsh’s resplendent works accomplish similar sensations, but their work is totally in a league of its own on account of the nuance brought to its technical and narrative weaves.

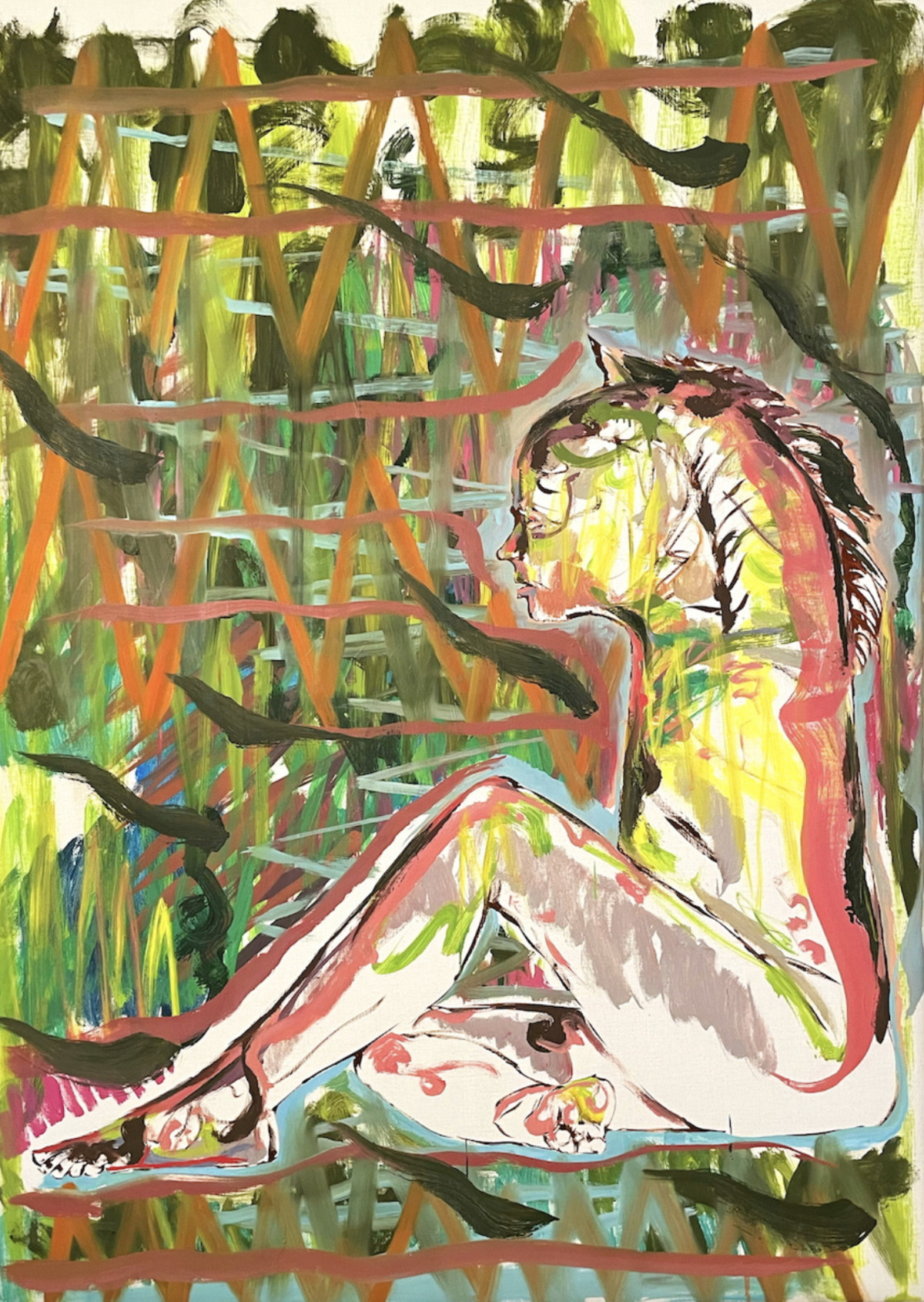

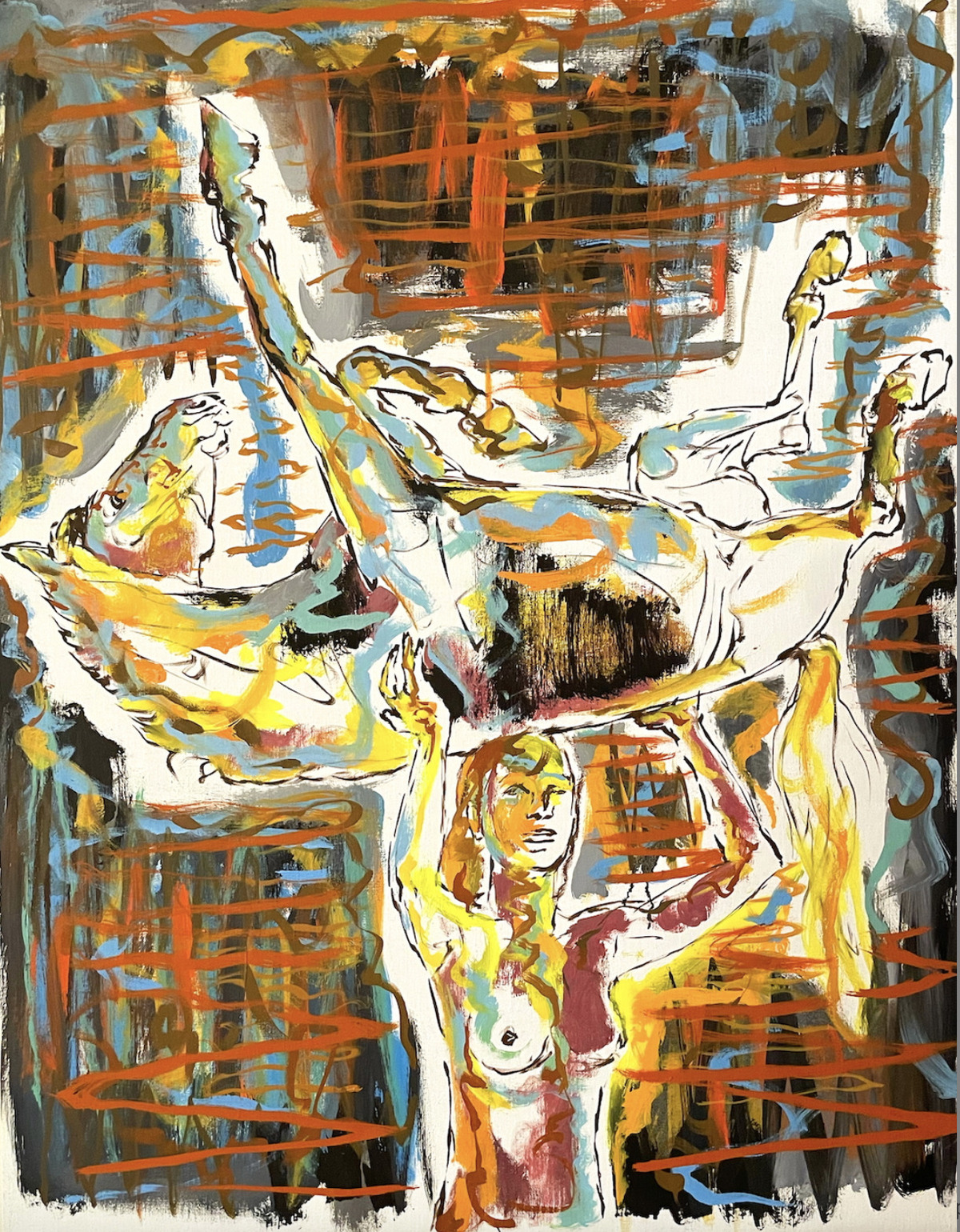

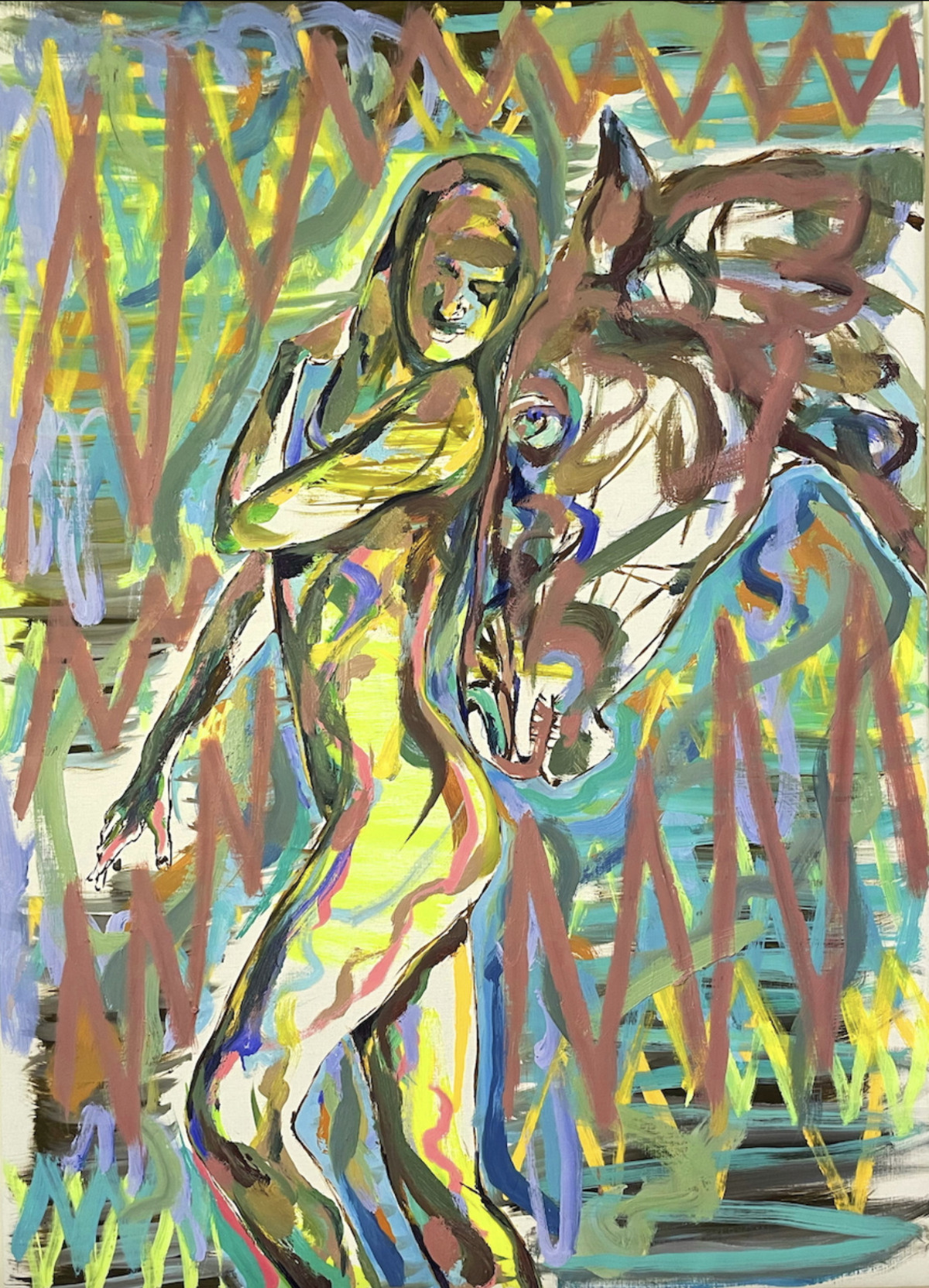

Ebenezer Singh: Horse Tamer at Rosebud Contemporary (on view through January 30, 2026)

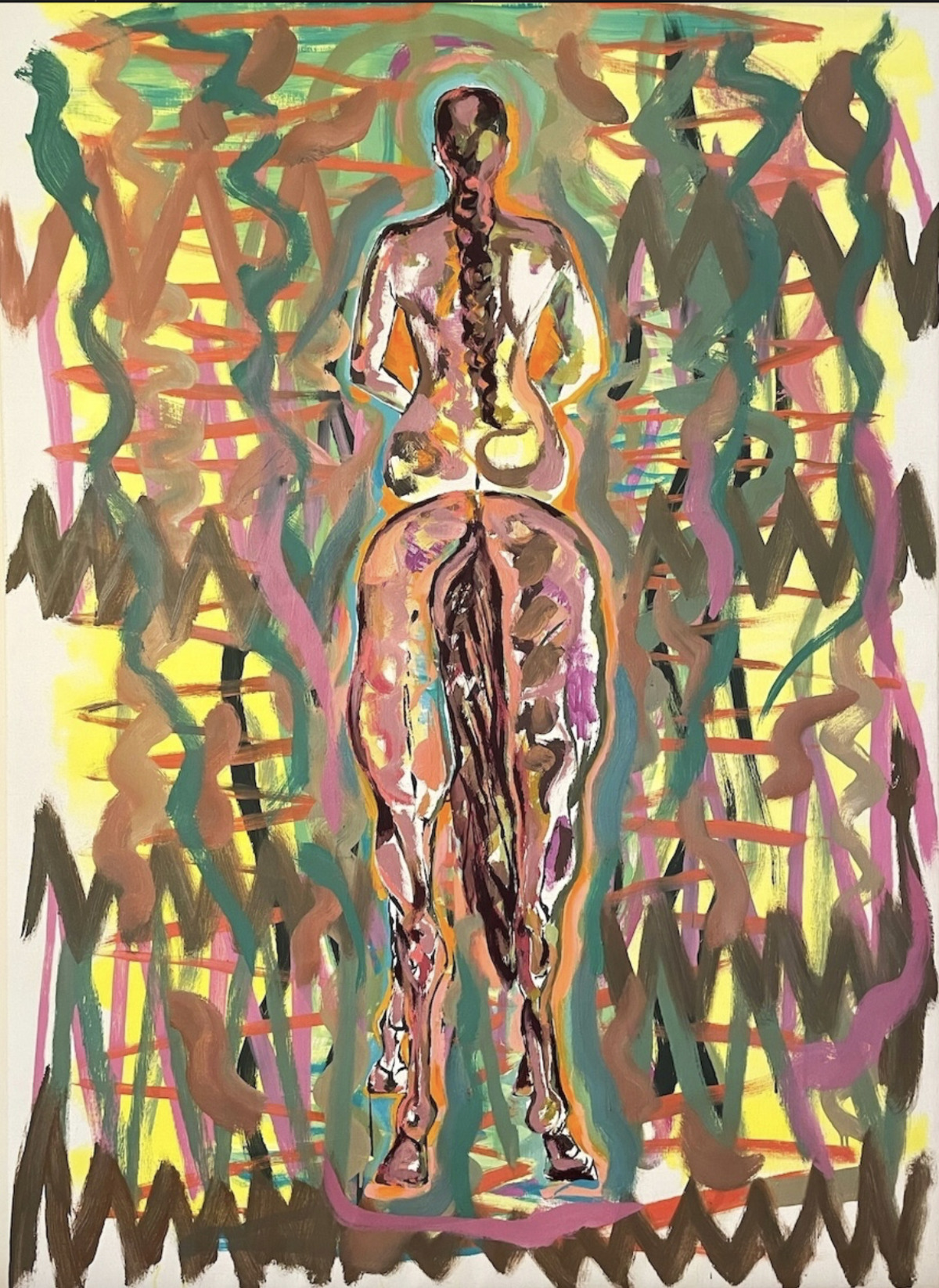

Ebenezer Singh, Horse Neck, 2025, oil on linen. 66 x 48 in (167.6 x 121.9 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

Ebenezer Singh, Horse Neck, 2025, oil on linen. 66 x 48 in (167.6 x 121.9 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

Surrealism is a term that has become a little overinflated and tossed around too much these days, to the point where an artist whose style is not overtly Photorealistic or just plain realistic is deemed “surreal”. Ebenezer Singh, on the other hand, is one of those artists who genuinely fits into the camp of “capital S” Surrealism, precisely that kind from the days of Breton and Dali but also with a side of Odilon Redon’s Symbolist connections.

A major reason why Singh’s work adheres to that classic Surrealist ethos comes down to the infusion of metaphorical imagery as depicted in an ephemeral zone that teeters on the threshold of dream, reality, or the subconscious. As suggested in the exhibition’s title, it is the horse and its tamer who appear as Singh’s allegorical protagonists.

Ebenezer Singh, Crossing the River, 2025, oil on linen. 36 x 28 in (91.4 x 71.1 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

Ebenezer Singh, Crossing the River, 2025, oil on linen. 36 x 28 in (91.4 x 71.1 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

As if conjuring a thicket of woodland or jungle foliage, Singh’s paintings are filled end-to-end, corner-to-corner with a dizzying veneer of thickly applied lines suggestive of some kind of indeterminate natural landscape. Sutured within these hyper-detailed scenes is the figure of a horse and a nude woman. The actions between them vary: in one instance she is astride the horse like the legend of the Anglo-Saxon figure Lady Godiva; in another, the horse’s head nestles against her nude back; or, in a show of Atlantean strength, she carries the horse over her body.

Ebenezer Singh, Whisperer, 2025, oil on linen. 36 x 28 in (91.4 x 71.1 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

Ebenezer Singh, Whisperer, 2025, oil on linen. 36 x 28 in (91.4 x 71.1 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

“Taming a horse is an art” is a statement that opens one of the paragraphs in the press release, which feels like something the historic horse painter George Stubbs would have uttered. For the context of this exhibition, horse taming is expressed as a metaphor, a reflection on one’s interiority in dealing with the “invisible horses … those that live within us.” I interpret the invisible horse in a few ways: our conscience, soul, yin / yang, moral compass, or mental health, maybe even all the above (and more).

Ebenezer Singh, Horse Tamer, 2025, oil on linen. 66 x 48 in (167.6 x 121.9 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

Ebenezer Singh, Horse Tamer, 2025, oil on linen. 66 x 48 in (167.6 x 121.9 cm). Image courtesy of Rosebud Contemporary.

The horse is an animal that has been domesticated across world cultures for millennia, but even then, that doesn’t mean that horses are 100% docile or independent, for the act of taming is needed to create balance. So, too, does Singh’s paintings each capture a different stage of taming that occurs within ourselves, which could be anything from staving off an addictive moment, fighting off self-doubt, or controlling one’s intrusive thoughts. WM