Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

Exhibition Review - "Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" at 1969 Gallery

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

BY SERENA HANZHI WANG, Sep 16th, 2025

Group shows used to announce a style, a school, sometimes even a revolution. But the show I’m seeing now accepts what everyone already knows—that in 2025, contradiction is the only common ground.

At 1969 Gallery, where splintering is allowed and unity never enforced, Parallax: Traversing Image and Text doubles down: contradiction is the feed, the default setting. Curated by Pasha Smelyantsev and Hengzhi Huang Yang, the exhibition brings together a dozen young New York City artists, each working within a niche so specific it risks collapsing inward. Yet together they sketch the truth of now. That truth is less about clinging to a fake common ground than about recognizing the divergence we already inherit. Even artists living on the same block can inhabit incompatible symbolic systems, where Art about Jesus and Justin Bieber can coexist in one room without apology.

Seen against the backdrop of fifty years ago—when academies and city cliques still sealed the art world into a narrow class, such simultaneity, and this range of voices and racial diversity, would have been unthinkable.

Childhood

Tao Lin’s Mandala 82 (2025) looks like a genuine child’s cosmic-travel notebook, pastel doodles and cartoon eyes drifting across a pencil grid. Arrows and circled numbers set up a game, with “Instructions” telling us to follow, count, and finally flip the page 180 degrees. Yet the order is not all. Lin stacks image upon image, layering a visual universe inspired by grids and numbers but ultimately fluid, centerless, and unstable. Even the literal word IGNORE has a section, a reminder that the rules Lin set-up here are provisional at best. I think the game is not just for the sake of being playful but methodological: childhood as a system to understand ourselves will begin with structure only to dissolve into freedom.

Tao Lin, Mandala 82, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Tao Lin, Mandala 82, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Noa Sigal approaches the same portal with a pale blue notebook disguised as painting. Her I Look For You When I’m Half Asleep (2025) reads like a teenage diary: “I heard that Maitreya is coming in code / born of the zeros and ones that we saved…,” the line whispers, blending an almost biblical prophecy (Maitreya, the future Buddha) but in cyber punk realm. and In a few lines the poem ends up with an ordinary fear of leaving the stove on. I really love how free the mind can be although a lot of the time we don’t allow it.

Noa Sigal, I Look For You When I'm Half Asleep, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Noa Sigal, I Look For You When I'm Half Asleep, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Jesus Loves You

Dylan Teaford’s art could be mistaken for a fragment from a medieval church. It’s a flat hydrostone relief, as gray as old cement, etched with saints’ silhouettes that look as if time were their only enemy. Teaford has a whole series of these pseudo-artifacts—plaster panels with titles like Destroyer, Kiss Relief, or the telling Symbol Fatigue No. 2. But when I stop at In the Hollow of My Hand (2025), up close I notice a four-leaf clover perched oddly at the top, long-lashed eyes hover on the surface, cartoonish things, breaking the illusion of age. simulacra of belief—faith displaced into décor. What first looked devotional suddenly feels fabricated, half kitsch. In the end, Teaford offers not belief itself but its residue: a relic perfectly suited to an era when devotion survives only as style, at once ruin and cartoon.

Dylan Teaford, In the Hollow of my Hand, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Dylan Teaford, In the Hollow of my Hand, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

If Teaford’s “relics” give off gothic spirit, Clayton Harris’s paintings brim with a Sunday-school message: Harris, a 22-year-old painter, makes text-based works that read like evangelical slogans in meme form. JESUS LOVES YOU - a jarring statement rendered in a bright orange acrylic ink. The message is clean, centered, corporate font, as if a church slogan got turned into a brand logo. Is this millennial deadpan or genuine testimony? Harris doesn’t tell us. In Parallax, myth is reanimated as symbol, longing, and meme all at once – Jesus saves, maybe, but now he does it in cheeky quotes.

Clayton Harris, She doesn’t love you anymore, but He does, 2024 © 1969 Gallery

Clayton Harris, She doesn’t love you anymore, but He does, 2024 © 1969 Gallery

Rococo Flaver Dream

Sonia Langouev’s paintings draw me into something like a Rococo daydream. In her Three Way Mirror (2025), I encounter a young girl in a swirly red dress, her figure repeated into three timid doppelgängers by the mirrors surrounding her. The whole scene is rendered in delicate, almost flat strokes, with muted grays and pinks that remind me of a faded illustration. Her dress curls with motifs inspired by the 18th century, and the rosy hues give a kind of decorative sweetness—yet something feels awkward, almost unsettling. The girl’s reflections seem to avoid meeting our eyes. Langouev is playing with voyeurism: we become observers of a private, girlish moment. The mirrors fracture her into a chorus of shy selves, suggesting fragile self-image.

Sonia Langouev, Three Way Mirror, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Sonia Langouev, Three Way Mirror, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

Before Madelyn Kellum’s paintings, I sense a nocturnal decadence, a beauty already in the act of decay. In Born to Win #2 (2025), I seem to glimpse a horse, its body entangled with wavering, curved lines. Those curves immediately remind me of a woman’s body—rounded, supple, yet stable. On the canvas they appear uncanny, almost cult-like. The figures and animals are so thin they seem nearly transparent, as if the material has stripped away a layer of skin, leaving them exposed in a stripped, desolate state. Yet despite that bleakness in the image, encountering the work in person feels utterly stunning. The surface shimmers with something like mica or neon, reminding me of a weary dawn glow—the first song after a long night.

This impression made me immediately think of Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase (1912). Kellum’s canvases also carry that sense of “process”: actions broken down and layered, images never static but always falling, always extending. Even in their extreme abstraction, I cannot shake the feeling that horses and people linger inside, flickering in and out of the misty brushwork, always in motion, always halfway through becoming.

Madelyn Kellum, Born to Win #2, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Infinite Jest

To an American audience, the word overdose can feel as dangerous as the act itself, a phantom weight that permeates Tashi Salsedo’s Overdoser (2025). The work stencils the phrase “You can’t overdose in the light of Heaven,” with overdose printed twice, the second offset and eroded like a printer’s error, merging mechanical reproduction with handmade touch. The piece is unsettling, a nihilistic joke, as if nothing can harm you once you are so called basking in the divine. Yet for our generation, it also reads low-key funny. It’s as kitsch as the kind of meme you send in a late-night break-up crisis. To me, it's an infinite jest¹ of the unbearable lightness of being².

Tashi Salsedo, Overdoser, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Tashi Salsedo, Overdoser, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Robert Falco answers with pop detritus. I can’t help but feel close to his work. Maybe it’s because I also grew up in the delirium of anime, MTV, and internet junk. His paintings look like what happens when you throw all of that onto a canvas and refuse to clean it up. Japanese drugstore face-mask packaging, the glossy skin of Korean idols—they all get layered with acrylic, enamel, airbrush, even mesh, only to be smeared, corroded, or torn apart again. In Falco’s world, merterial perfection exists only to be defaced. Together Salsedo and Falco stage a world where excess is the air we breathe,where melencolia turns comic and comedy turns bleak. In their hands, meaning unravels as a joke, looping endlessly until you can’t tell if you’re laughing or breaking.

Robert Falco, Man In The Korean Face Mask, 2023 © 1969 Gallery

Robert Falco, Man In The Korean Face Mask, 2023 © 1969 Gallery

Robert Falco, The Best of Both Worlds, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Robert Falco, The Best of Both Worlds, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Film Study

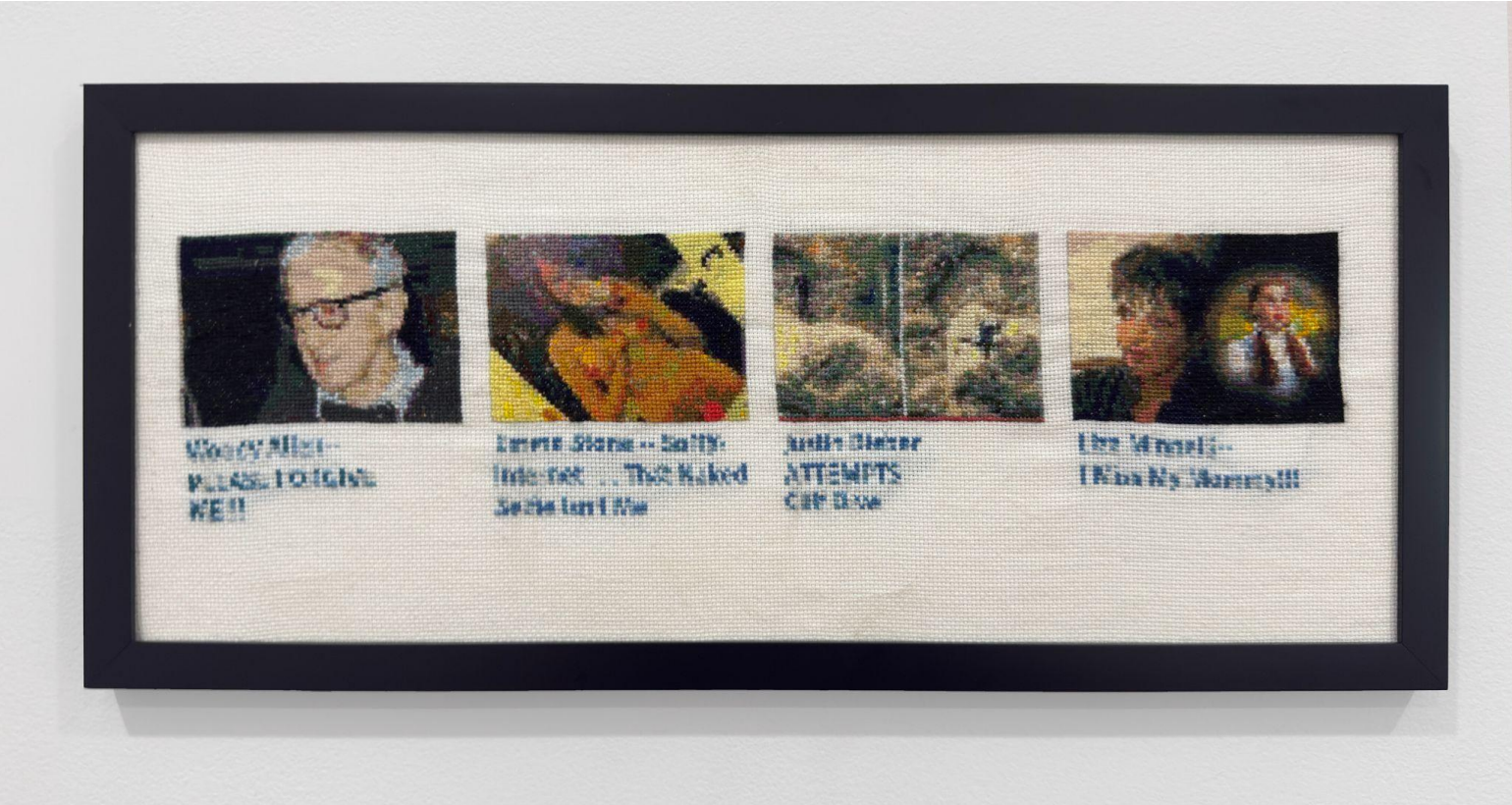

Jacob Molter’s Christmas Card #1 (2025) cross-stitches four stray media images — Woody Allen, a supposed naked selfie once claimed to be Emma Stone’s, Justin Bieber, and a “I Kiss MY Mommy!!!” The piece playfully domesticates disposable internet trash, turning clickbait and scandal into something homey. All of it is held together by the pixelated surface of embroidery — a Christmas card made of cultural garbage, presented as a precious craft.

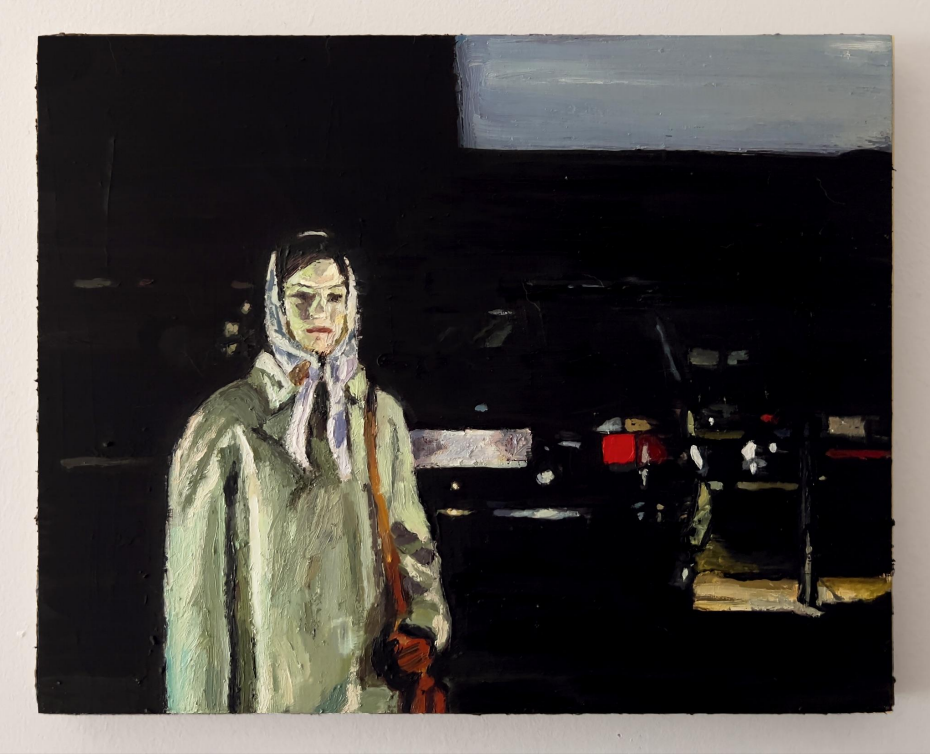

Jacob’s second painting Isabelle Huppert at the Drive-In (2024) pulls from Michael Haneke’s The Piano Teacher (2001), one of those films that never really leaves you once you’ve seen it. Isabelle Huppert plays a piano teacher who looks composed on the surface but is completely tired up inside by her mother’s control and her own twisted, repressed desires. One night she sits in her car at a drive-in theater, secretly listening to the couple in the next car having sex. She doesn’t watch; she just listens, and in that overhearing she begins to touch herself. It’s a moment where her desire leaks out sideways — through voyeurism, through shame, through the safety of not being seen.

Jacob Molter, Christmas Card #1 , 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Jacob Molter, Christmas Card #1 , 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Jacob Molter, Isabelle Huppert at the Drive-In, 2024 © 1969 Gallery

Jacob Molter, Isabelle Huppert at the Drive-In, 2024 © 1969 Gallery

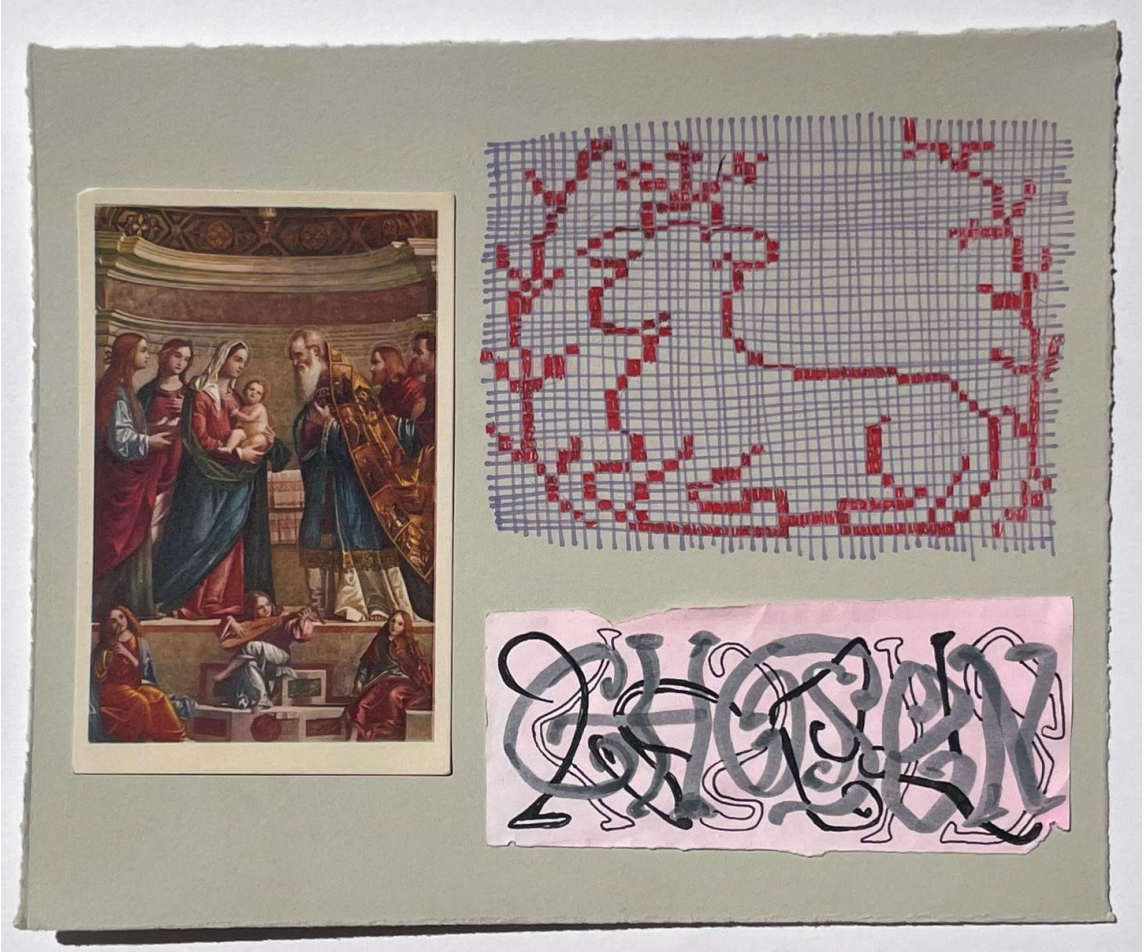

Eliana Szabó works from another archive. Instead of cinema or the internet, she pulls from historical books — holy cards of Jesus and Mary, or early images of airplanes, and arranges them into something like the matrix of a subconscious. Both Molter and Szabó show me how a massive number of images already circulate in the world — whether pop trash or devotional relics — and that if they are carefully studied and reused, new contemporary meanings will emerge.

Eliana Szabo, Chosen, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Eliana Szabo, Chosen, 2025 © 1969 Gallery

Meta Vision

In the final room of Parallax, the works fold back on themselves. Instead of just presenting images, they start to reflect on what images are, how they circulate, and how we read them. That’s why I think of this cluster as Meta Vision — pieces that turn vision itself into their subject.

Magnus von Ziegesar takes that impulse into three dimensions. His glossy plastic sculptures — in red, white, and black — at first they look like sports props or dystopian chess pieces, but a second glance turns them into something stranger: a dumbbell warped into a near-human posture, a gymnastic ribbon frozen in resin, blood-red and Möbius-shaped. Magnus, a senior at Princeton studying German, describes his practice as gesturing toward queerness, embodiment, sports, and even fidgeting. The works look sleek and playful, almost begging to be picked up, yet they ultimately refuse function. To me they echo ideas from object-oriented ontology and Deleuze’s “body without organs”: a private vocabulary of plastic that hints at other ways of imagining the body/system.

Magnus von Ziegesar, Untitled (Black), 2025

Magnus von Ziegesar, Untitled (Black), 2025

Even Pasha Smelyantsev’s role as curator folds into the same meta impulse. By assembling all these works into a semiotic gradient, they perform curation itself as collage-making. They also contributed their own small painting, BasedVisionNNJ (2025), which looks almost like a tarot portal — a card leading us into a meta-world. Pasha often “tries not to talk about her work too much,” letting the images speak for themselves, and that restraint makes their curatorial presence feel like another image folded into the show.

Pasha Smelyantsev, BasedVisionNNJ, 2025

Pasha Smelyantsev, BasedVisionNNJ, 2025

In the end, Parallax: Traversing Image and Text doesn’t read like a traditional exhibition so much as a projection of a collective state of mind for young artists in 2025. It’s dense, frenetic, sometimes tender, and everywhere restless. It doesn’t hand you a single narrative; it asks you to navigate your own path through mandalas and memes, saints and slogans. In a time when “all the layers exist together,” the show embraces the layers. It suggests that our reality is not an either/or between image and text, past and future, irony and sincerity, but a kaleidoscope of simultaneity. You may not leave with any stright answers, but you leave feeling the pulse of a generation that sees the world in split screens and still believes there’s a code worth decoding. In an age of cultural overload, Parallax doesn’t look away — it stares straight into the kaleidoscope and finds, inside the chaos, a strange, cold, lucid kind of comfort.

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

"Parallax: Traversing Image and Text" Exhibtion Photo © 1969 Gallery

1. Wallace, David Foster. Infinite Jest. Little, Brown and Company, 1996. The book is very much about all kinds of addiction, but it's also about the things we choose to assign value to influence the extent of our happiness as humans in modern America.

2. Kundera, Milan. The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Translated by Michael Henry Heim, Faber and Faber, 1985. The book is a meditation on how, in a world without inherent meaning or eternal return, love, desire, and history drift into a fragile lightness that both liberates and devastates.

Serena Hanzhi Wang

Serena Hanzhi Wang (b. 2000) is an award-winning art proposal writer, multimedia artist, and curator based in New York City. Her work spans essays, exhibitions, and installation Art—often orbiting themes of desire and technological subjectivity. She studied at the School of Visual Arts’ Visual & Critical Studies Department under the mentorship of philosophers and art historians. Her work has appeared in Whitehot Magazine, Cultbytes, SICKY Mag, Aint–Bad, Artron, Art.China, Millennium Film Workshop, Accent Sisters, MAFF.tv, and others.

view all articles from this author