Whitehot Magazine

October 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

October 2025

Anthony Haden-Guest on Art and Books

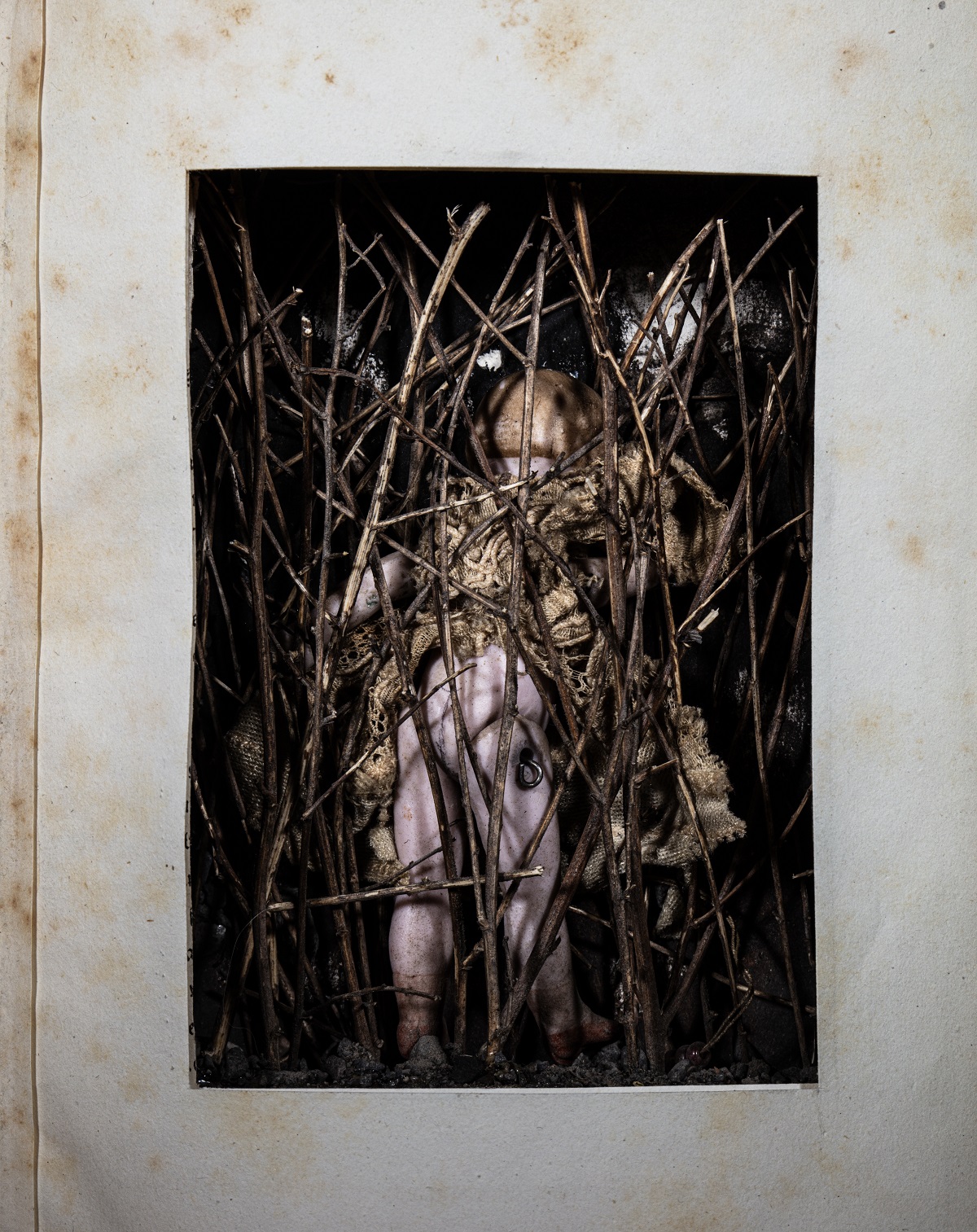

Heide Hatry, Homage to Joseph Cornell

Heide Hatry, Homage to Joseph Cornell

By ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST August 17, 2025

Byzantine artists would often paint a holy man holding a book or scroll, as too did artists during the early Italian Renaissance and in 1480 Botticelli and Ghirlandaio were each commissioned to paint saints, respectively Saint Augustine and Saint Jerome, in their book-equipped workplaces. The meaning assigned to books by artists darkened with the Vanitas paintings by 17th century Dutch masters, works in which a book, leaning against a skull, supporting a skull or spread open in front of a skull is messaging the foolishness of worldly aspirations.

The coming of Modernism and the energies it unleashed often brought artists and writers constructively together. Such as Picasso and Guillaume Apollinaire, the poet and critic, who introduced Picasso to Braque, coined the term Cubism and published a book about it in 1913. Picasso made art for an Apollinaire memorial after his death and himself wrote over 340 poems between the ‘30s and the ‘50s. Indeed the falling apart of his marriage to Olga Khokhlova in 1935 caused him to stop painting for about a year and focus on his poetry. A statement by Picasso that his poetry would outlive his art has been quoted but it has’t been proven that he actually said it.

Also close to artists was the novelist, Philip Roth, whose friends included his Woodstock neighbor, Philip Guston. For Guston this friendship was pivotal. Drawings he made generated by Roth’s mocking novel about the Nixon administration, Our Gang, signalled his move from the Abstract Expressionist manner in which launched his career into the feral cartoonery which made it blossom.

That was then. It’s no news that book reading is rapidly declining. But it’s not just a numbers game, there has also been a collapse in the quality of books which become best sellers, as David Brooks made clear in his July 24 New York Times column, When novels mattered. Which makes the way some artists have always used books rather timely: As art material.

Consider one fore-runner, John Latham, a Brit, and a member of the Independent Group, a fore-runner of Pop helmed by Richard Hamilton and Eduardo Paolozzi. Between 1964 and 1968 Lathan put on a number of happenings in the UK, one in the US, which he called Nights of Skoob Sadness, skoob being books spelled backwards, during which he built books into towers and set them on fire. This was controversial, given Nazi book-burnings. “It was not in any degree a gesture of contempt for books or literature,” Latham declared, noting that the books he picked were part of what he called the “Mental Furniture Industry” and full of “false truths”.

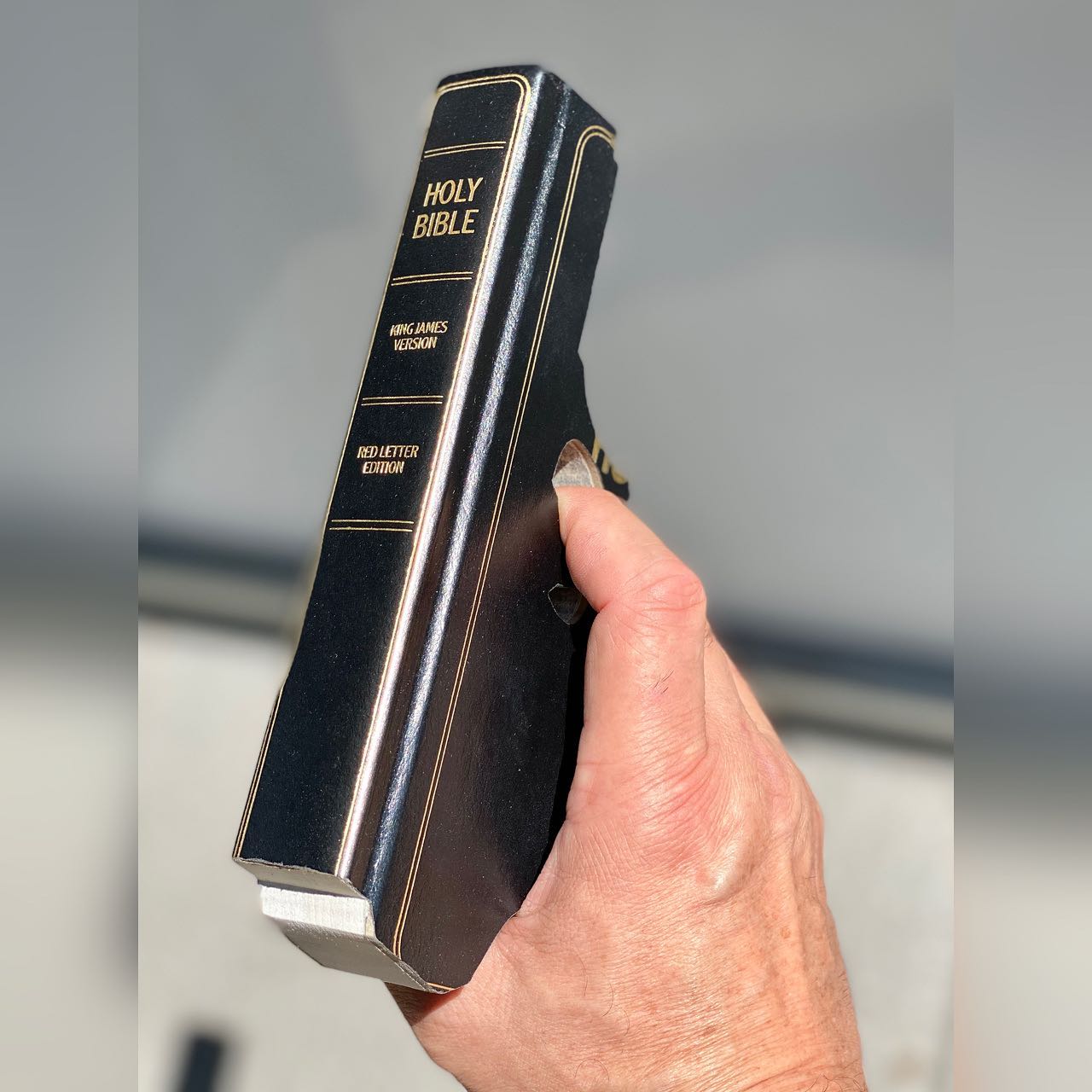

Robert The, The Holy Bible

Robert The, The Holy Bible

Latham’s book burnings had been Performance art but other artists use books to make actual artworks. Robert The, a New York-based artist and mathematician, picks his books carefully and carves them into different shapes, a process about which he is close-mouthed, merely commenting that carving paper is harder than carving wood. He has carved books into scorpions and lobsters but understandably his most remarked upon pieces are his Book Guns. Volumes from which these have been carved include Marshall McLuhan’s The Medium is the Message, JD Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye and the Holy Bible. He has described his process thus: Books (many culled from dumpsters and thrift store bins) are lovingly vandalized back to life so they can assert themselves against the culture which turned them into debris.

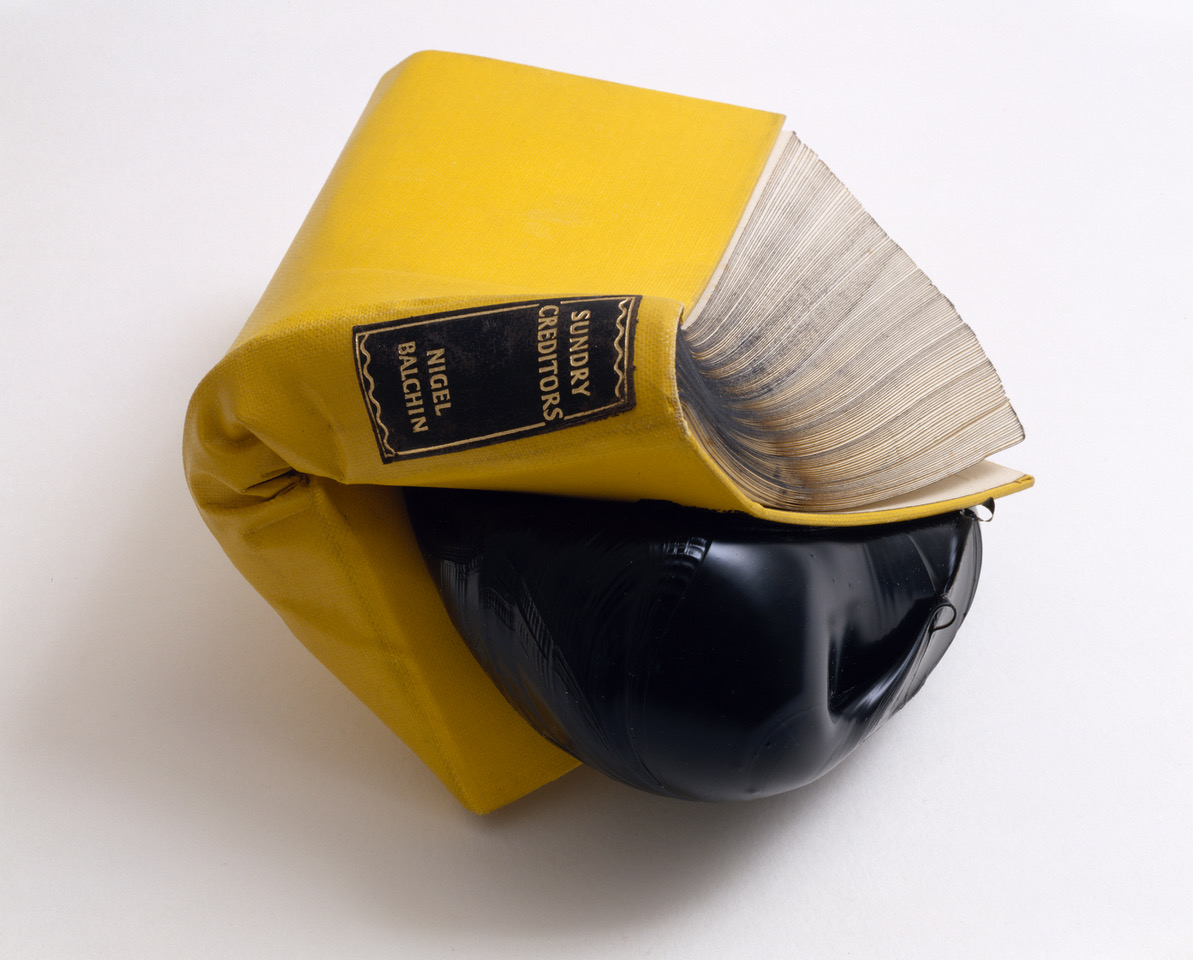

John Callan 2002.'Sundry Creditors' Paper and Silicone Rubber. 19 by 16 by 12cm

John Callan 2002.'Sundry Creditors' Paper and Silicone Rubber. 19 by 16 by 12cm

Jonathan Callan, a British artist who uses books as his principal art material, writes Most people will rarely think of a book as an object, the words within are regarded as far more important than the form without, he has written. He added I began to regard books in the same way a potter might regard clay, and he uses his clay equivalent in a variety of ways.

Many of his pieces are large abstractions, whose bookish origins do not declare themselves. Not so the three here.

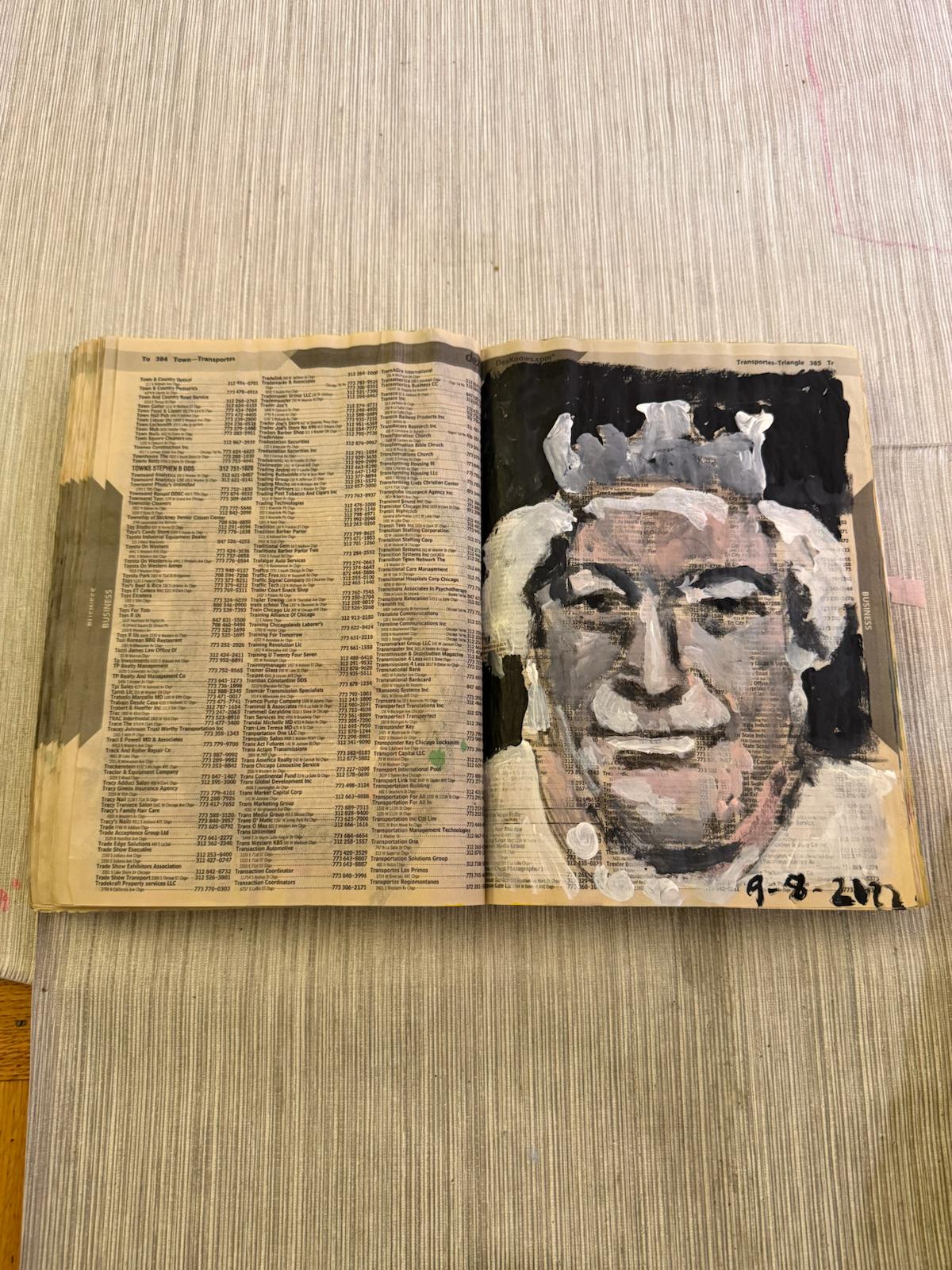

Some artists have chosen to work with non-book books, such as the telephone books Franz Kline, the Ab Ex, would use as sketchbooks when developing a concept. Dove Bradshaw, the artist, remembers seeing a Kline sheet from one of these hung on Leo Castelli’s wall. Geraldo Perez, a New York artist born in the Dominican Republic, was turned on by seeing a heap of such telephone directories lying on a New York street during a snow storm. ”I saw a whole pile of them,” he said. “I felt bad for them because they were going to blow away. And I had read about Franz Kline. It was cheap paper. They were going to get wet, they were going to get ruined.” These were telephone books. “It’s about memories. I wanted to give them life.”

Geraldo Perez

Geraldo Perez

Dove Bradshaw. a New York artist, got massive attention in 1979 for the Duchampian coup of declaring that a firehose in the Met was her artwork, a move that ended with the Met agreeing to sell Bradshaw’s postcards, picturing the hose, which she gifted them. That same year she read a piece by Alfred Jarry, the 19th century French writer, author of the play Ubu Roi, a prototype of Dada, Surrealism, the Theatre of the Absurd, and much else. Bradshaw observes that Jarry had been well-read in both science and literature but that his piece had been an attack on books. “Jarry called them Disembraining Machines,” she says. “He said you were dumber than dumb if you followed or read books. What you lose is your intuition.”

Accordingly Bradshaw took a book she had found on the street and got to work. “I covered it in axle grease … very thick …about half an inch I think,” she said. “It was amber and translucent and it hardened and cracked. Which I liked, wonderful cracks. And it was, of course, impossible to read the book.”

Bradshaw also found her second art volume and it came into her hands that same year. It was a burned book and she felt it did not require the work of her hand. “I just found it in the trash,” she says. “The burn it had this beautiful wave of a shape. I had already done the Disembraining Machine so I thought I would present this one too.”

Other artists are absolutely into quality books. such as Heide Hatry, a German artist who has long lived in New York, but got into books in her home-town, Heidelberg. “I was selling rare books there for twenty years,” she says. It began so. “I met my husband in ‘85. We moved in together and did not have money to pay the rent. So we just sold the books we had at home.

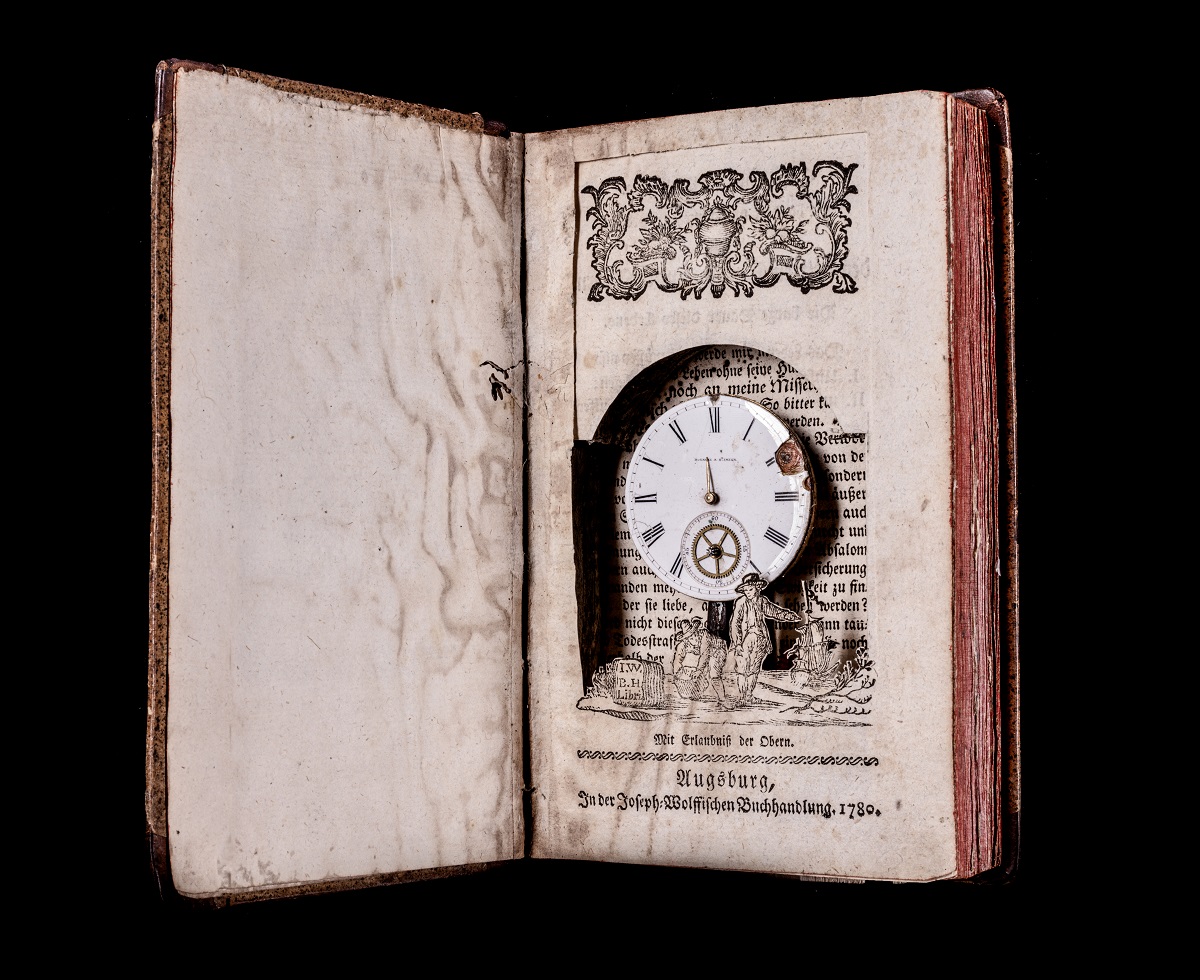

Heide Hatry ClockBookII

Heide Hatry ClockBookII

“I handed out flyers on the street to show where the “bookstore” was. They had to go upstairs, through our toilet, into a tiny room. And in one day we made the rent for the entire month. So we thought wow! This is fantastic! We just buy a few more and try it again. We eventually ended up with a five-floor rare book store.”

How did this morph into turning books into artworks?

“Because I was an artist and I wanted to make some art,” Hatry says. “And I didn’t have time because I had a baby. I didn’t even have a studio. I could only work on a small scale. I had a table, I had art materials. I could only work on a small scale, and only for an hour here or there at a time, so I decided to make just one page of an artist’s book a day, sometimes using existing volumes that were of no use to the shop. I painted, collaged, sometimes erased existing text or added a new one, and after a month or two, I had finished a book.”

The marriage blew up and in 2003 Hatry came to New York.

Her art project ripened. The pre-existing elements in each volume are crucial. “I was interested in using a book with a beautiful binding, beautiful paper … a beautiful front paper … the books that I collected to make these art books needed to have something that I liked … a nice cover or a nice end paper … it could be the binding, it could be the paper. In my current show at Ivy Brown Gallery, which ends this week, I have mostly excavated books to form box-like structures into which I insert assemblages.”

Was what the book was actually about important to her?

“It was. I love the content of a book.”

Which is why Heide Hatry has hardly ever turned a book with contents she truly likes into one of her artist books. “Because I would be destroying the contents,” she says.

Anthony Haden-Guest

Anthony Haden-Guest (born 2 February 1937) is a British writer, reporter, cartoonist, art critic, poet, and socialite who lives in New York City and London. He is a frequent contributor to major magazines and has had several books published including TRUE COLORS: The Real Life of the Art World and The Last Party, Studio 54, Disco and the Culture of the Night.

view all articles from this author