Whitehot Magazine

September 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

September 2025

Sol LeWitt and Phong H. Bui: The Rule and the Hand

Phong H. Bui & Sol LeWitt, installation view. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Christopher Stach.

By RAPHY SARKISSIAN, September 23rd, 2025

Sol LeWitt’s grid was a space of thinking, a modernist ideal meant to postpone the hand’s errant trace. It was a denial of subjectivity, a diagram for a work to be built by anyone for the idea to be everything. Yet Phong Bui’s work, in its layered, visceral physicality, stands not in opposition, but as a resonant presence within this rational space. Bui’s abstract drawings, presented adjacently to his portraits, declare the undeniable corporeality of pencil marks that define faces and unveil the very fabric of the work. This exhibition is less a conversation between two artists than it is an investigation into a single site of tension: the point where the mind’s rule and the body’s compulsion collide. We see Bui’s obsessively worked surfaces—his frenetic, imperfect lines—returning body-memory to the very grids LeWitt had sought to sterilize.

The interplay between Bui’s spontaneous expression and LeWitt’s structured approach uncovers revelatory insights. It rises through the cracks of the cool, rational surface LeWitt prescribed, disclosing what was always there beneath: the artist’s involuntary impulse, the bodily trace, the irrational desire to make a mark and to leave a residue. The intellectual purity of the conceptual artwork is here confronted by the disarray of material life, reminding us that even the most determined effort to escape the human hand cannot erase its echo. In doing so, the exhibition stages a confrontation not of styles but of logics, presenting a structural dilemma at the heart of conceptualism. LeWitt's work is emblematic of minimalism's desire to banish the hand, to replace the artist's personal trace with the impersonal, reproducible instruction, rendering physical manifestation secondary. But here, Bui's work demonstrates that the conceptual grid is always haunted by its own material life, and that the mark is never fully divorced from the body that makes it.

Sol LeWitt, Windows, 1980. Seventy-two color photographs mounted on board. 35 3/4 x 32 1/4 inches, framed. Edition of 20. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

LeWitt’s Windows (1980), a printed image displaying 72 color photographs of architectural façades, exemplifies Walter Benjamin’s concept of “aura” and its fate in the age of mechanical reproduction. Benjamin argued that the aura of a work of art stems from its unique presence in time and space, intertwined with tradition and ritual. In his 1931 essay “A Short History of Photography,” Benjamin writes, “What is aura? A peculiar web of space and time: the unique manifestation of a distance, however near it may be.” [1] This quality, the irreplaceable authenticity of a moment captured in a singular image, is what Benjamin perceived in early portraiture, which was treated as a unique work of art rather than a mass-produced reproduction. In his landmark 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” however, Benjamin contends that mechanical reproduction diminishes this aura. He notes, “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: Its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” In this way, the photograph's endless reproducibility detaches it from its original context and ritualistic value, emphasizing its widespread accessibility over its unique presence.

With serial images of architectural moments, LeWitt’s Windows foregrounds the potential waning of the aura in an era saturated with mechanical reproduction, as articulated by Benjamin. The mechanical proliferation of photographic images—offering democratizing access and highlighting their indexical connection to reality—prompts a reconsideration of aura. Hence, the array of randomly chosen architectural façades within Windows operates as a typological register of sameness and difference, defining aura by its presence and absence.

Sol LeWitt, Open Cube Structure, 1997. Painted wood, 20 x 32 x 6 1/2 inches. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

In turn, LeWitt’s Open Cube Structure (1997), a stark, white wooden matrix, rhythmically frames the spatial bareness of the gallery. This spatial grid serves as an uncanny diagrammatic outline for Bui’s geometric organization of resemblance and abstraction in his ongoing Symphony series. These suites of drawings offer a contemporary reconsideration of the concept of aura. Bui converts mass-circulated photographic portraits of artworld figures into linear and painterly pencil drawings, presenting them within a grid-like framework that also contains nonrepresentational, rhythmic patterns. In doing so, Bui interrogates representation and abstraction concurrently. His drawings thus challenge modernism’s haunted embrace of mechanical reproduction over draftsmanly representation. While conceptual art, championed by figures like LeWitt, intended to democratize and intellectualize art, the absence of the artist’s unique “mark” unexpectedly opens a space where the latent desire for constructed likeness re-emerges within Bui’s re-embodiments and pulsing gestures in graphite.

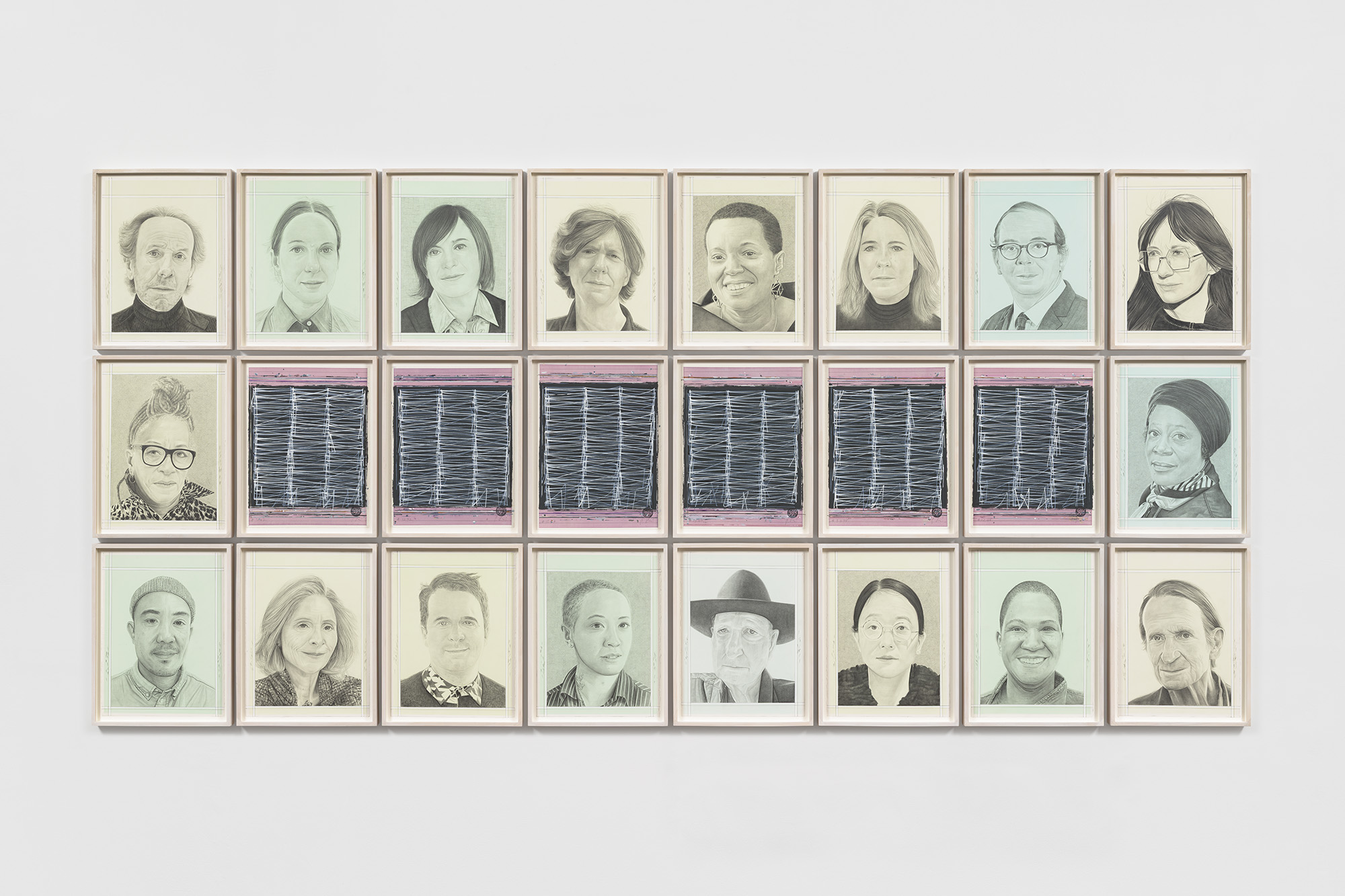

Phong H. Bui, Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), 2024-25. Portraits: Pencil on paper. Meditation Paintings: Gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 50 1/2 x 105 1/2 inches, overall. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

Bui’s Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), dated 2024-25, stands as a highlight within this exhibition, offering an inquiry into the fundamental tenets of artmaking. In Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), the traditional genre of group portrait has been reconfigured through a tabulation of eighteen distinct portrait drawings that are formally arranged to encircle six linear abstractions from Bui’s Meditation Paintings series. Through this deliberate composition, the viewer is prompted to engage with the inherent conditions of perception: a recognition of certain artworld figures from a shared cultural context, eliciting an immediate sense of familiarity. Yet such figures are directly juxtaposed with the equally compelling presence of individuals whose identities may be unknown. This dynamic interplay underscores both personal connections and the broader, sometimes unrecognized, collective interactions that shape the art world. Ultimately, the work illuminates the continuous interplay between established art historical accounts and the vital, yet less defined, collective interactions that constantly reshape the cultural landscape.

Phong H. Bui, Sonia Boyce, 2024. Detail of Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), 2024-25. Pencil on paper, 16 1/2 by 12 3/4 inches, framed. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

In Symphony #6 Bui engages with photographic appropriation, where the elusive Barthesian punctum—that decisive, albeit unpredictable, detail that "pricks" the viewer—emerges through his expressive manipulation of graphite. Through this process, Bui transforms mass-circulated images of cultural figures into nuanced portraits, each with its own evocative details. The Italian Transavanguardia painter Enzo Cucchi is portrayed gazing at us intently. Adjacently, the keen observation of artist Sarah Cwynar recalls her critical stance on consumer culture. The arrangement continues to the intuitive countenance of the museum director Madeleine Grynsztejn, placed next to the androgynous drawing of Thurston Moore, whose vocals in the song “Incinerate” of Sonic Youth resonate in our memory. The buoyant smile of Amanda Williams is adjacent to the introspective outlook of Jacqueline Humphries. Our gaze meets that of Laurent Le Bon, president of Centre Pompidou, while visual and sound artist Lisa Alvarado’s contemplative stare transcends the confines of the pictorial field. British multimedia artist Sonia Boyce’s confident yet reserved gaze is also directed at us, highlighted by an elegant scarf and turban. In contrast, video pioneer Ed Bowes’s stare radiates a sheer engrossment.

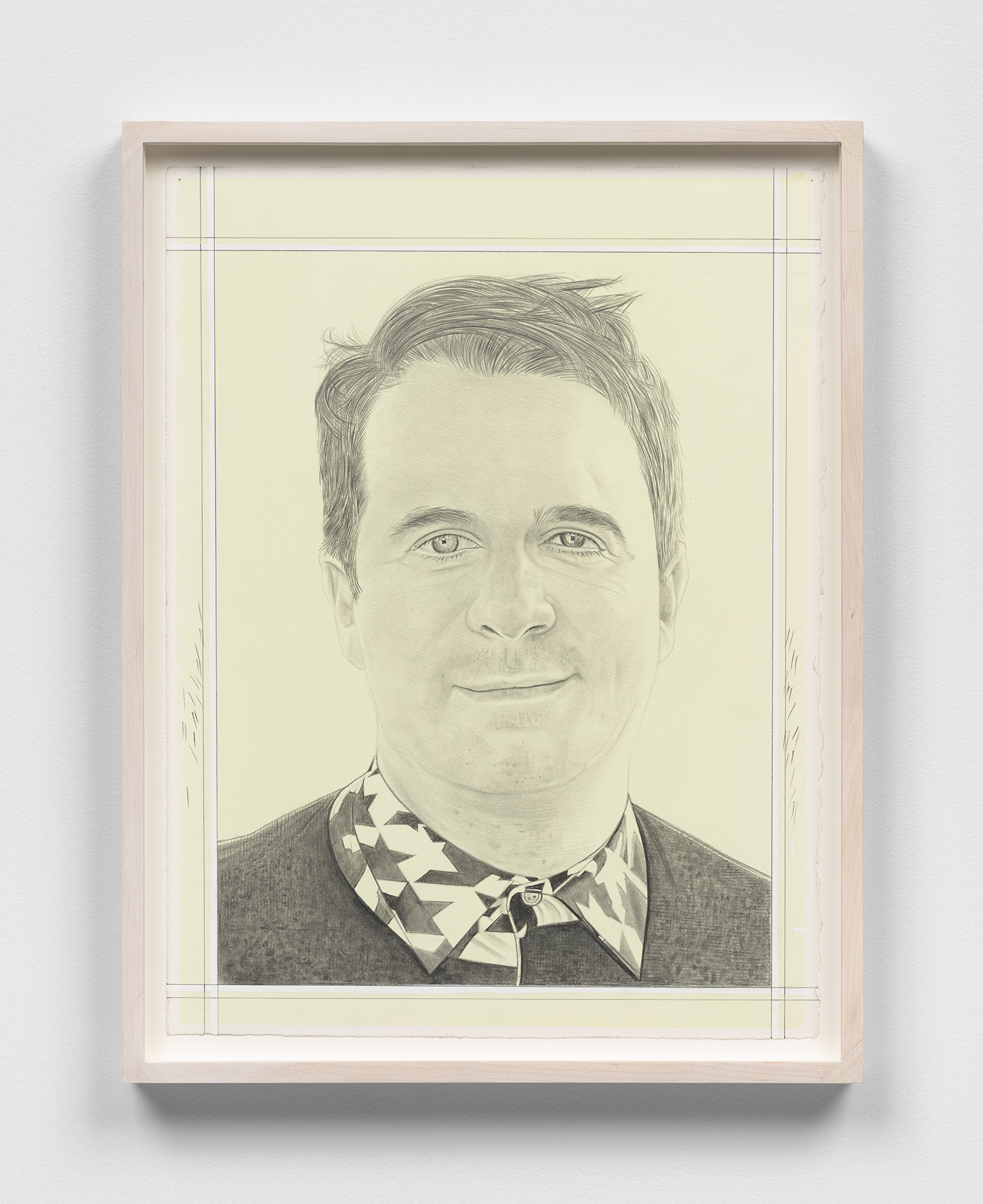

Phong H. Bui, Andrés Jaque, 2024. Detail of Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), 2024-25. Pencil on paper, 16 1/2 by 12 3/4 inches, framed. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

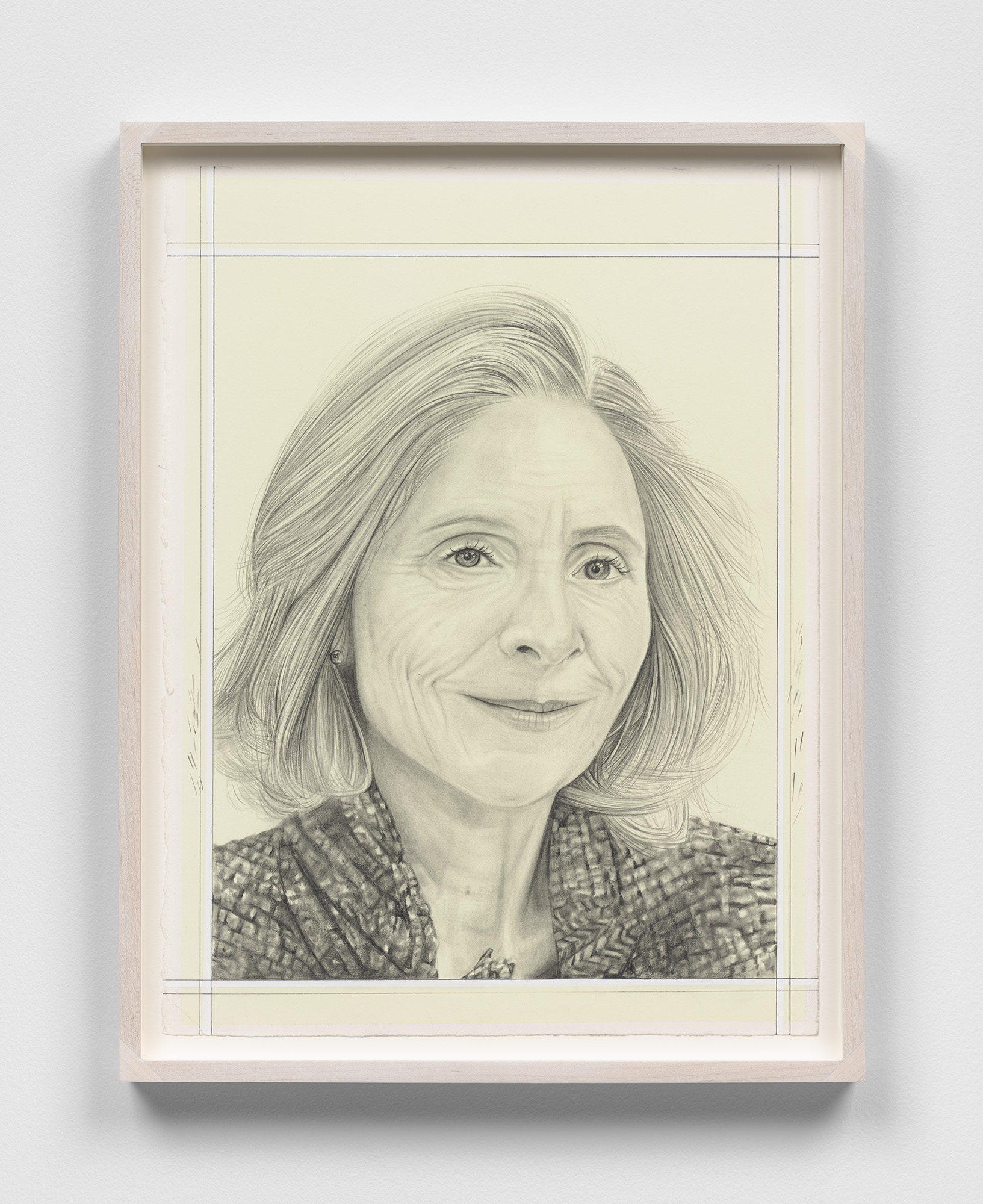

There is a sense of genuine innocence conveyed in the honest smile of American poet Pamela Sneed. The intuitive stare of the American sound artist Christine Sun Kim confronts us with unflinching clarity. Bui’s depiction of Bruce Nauman is notably distinguished by the sculptor’s cropped fedora hat. In a striped shirt, performance and multimedia artist Sin Wai Kin conveys an impenetrable gaze. The bold houndstooth pattern of the shirt provides a graphic counterpoint to the gentle smile of Columbia University’s dean of architecture Andrés Jaque. Art historian Emily Braun’s thoughtful introspection is softened by a warm smile. Vietnamese-American installation artist Tuan Andrew Nguyen’s pensive beam is directed toward an enigmatic scene. The British Afro-Caribbean multimedia artist Veronica Ryan looks upon us with a mixture of assertiveness and reserve. Operating within a matrix of simulated resemblance, Bui's interlaced threads create a constructed image that is irrevocably dislodged from its indexical tether. It is a work separate from any presumed "truth," registering not just as drawing, but as a semiotic intervention that foregrounds the very condition of image-making within our post-medium age. [2]

Phong H. Bui, Emily Braun, 2025. Detail of Symphony #6 (for Richard Serra), 2024-25. Pencil on paper, 16 1/2 by 12 3/4 inches, framed. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

As a given portrait of Bui is a transcription of a photograph into a hand-drawn image, this approach brings about a fundamental paradox: while photography is often seen as a direct, mechanical imprint of reality, drawing from a photograph introduces the artist’s hand, interpretation, and subjective experience back into the equation. The process gives rise to a dialectical interplay between the seemingly objective source material and the inherently subjective act of artistic rendering. Such a dichotomy recalls not only the theoretical foresight of Benjamin, but also that of André Malraux.

In a vast, democratic concept of “the museum without walls,” or art accessible through reproductions within an art book, Malraux envisioned transcending the physical limitations of traditional museums. [3] While Benjamin argued that mechanical reproduction diminishes an artwork’s aura—its sense of authenticity and history—Bui’s process reclaims it. He utilizes and further transforms already-reproduced and circulated images, first as supplements to interviews in The Brooklyn Rail and now as visual symphonies for collective experience in an exhibition space. By translating a photograph into a drawing, Bui invites the viewer to reconsider the concept of aura, as each drawing is transmuted into a distinct depiction with its own semblance and subjective elements. This project uncannily recalls the words of LeWitt: “Once given physical reality by the artist the work is open to the perception of all, including the artist. (I use the word “perception” to mean the apprehension of the sense data, the objective understanding of the idea and simultaneously a subjective interpretation of both.) The work of art can only be perceived after it is completed." [4]

Phong H. Bui & Sol LeWitt, installation view. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Christopher Stach.

Indeed, as Alexander Nagel’s insightful essay for the exhibition explains, the apparent binary between two methodologies—Bui’s personal touch and LeWitt’s instructional approach—is in reality tightly knit, revealing underlying connections and shared concerns. “Bui’s slow processing has the effect of reducing the individuality that flashes out of each photo. … the effect results from his commitment to suppressing his own individual expression, as he undertakes the quixotic task of putting portraiture through something like the LeWittian system,” Nagel reflects. [5]

Though Bui does not use instructional parameters in the manner of LeWitt, his works reflect the collaborative and communal aspects of artmaking. As the publisher and artistic director of The Brooklyn Rail, Bui has fostered a vibrant intellectual and artistic community, providing a platform for critical discourse and the exchange of ideas. This dedication to community and artistic dialogue resonates with LeWitt’s commitment to systems of collective execution and widespread dissemination of the artistic concept, as reflected in the collaborative nature of his wall drawings and his insistence on the accessibility of the artistic idea. The very act of commissioning others to execute LeWitt’s wall drawings is a democratizing gesture, extending the act of artmaking beyond the confines of the artist’s studio.

Phong H. Bui, Symphony #7 (for Tony Bechara), 2025. Portraits: pencil on paper. Meditation Paintings: gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 50 1/2 x 105 1/2 inches, overall. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

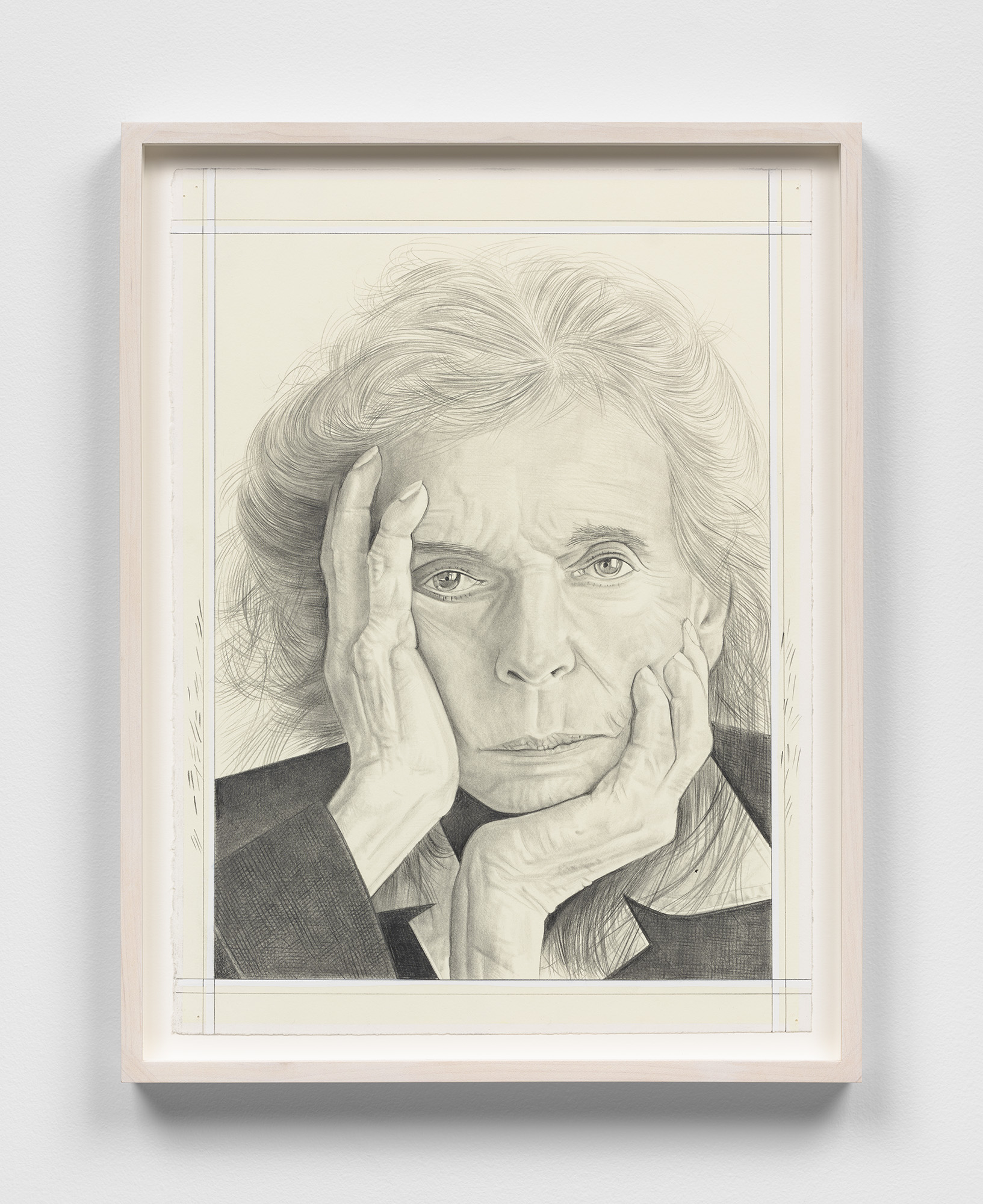

In Symphony #7 (for Tony Bechara), 2025, another highlight of the exhibition, Bui translates photographic images into hand-drawn pencil marks to represent a social collective. His meticulous process is guided by a grid system, an approach that resonates with the methodologies of Albrecht Dürer and Chuck Close. This matrix facilitates the image's precise transfer and scalar manipulation, a structural element at times highlighted in the final work. The constellation portrays eighteen figures from visual culture: Pepe Karmel, Suzanne McClelland, Alvaro Barrington, Pat Steir, Anthony Roth Costanzo, Monique Truong, Georges Adéagbo, Alice Notley, An-My Lê, Isaac Julien, Matt Dillon, Lubaina Himid, Alexandre Lenoir, Ouattara Watts, Leelee Kimmel, Michael Auping, Kay WalkingStick, and Chuck Close. Through the material interplay of paper, pencil, and the artist’s hand, Bui renders each subject as an afterimage of the photographic trace.

Phong H. Bui, Pat Steir, 2024. Detail of Symphony #7 (for Tony Bechara), 2025. Portraits: pencil on paper. Meditation Paintings: gouache, watercolor, and pencil on paper, 50 1/2 x 105 1/2 inches, overall. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

Concurrently, this archival register of eighteen portraits establishes a framework for the interplay with six abstract drawings. Both the portraits and the nonfigurative sketches share a graphic vernacular rooted in drawing. In his meditative abstractions, Bui explores the inherent properties of line, culminating not in visages but in the phenomenal manifestation of luminosity. As the artwork simultaneously becomes an object of self-referential inquiry, grounded in its own material and formal operations, it invites reflection. Stepping back, one can reflect not only on the recognized and unrecognized faces but also on the profound capacity of lines to abstractly embody space and light.

Sol LeWitt, Cube, 1991. Gouache and pencil on paper. 24 1/2 x 32 1/4 inches, framed. Courtesy of Craig Starr Gallery, New York. Photo: Pierre Le Hors.

Far from simplistic formalist exchanges, this exhibition reveals a charged dialogue between Sol LeWitt's conceptually-driven framework and Phong H. Bui's performative engagement with materiality. This dialectic demonstrates how distinct formal systems, operating within our post-medium time, collectively enact and continuously reconfigure the possibilities of aesthetic production through a guiding rule and the artist's own hand.

Departing from the gallery space, the images we saw begin to gradually recede from our immediate consciousness, mirroring the lingering fade-out of Sonic Youth’s “Incinerate.” WM

Notes

1. See Walter Benjamin, Selected Writings, ed. Michael Jennings (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1999-2006).

2. On the post-medium condition, see Painting Beyond Itself: The Medium in the Post-Medium Condition, ed. Isabelle Graw and Ewa Lajer-Burcharth (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016).

3. See André Malraux, The Voices of Silence, trans. Stuart Gilbert (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1978).

4. Sol LeWitt, “Paragraph on Conceptual Art,” Artforum, 5, no. 10 (Summer 1967), pp. 79-83.

5. Alexander Nagel, “Drawing as a Clearing,” Craig Starr Gallery viewing room.

Phong H. Bui & Sol LeWitt

Craig Starr Gallery, New York

July 17, 2025 — October 4, 2025

Raphy Sarkissian

Raphy Sarkissian received his masters in studio arts from New York University and is currently affiliated with the School of Visual Arts in New York. His recent writings on art include essays for exhibition catalogues, monographs and reviews. He has written on Rachel Lee Hovnanian, Anish Kapoor, KAWS, David Novros, Sean Scully, Liliane Tomasko, Dan Walsh and Jonas Wood. He can be reached through his website www.raphysarkissian.com.

view all articles from this author