Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Trevor Guthrie’s Black Magic Provocations

An interview with the Swiss-based artist on his monumental charcoal drawings, anti-productionism, and wrestling authorship from machines

By STEPHEN WOZNIAK August 18, 2025

Trevor Guthrie's studio in Switzerland feels like a throwback—long rolls of thick white paper mounted on five-meter panels, compressed charcoal sticks scattered everywhere, and old black-and-white photos pinned to the walls. But what strikes me most isn't the remarkable works therein—it's the steady, focused intensity that permeates the space, born from decades of working in humanity's oldest drawing medium. The Scottish-born, Canadian-raised artist has spent twenty years developing a singular practice built around massive charcoal drawings that oscillate between the truly sublime and the almost absurd. A crocodile lounges on an unmade bed, a lobster confronts a speeding train, Jeff Koons' polished bunny crashes and burns like the Hindenburg. Following his 2024 retrospective of 85 works spanning twenty years, Guthrie's anti-productionist stance feels increasingly urgent in our age of algorithmic artmaking.

Installation view of Trevor Guthrie Drawings: 2004-2024 at Villa Bührle in Zürich, Switzerland, September 2024.

Installation view of Trevor Guthrie Drawings: 2004-2024 at Villa Bührle in Zürich, Switzerland, September 2024.

Stephen Wozniak: Your background reads like a peripatetic novel—Scotland, Manitoba, South Africa, Ontario, British Columbia. How did this nomadic childhood inform your artistic sensibility?

Trevor Guthrie: Both my parents were working-class factory workers. There was this migration happening—lots of immigrants from Great Britain and Scotland coming to Canada in the late 1960s. We ended up in Selkirk, Manitoba, which I think has more polar bears than people (laughs). My father wanted to go to Rhodesia when it was still Rhodesia, took us to South Africa for a year, then basically left us there—my mom and four kids. I was six when their marriage ended. We eventually made it to Cambridge, Ontario, where I spent about fifteen years, then moved to British Columbia.

I dropped out of high school with a ninth-grade education and left home at fifteen. I went through rough teenage years and bounced from job to job. When I was about eighteen or nineteen, I was walking down a street in Vancouver—this was 1984 or '85—almost flat broke, but I took my last twenty dollars and bought art supplies. I just declared, "I'm going to be an artist." Because drawing was what made me happy as a kid.

SW: There's something mythic about that moment—the broke artist's conversion experience. But you spent twenty years painting before your breakthrough with charcoal. What precipitated that shift?

TG: I painted for twenty years without any real success. But I sold a few pieces to friends. When I moved to Switzerland, I was still working in restaurants, paying dues and paying rent. A friend who was a DJ asked me to decorate the walls for a Halloween party at this bar in Zurich. I thought, "I can do some drawings." I was already accomplished with charcoal, but it wasn't my focus. So, I did ten big drawings for this party—one night only. The crocodile on the bed was from that series. My fingers were literally bleeding by the time I finished them in three weeks from working so fast.

That was the breakthrough. I sold a couple, including the crocodile. It was 2003. I realized the scale of the work was where I was headed. Got my studio set up with large panels, big rolls of paper—and really committed to the drawings.

The Guest Room III, 2017, charcoal on paper, 65 x 95 cm

The Guest Room III, 2017, charcoal on paper, 65 x 95 cm

SW: Let's talk about charcoal itself. It's humanity's most ancient mark-making tool, carries this weight of prehistory, of burned organic matter. There's something primal about it that seems essential to your work's meaning.

TG: Even though I dropped out of high school, I later went to a little provincial art school in Victoria BC, Canada, where we had life drawing classes—that's when I really picked it up. After graduation, I did these twelve-hour drawing sessions with my friend Noah Becker, taught by an older artist named Glenn Howarth who was also this LSD guru. We'd have six different models, a new model every two hours, who did twenty-minute poses for half of a day. I dropped acid before class started and—wow! I was batting a thousand. It was just amazing. Sold all forty drawings from those sessions, too.

That LSD trip really solidified charcoal in the background. I knew this was the medium I could always fall back on, though I never thought I could have an art career just drawing. Of course, I was wrong.

SW: Your sometimes lengthy titles often read like manifestos, such as "Landscape with the Trans-Continental Express vs. the Canon of Western Art—Manifested Here in the Form of a Tyrannical Crustacean." They're simultaneously explanatory and mystifying. What's the strategy there?

TG: The long titles are just amusement for me. I'm scrambling the meaning, making it more—or less—cryptic. Is it explanatory or taking the viewer down another path? That lobster piece references Jordan Peterson's theory about serotonin establishing territorial dominance in lobsters. The "Trans-continental" alludes to the recent trans movement. It's Peterson's crusty lobster fighting against progressive change. But, ultimately, I prefer people make their own interpretations.

SW: Your work consistently places the unexpected in mundane settings—wild animals in offices, bedrooms, domestic spaces. Is this your version of surrealism for the twenty-first century?

TG: It's about creating "Unsinnig"—the German word for absurd scenarios. Insert something absurd to create dramatic effect, like in a Fellini film. Animals work better as avatars than human subjects. Viewers can relate to an animal more easily, I feel. They don’t have to identify or know the person featured—they can relate on a more fundamental level without that baggage.

When I go on Instagram, there's a million empty, stylized human portraits uploaded every day. Animals, on the other hand, seem to present meaning, have purpose. There's a deep reason why they're in my drawings, though I can't say I know what that reason is.

Trevor Guthrie, Hindenbunny, 2008, charcoal on paper, 85 x 110 cm

Trevor Guthrie, Hindenbunny, 2008, charcoal on paper, 85 x 110 cm

SW: You've made explicit commentary on art world figures—particularly your "Hindenbunny" piece depicting Koons' crashing and burning sculpture, which was made during the 2008 financial crisis. There's real bite there.

TG: That was my anti-productionist statement. I hate productionism. Koons, Hirst, Warhol—they're factory artists, more businessmen than artists. And there's obviously room for them. I just reject it. My 2008 piece was commenting on both the financial meltdown and art market hype. It's funny because it became one of my most iconic pieces, but at the time I thought it was trite—a throwaway thing.

There's this Renaissance theorist, Alberti, who said in his book, De Pictura, that beautiful, expensive things like diamonds and gold are more valuable as paintings than the actual objects. I tested his theory at the most pedestrian level—what's the most common "bling" in the twenty-first century? My answer was car wheels. I did a series of fourteen wheel drawings and sold them all. His theory held up.

SW: So, your drawings were “more valuable” than the actual object depicted in terms of market value. However, it sounds like Alberti was maybe talking about how they also live on as artwork through history and in our mind, about the social milieu they reflect. Hopefully, your drawings have achieved both of those states. Speaking of bling, you've had some interesting encounters with artist Robert Longo, who you suggest has "mugged" your imagery over the years.

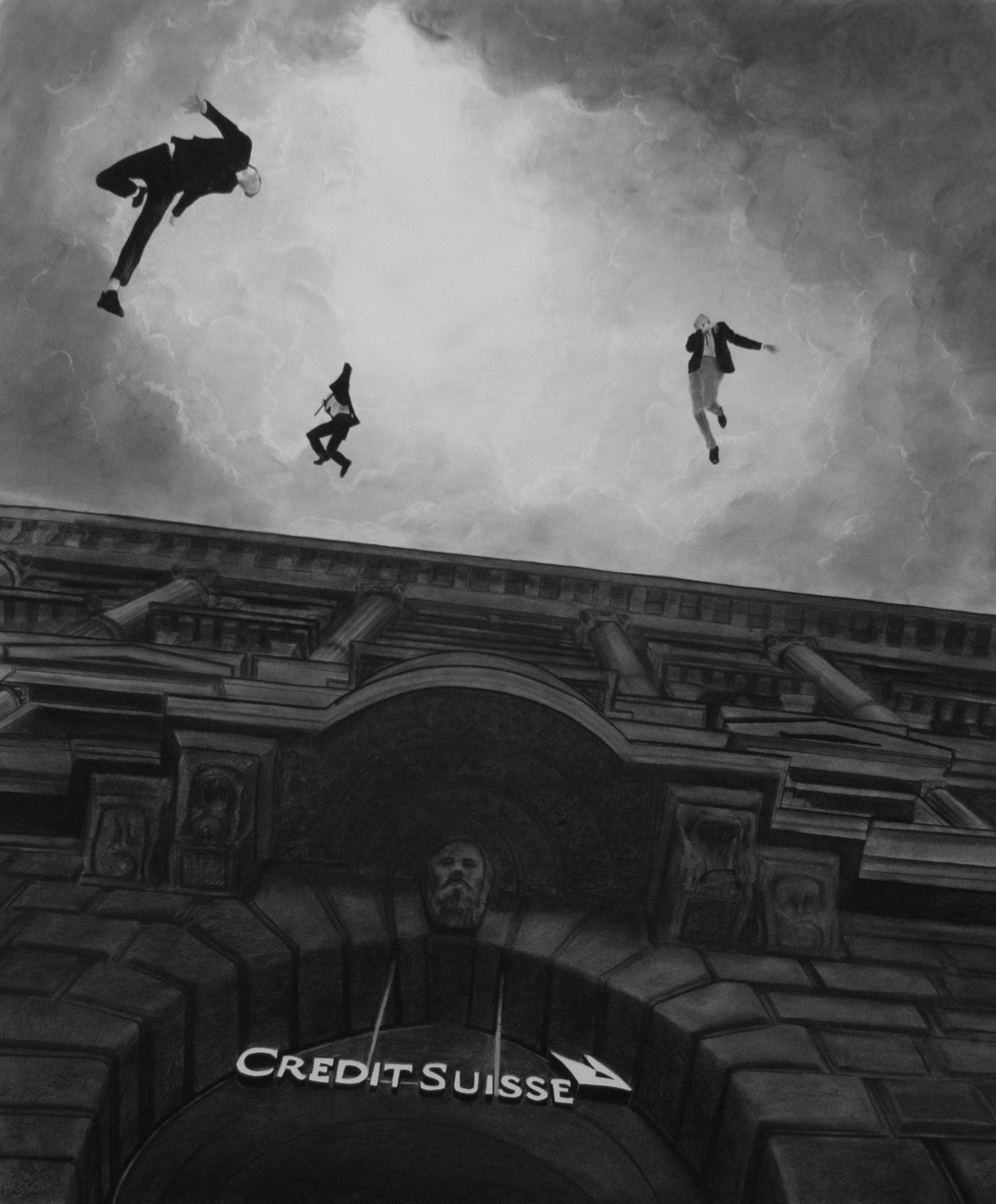

TG: He actually used one of my drawings as his Facebook profile picture years ago. I met him once outside the Jane Hotel in New York—he was very polite. But he's been lifting from me for years. The blingy chandeliers, the car wheels. I saw a snapshot of his studio on Instagram with a car wheel on the wall. But you know what? I'm honored to be influential. To punish him, I used his twisting, falling figures—making them suicidal jumpers—in my piece about the financial crash, M. Night Shyamalan’s The Happening, 2, placing them over a Credit Suisse bank sign.

Trevor Guthrie, M. Night Shyamalan`s The Happening, 2, 2014, charcoal on paper, 120 x 100 cm

Trevor Guthrie, M. Night Shyamalan`s The Happening, 2, 2014, charcoal on paper, 120 x 100 cm

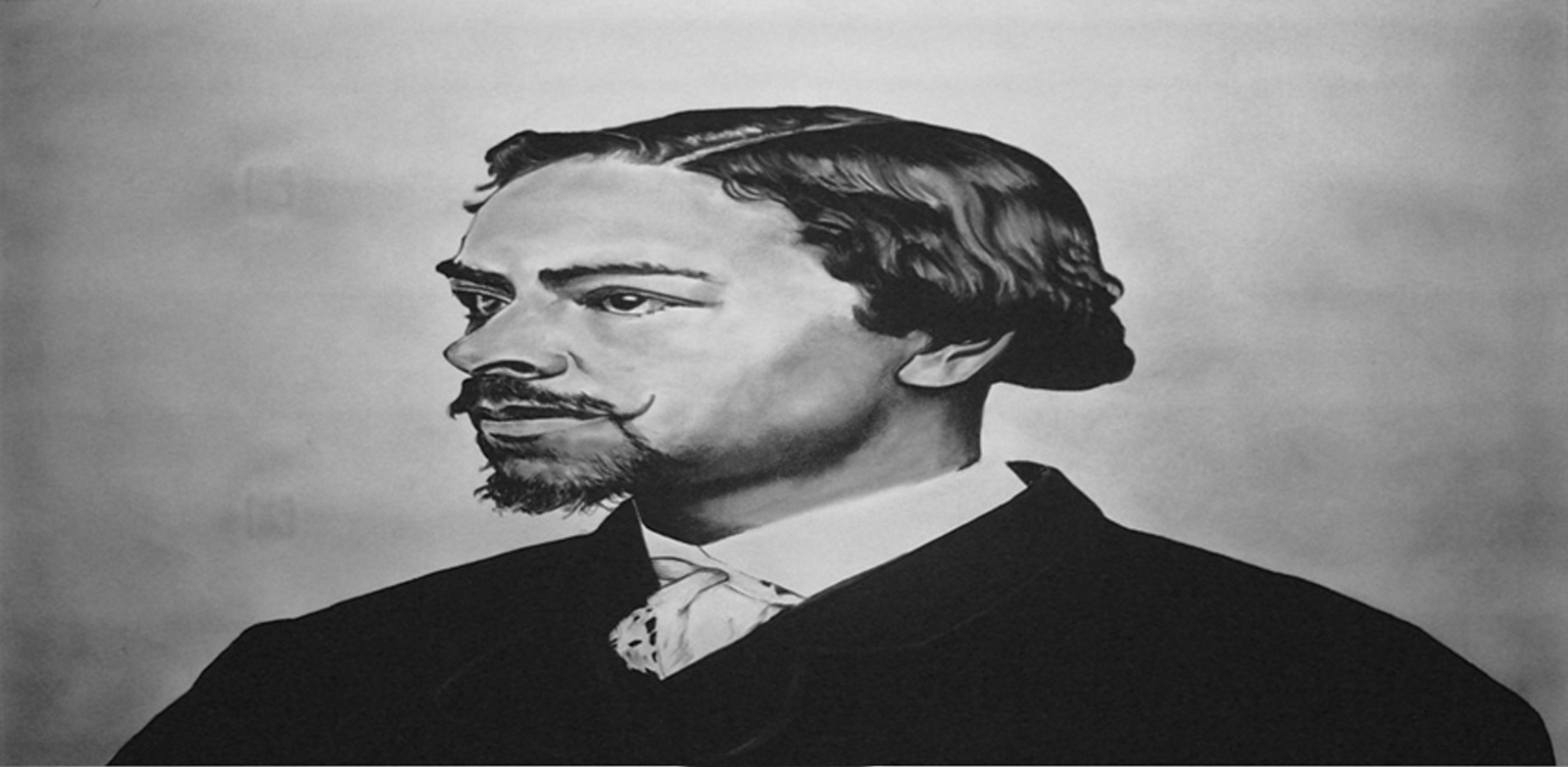

Trevor Guthrie, Anamorphic Study I, (Nasa McCurdy), 2021, charcoal on paper, 70 x 130 cm

Trevor Guthrie, Anamorphic Study I, (Nasa McCurdy), 2021, charcoal on paper, 70 x 130 cm

SW: Your anamorphic portraits elongate human heads into cinematic aspect ratios, and viewers have to look at them from the side to see them in normal perspective. There’s a fascinating lineage from Holbein's famous distorted memento mori skull in “The Ambassadors” to your more democratized approach to portraiture. What attracts you to this kind of optical manipulation?

TG: It started with a commission—a portrait of some Swedish rail commissioner. I couldn't get his likeness because I suck at drawing likenesses. I figured out how to stretch his image on the computer so it would work. By using that unusual format, I made it look more like him because I was unblocked from trying to get the exact likeness. I just followed the computer-generated form.

I did a series of eight, including a self-portrait. I was looking for three-quarter portraits in old black and white photographs. It just happened that some were historical figures, like Nasa McCurdy from the Underground Railroad. That added layers of meaning I wasn't originally seeking.

SW: There's something interesting about encouraging viewers to physically move to decode or process the image—art that demands choreography rather than passive consumption.

TG: Exactly. The viewer has to participate, has to work for it. It's not spoon-fed. In galleries, I watch people discover that they need to move, see them shift their bodies to suddenly understand what they're looking at. That moment of recognition is powerful—it's earned, not given.

SW: You experimented with AI-generated imagery but ultimately abandoned it. What was that interaction like?

TG: I got a grant to pursue AI work—this was early AI. I was generating hundreds of images, doing hundreds of prompts. There was something interesting about taking the oldest medium known to man—charcoal that cavemen used on cave walls—and combining it with hyper-new technology. The process generated weird surface textures I could improvise with, wrestling authorship away from the machine.

But I gave up after five or six pieces because I couldn't be the master. The machine won. It took too much compromise, too much prompting. It worked against my normal methodology. I think I can come up with good, weird shit on my own—like the lobster and the train. I don't need AI.

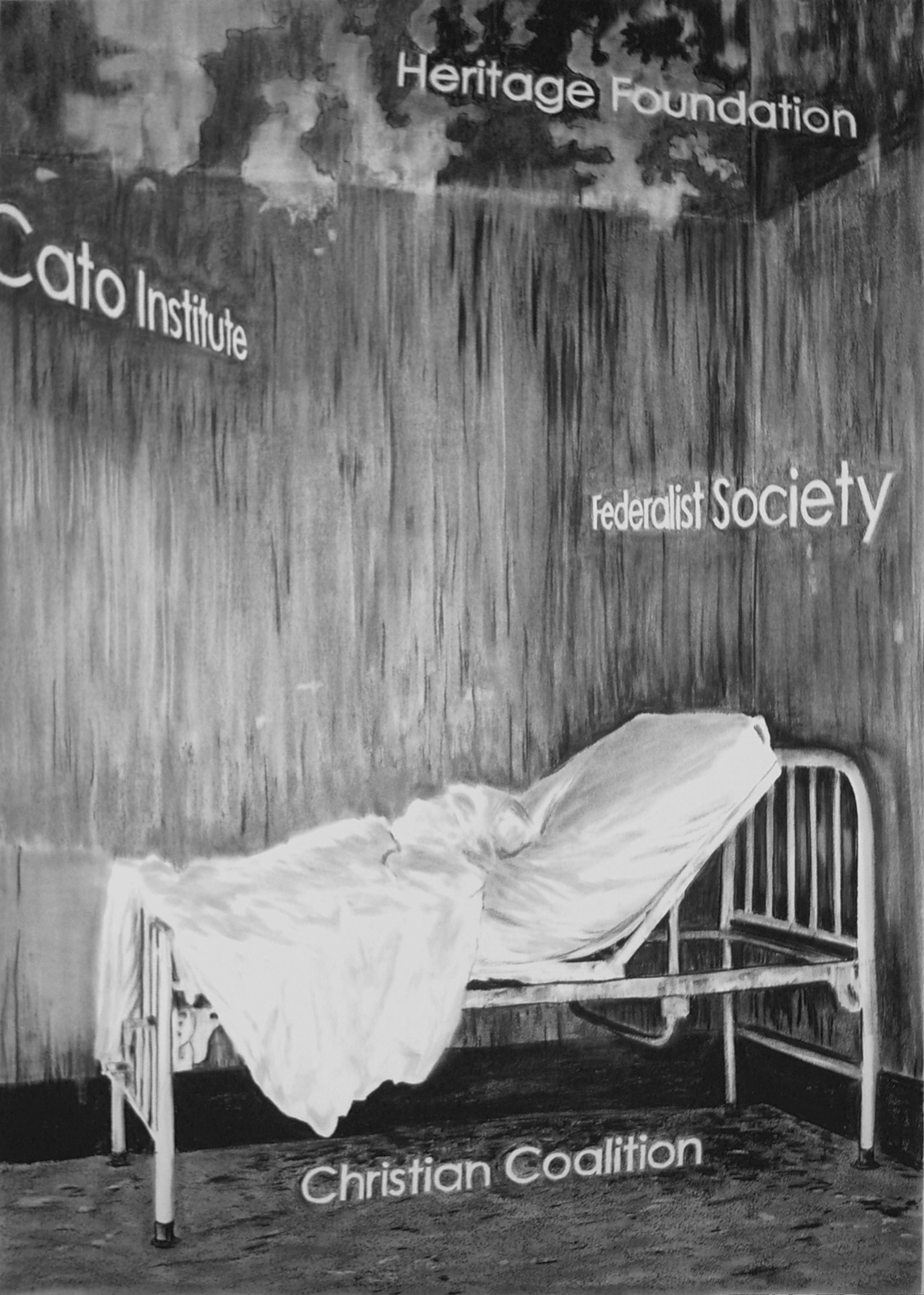

Trevor Guthrie, Death Bed, 2007, charcoal on paper, 100 x 70 cm

Trevor Guthrie, Death Bed, 2007, charcoal on paper, 100 x 70 cm

SW: Your political works tackle figures like Rupert Murdoch with floating perspectival text that recalls Soviet Constructivist graphics. There's a formalist seduction happening alongside the critique.

TG: The political commentary is important. Figures like Murdoch have enormous and unjustifiable power. My wife has a sociology degree, so we have constant discussions about media, literature, and politics. The floating text comes from early twentieth-century Soviet art, probably from the social realism division of Constructivism. Wayne White does similar things now, but a bit differently than what I do.

It's technically challenging, too—blocking out pure white text while applying complicated charcoal around it. If you mess up, you can't erase. But pieces like "Death Bed" feature the names of right-wing think tanks, anti-abortion lobbies. My wife did her thesis on abortion in the media, so her work inspired that particular piece. The formal challenge serves the political message.

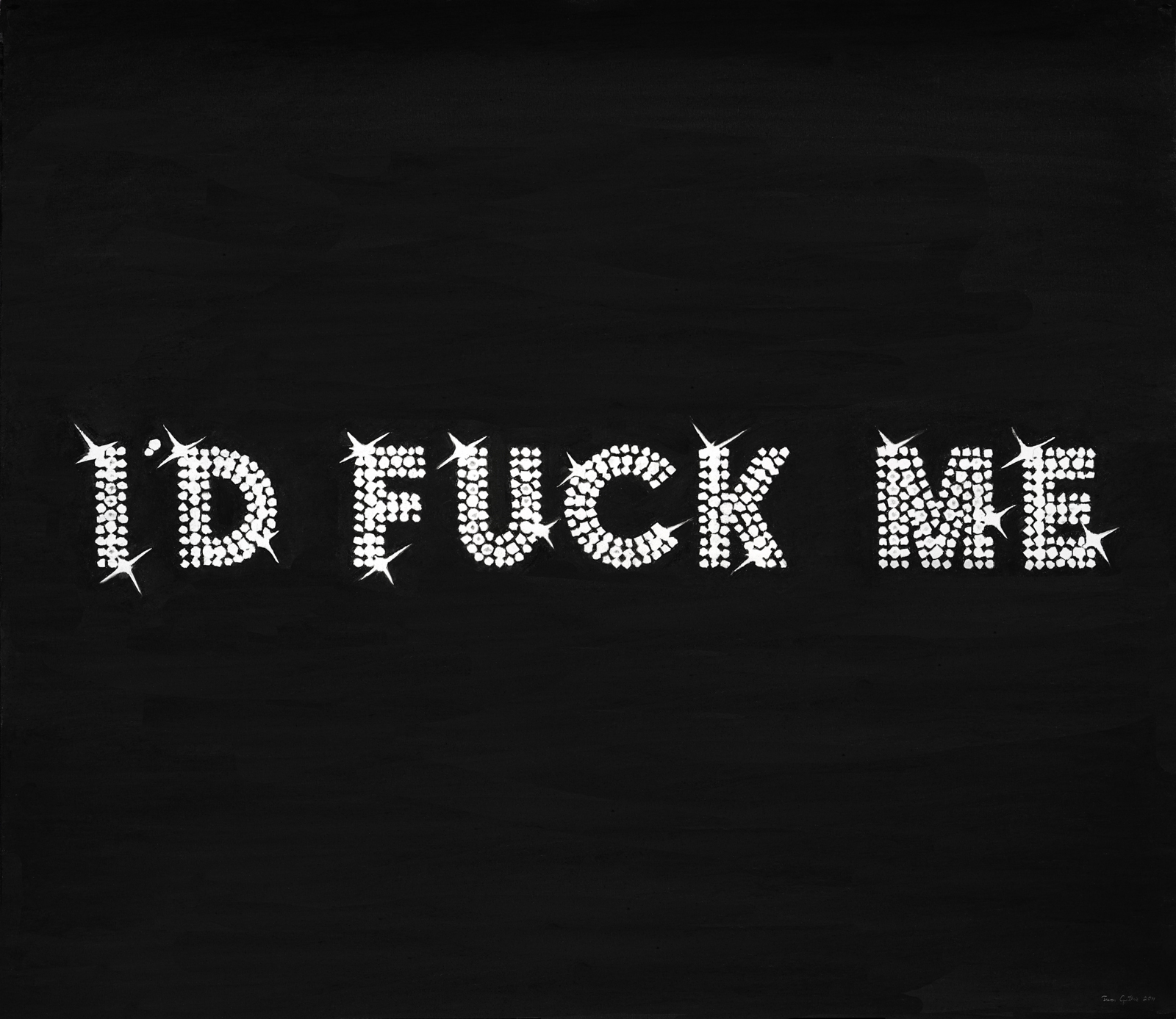

SW: So, the difficulty of the technique becomes part of the work's meaning—the labor-intensive process as a rebuke to easy digital solutions. Let’s talk about another piece, your “Terms of Endearment V” drawing, from 2024. This one made me laugh out loud. It displays the famous quote “I’d Fuck Me” by the serial killer character Buffalo Bill from the classic thriller motion picture Silence of the Lambs.

Trevor Guthrie, Terms of Endearment V, 2024, Charcoal on paper, 52 x 72 cm

Trevor Guthrie, Terms of Endearment V, 2024, Charcoal on paper, 52 x 72 cm

TG: I was messing around with text pieces, sorting through hundreds of fonts, and found this sparkly rhinestone one. I thought, "What's a good phrase to go with this blingy font?" (Laughs) It's a narcissistic term of endearment, of course, but refers to much darker source material. I made the first version in 2011, and it might be my most famous piece. I've done about half a dozen versions over the years.

SW: After twenty years of this practice, what sustains your commitment to this ancient medium in our digital age?

TG: It's honest work. When you're drawing with charcoal on paper, if you fuck up, you can't undo it easily. There's no hiding behind fabricators or factories or studio assistants. It's just me, the charcoal, and the paper—the most direct relationship possible between hand, mind, material, and image.

The art world, like the rest of the consumer world, of course, is obsessed with the next big thing, the latest technology, the most expensive production. But sometimes, the most radical act is to pick up a burnt stick and make a mark on paper, the same way humans have been doing for forty thousand years—until recently. In a world of infinite image reproduction and artificial intelligence, there's something subversive about insisting on the handmade, the singular, the irreproducible.

That's Trevor Guthrie’s small revolt against the machine—one drawing at a time. WM

Stephen Wozniak

Stephen Wozniak is a visual artist, writer, and actor based in Los Angeles. His work has been exhibited in the Bradbury Art Museum, Cameron Art Museum, Leo Castelli Gallery, and Lincoln Center, among others. He has performed principal roles on Star Trek: Enterprise, NCIS: Los Angeles, and the double Emmy Award-nominated Time Machine: Beyond the Da Vinci Code. He is a regular contributing critic for the Observer in New York City and writes essays for noted commercial art galleries and museum exhibition catalogs. He co-hosted the performing arts series Center Stage on KXLU radio in Los Angeles and guest hosts Art World: The Whitehot Magazine of Contemporary Art podcast in New York City. He earned a B.F.A. from Maryland Institute College of Art and attended Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. To learn more, go to: www.stephenwozniakart.com and www.stephenwozniak.com. Follow Stephen on Instagram at @stephenwozniakart and @thestephenwozniak.

view all articles from this author