Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Mannat Gandotra's Outside the possibility of worldly

By CLARE GEMIMA May 29, 2025

At Half Gallery, a quiet but ecstatic turbulence unfolded in Outside the possibility of worldly (May 8–June 3, 2025), Mannat Gandotra’s first solo exhibition in New York. Steeped in improvisation and spiritual intensity, the show summoned vine-like forms, muscular knots, and chromatic ruptures into what Gandotra describes as hybrid spaces of dissonance and devotional chaos. Informed by music, memory, and the stray impressions of city life, she paints towards friction, and allows the unnatural or unresolved to take on a generative force. In this conversation, Gandotra speaks about making space for contradiction, listening to what a painting asks for, and finding where the 'ordinary' begins to unravel.

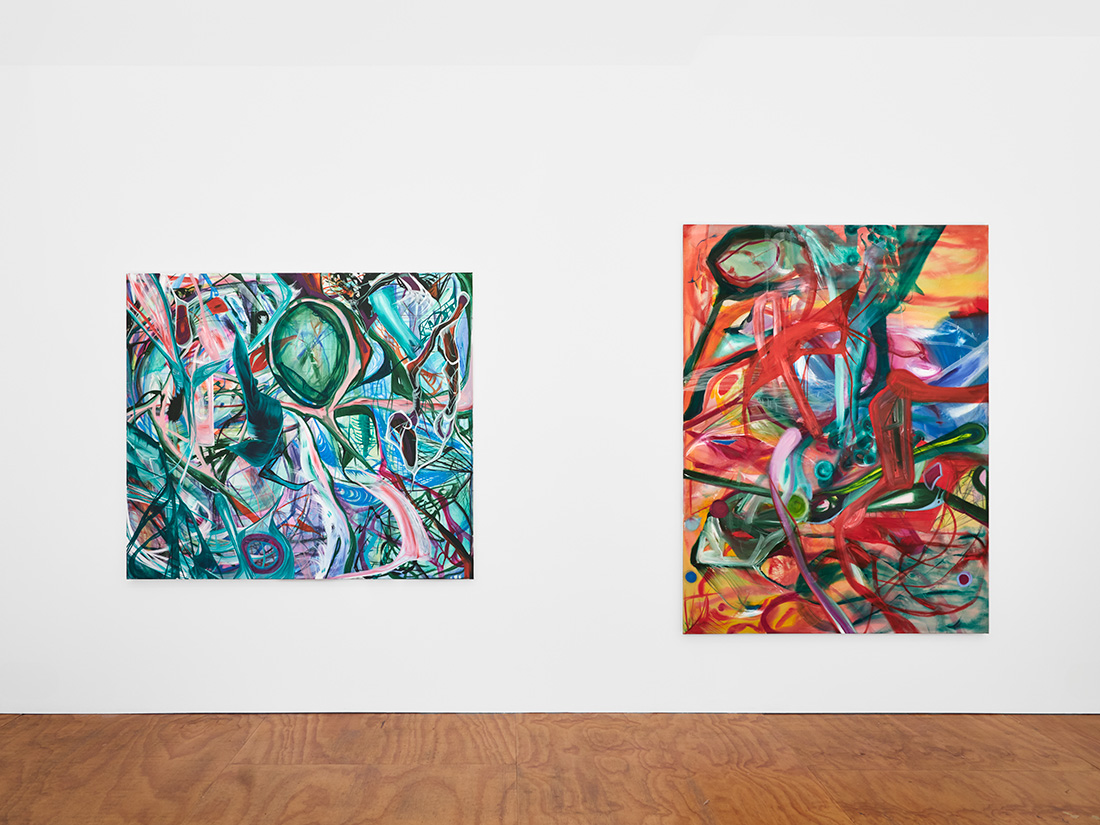

Installation View of Mannat Gandotra’s Outside the possibility of worldly. May 8th - June 3rd, 2025. Half Gallery, New York

Installation View of Mannat Gandotra’s Outside the possibility of worldly. May 8th - June 3rd, 2025. Half Gallery, New York

Clare Gemima: The title of your exhibition, Outside the possibility of worldly, suggests a conscious severing from material or terrestrial logic. What does “worldly” represent for you, and what lies beyond its threshold in your new body of paintings?

Mannat Gandotra: The title came from some rough sketches I had made at home one evening, and the sentence emerged while I was making them. I hung them up in the studio that week, along with the title written on a post-it note. It set the tone for the paintings. It was a lingering thought I kept repeating to myself like a wishful mantra. I believe it was an honest aim to disassociate and dissemble the worldly elements which have subconsciously anchored my work in many ways. My inner desire has been to tap into that space, to step beyond the materiality of paint into something spiritual, incidental, and instinctive. My show’s title summarised my ambition of opening a portal to a new realm–a place that sits outside the possibility of this world.

Clare Gemima: Your works evoke both anatomical interiors and botanical chaos—organs that morph into vines, muscles entangled with canopies. Are these hybrid spaces intended to collapse distinctions between the human and the natural, or is that merely my interpretation?

Mannat Gandotra: While painting, those distinctions are not at the forefront. The questions that come to mind are more so about motion, relationship and flux. Is this form alive and swimming? Is this line residing, flowing or fractured? Is the colour standing armoured, vibrating in joy or shaking in fear? When I apply paint it’s an ignition point, a shock that goes through me that I react to it. It’s every element reacting to each other. I am asking the painting “what do you need?”

Installation View of Mannat Gandotra’s Outside the possibility of worldly. May 8th - June 3rd, 2025. Half Gallery, New York

Installation View of Mannat Gandotra’s Outside the possibility of worldly. May 8th - June 3rd, 2025. Half Gallery, New York

Clare Gemima: Improvisation is central to your process. How do you conceive of rhythm, syncopation, or dissonance in static form, and did you listen to music while you painted your new works?

Mannat Gandotra: John Cage talked about the infinite possibilities of ambient sound. I relate to this by wondering if these infinities can be visual as well. I often ask myself, how does loudness take form in painting? Can it be achieved by increasing the frequencies of colour, line, form, light, or space? During my undergrad, my friend's father was a music professor and introduced me to a book of graphic scores called Notations by Theresa Sauer. I looked at the scores in awe, much like I would’ve a Paul Klee drawing. It was an instrumental moment in realising the physics behind my own paintings and drawings.

There seemed to be many parallels between my process and the open ended interpretation of these scores. A chaotic and haphazard presentation that, upon closer look, revealed such lyrical elegance. While painting, there’s an energetic rhythm–a synchronous motion like a river. This river doesn’t wish to be harmonic nor soft. Its energetic gush is full of a velocity that may overpower rocks on its bed, or create rapids and disruptions. Fragmented friction and fissions emerge. Some paintings feel like wild gardens, where forms are entwined and syncopated whilst being overburdened by beautiful and ugly elements. They are the knots, speed bumps, and rocks. This is the atonal and dissonant part for me. I always listen to music as I’m painting–I can’t paint without it. It sets the tone, quite literally. While painting for this show, I made a playlist called “Sufiyana-Yogi/ Yogic-Sufi” which had a mix of songs from Hindustani classical, Bhakti music, Reggae, Jazz and even some Hawaiian Christian-existential rock. These songs made me feel connected to the cosmic dance. A Basohli miniature painting of Shiva performing the cosmic dance is also the cover of the playlist. I absorb the energies of the songs and enter into a headspace that allows me to plunge into the deep waters.

Clare Gemima: There’s an architectural sensibility to your compositions—often described in terms like gaps, bridges, and speed bumps. Do you consider your paintings to be inhabitable environments, or are they more akin to sentient structures—asserting their own agency, like a garden might?

Mannat Gandotra: My mother is an architect, so I grew up looking at architectural books of monumental temple structures, especially the Khajuraho Temples. They have an overflowing Bosch-like sensibility to them which really influenced me. I often ask myself the question like “could I reside inside?” to decide if a painting is finished. I think of them as habitable environments and portals that summon me in. I desire to be enveloped by them, to have no choice but to dive in. That being said, I do prescribe to the panpsychic thought, where they are sentient and have their own destiny and agency.

[L-R] The Hermit, Upright and Reversed, 2025. Acrylic on canvas. 59 x 67 in. The Sculptor’s Collection of Broken Umbrellas, 2025. Acrylic and charcoal on canvas. 78 x 59 in. Photo courtesy of Half Gallery.

[L-R] The Hermit, Upright and Reversed, 2025. Acrylic on canvas. 59 x 67 in. The Sculptor’s Collection of Broken Umbrellas, 2025. Acrylic and charcoal on canvas. 78 x 59 in. Photo courtesy of Half Gallery.

Clare Gemima: Several of your work’s titles, particularly The Hermit, Upright and Reversed and The Sculptor’s Collection of Broken Umbrellas, seem like riddles or fragments of a larger, unseen narrative. How do they emerge in relation to the paintings, and what function do they serve either for yourself or for your viewers?

Mannat Gandotra: The titles are fragments, glimmers and signals of another space. Spaces and ideas, which come and go while I’m painting, or when the work is finished. I think of titling a piece of artwork akin to naming a child. Their name won't encompass the entirety of their being, rather it’s a gateway to a larger encompassing. The title Sculptor’s Collection of Broken Umbrellas is drawn from my sculptor friend Julia who was my classmate at the Slade. She had this fixation on collecting discarded broken umbrellas after every heavy storm. This feeling of simultaneous collection and collapse was entangled in this painting for me, whereas The Hermit came out of the tarot deck, which I have been learning. I resonate with the hermit card, because I spend a lot of time in isolation while painting. Meditating on this card has offered me a new perspective on my journey. The context of the tarot card changes when it’s upright or reversed. It’s a method I apply to my paintings too, rotating them while painting until the composition unfolds itself.

Clare Gemima: You’ve mentioned collecting corners and “discarded nooks” during your walks through London. How do fleeting impressions of overlooked fragments and urban residue materially inform your practice—and could you elaborate on how this plays out in your process?

Mannat Gandotra: It's a psychic process collecting these visuals, sounds and sights. I think of these as puzzle pieces I’m picking up mentally, holding them in a chamber of my mind and later unpicking them at the studio. It's not a conscious effort to bring them into the paintings. These passion-filled street encounters find a way in. Whether it's a passionate like or dislike, I have no control. A lot of my process is about subconscious unveiling which happens naturally. These collections are cataloged in my body, and come out on their own terms.

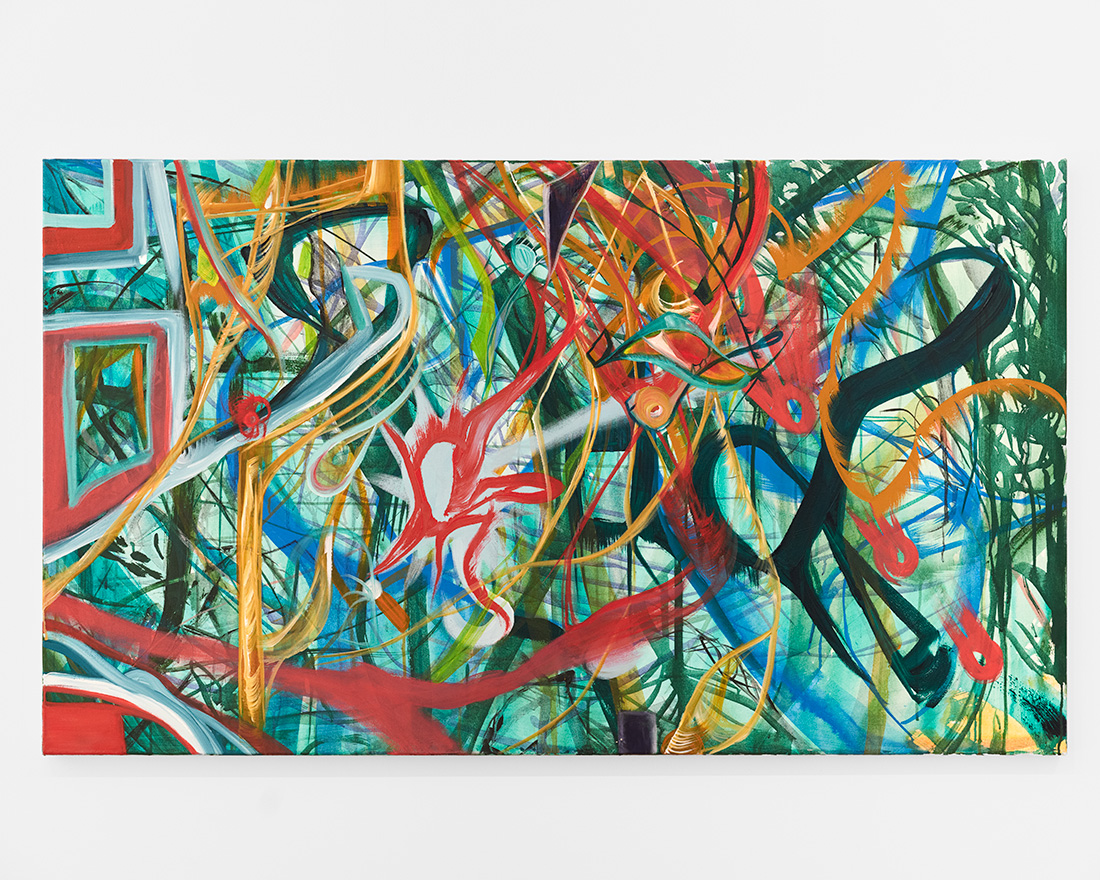

Botanist’s Disguise, 2025. Acrylic on canvas. 16 x 61 in. Photo courtesy of Half Gallery.

Botanist’s Disguise, 2025. Acrylic on canvas. 16 x 61 in. Photo courtesy of Half Gallery.

Clare Gemima: There’s an anti-harmonic quality of your work which resists resolution. Why is dissonance an important principle for you, and do you see it as reflective of a broader philosophical stance? Is it escapism? I am trying to put my finger on it…

Mannat Gandotra: During a tutorial at Slade my late professor Alastair MacKinven spoke to me about how he sees a struggle in my painting. He spoke about how that tension and trouble in resolution is important, and should be celebrated. I stand by this thought. When I think a painting is becoming too easy, I create a barrier, a block, a problem. Having to tackle and reign in the storms keeps me on my toes. This could be throwing in a color I dislike, or something that feels absolutely wrong. It may be unnatural but the painting is in need of it. I also think about how nature is often defiant to symmetry and that in itself is a form of atonality.

Whenever something new comes into my house, I let it sit in a place it doesn’t belong. Toothpaste in the kitchen, vitamins in the living room, a teacup in the bathroom, clothes on an armchair. After days pass by, the objects have marinated, soaked in the environment. They have found a new sense of belonging. I breathe in such dissonance – an off feeling, a type of left-handedness. My paintings are scattered with these essences. They live together, talk, fight, and clash. They speak to each other loudly whether I’m there or not. I don’t think it’s escapism, but rather it is truth seeking. I think of it in how a dancer, who uses their body to improvise their dances, reaches a trance where they release logical control and enter into another space. I imagine the maddening bliss of a master, using their body, sound, or paint which can take even the onlooker to new worlds. To me this is true reality, and at the same time does not feel of this worldly world.

Clare Gemima

view all articles from this author