Whitehot Magazine

November 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

November 2025

Karin Davie: It Comes In Waves at Miles McEnery Gallery - Review by Riad Miah

By RIAD MIAH November 14th, 2025

The Waves of Karin Davie certainly arrive as both a force and a visual experience in her current exhibition at Miles McEnery Gallery. For those who have followed Davie’s practice since the late 1990s, the current paintings here feel like a culmination of several decades spent grappling with the physical and psychological implications of the brushstroke. Throughout her career, color, gesture, and a subtle play between abstraction and representation—between painterly and optical illusion—have formed the connective tissue of her work. These have never been static elements for Davie, but active agents in a continual process of discovery. In this recent body of work, that process becomes a meditation on disruption, tension, and release—on how the painter’s touch can both anchor and destabilize what we see.

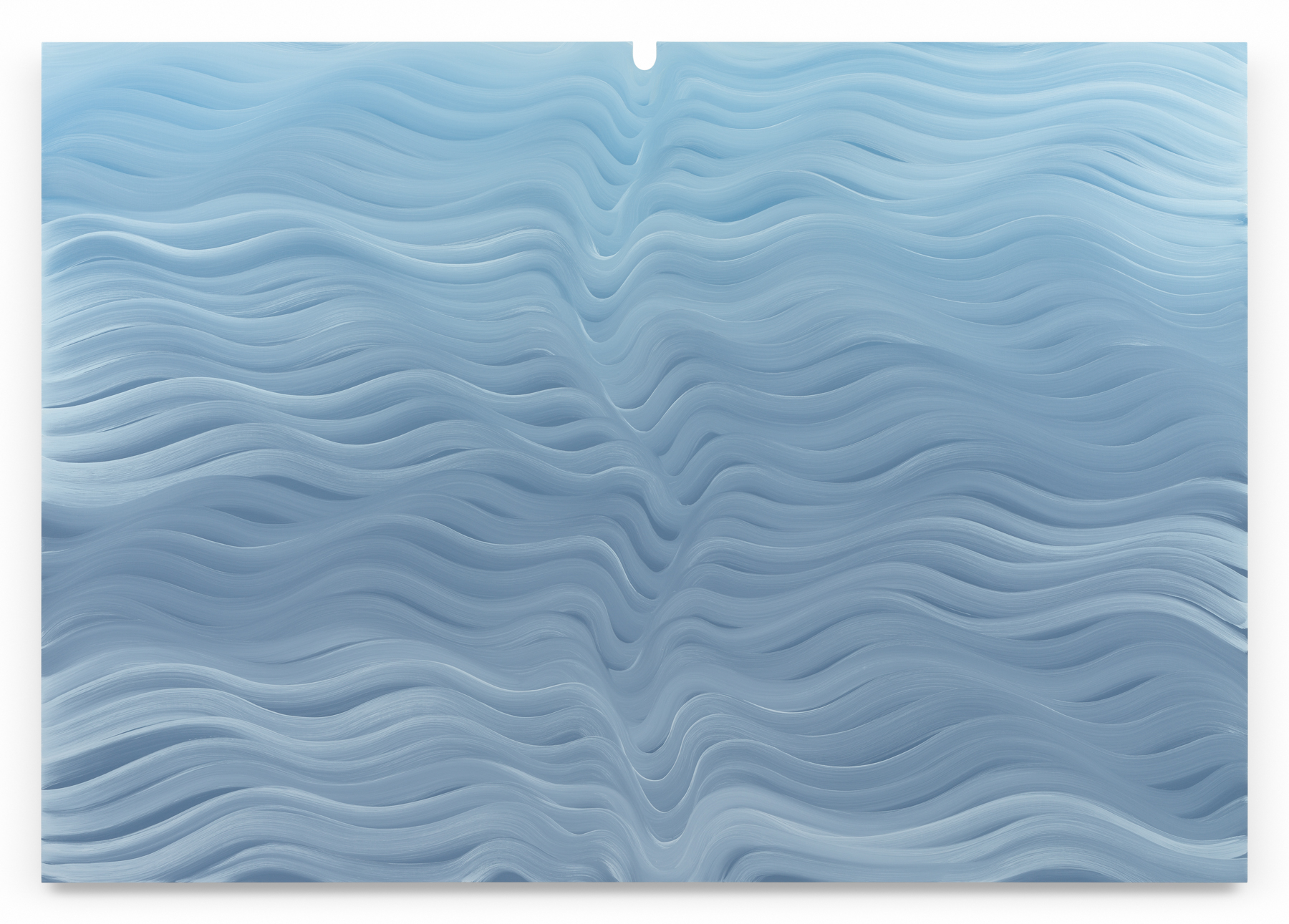

Trespasser no 5, 2025, Oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 60 x 86 inches, 152.4 x 218.4 cm

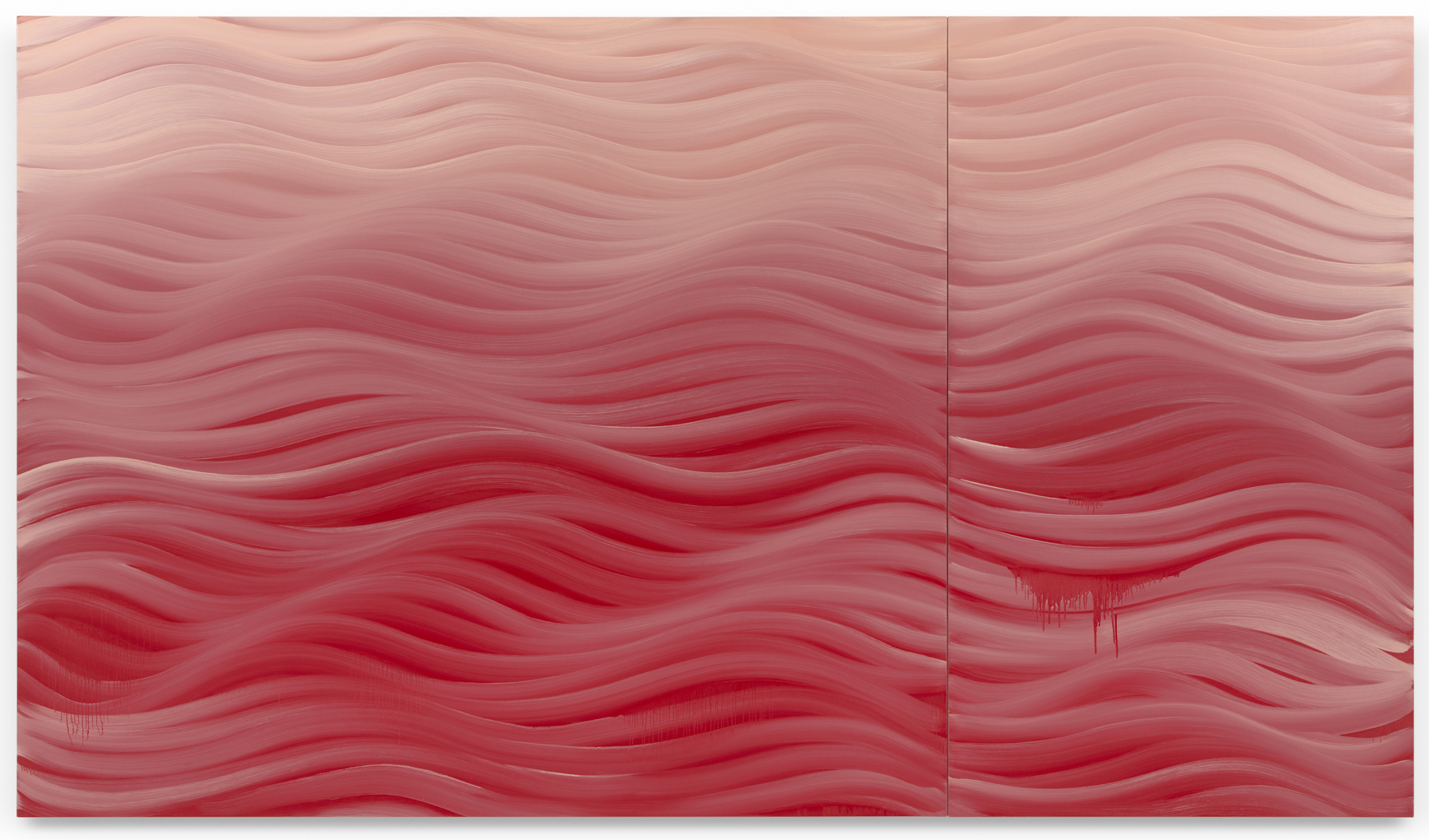

The exhibition comprises eight new paintings, each significant in scale, luminous in color, and characterized by a well-developed rhythm. In six of them, a curved notch is structured at the top edge of the canvas, a formal element that immediately alters how viewers experience the surface. The notch suggests a point of entry, signaling the moment when the painting begins to reveal itself—a rupture that is both structural and symbolic. In two other paintings, “Strange Terrain No. 4” and “Strange Terrain No. 5,” Davie adds a vertical seam that joins two surfaces, simultaneously dividing and uniting the composition. This physical connection subtly shifts perception: the seam appears as a vertical line or break, yet refuses to stabilize the image. In both works, the vertical seam is positioned off-center. As viewers scan the surface, the flowing waves of marks guide the eye to a brief pause, then continue again—not building to a crescendo, but stopping abruptly.

Davie has used the curved notch before, typically placing it at the bottom of the canvas. Reversing its position transforms the psychological weight of the gesture. At the top, the cut out becomes a kind of pressure point—gravity, tension, even a sense of containment bearing down on the gesture waves of paint below. The resulting compositions glide horizontally, their successive bands of color bending and undulating across the picture plane. The rhythm is almost musical, the marks slithering and looping in a measured tempo. Yet within that repetition lies the subtle awareness of collapse—each curve dipping down, hesitating, before straightening and continuing on its way.

Strange Terrain no 5, 2025, Oil on linen, 60 x 105 inches, 152.4 x 266.7 cm

Strange Terrain no 5, 2025, Oil on linen, 60 x 105 inches, 152.4 x 266.7 cm

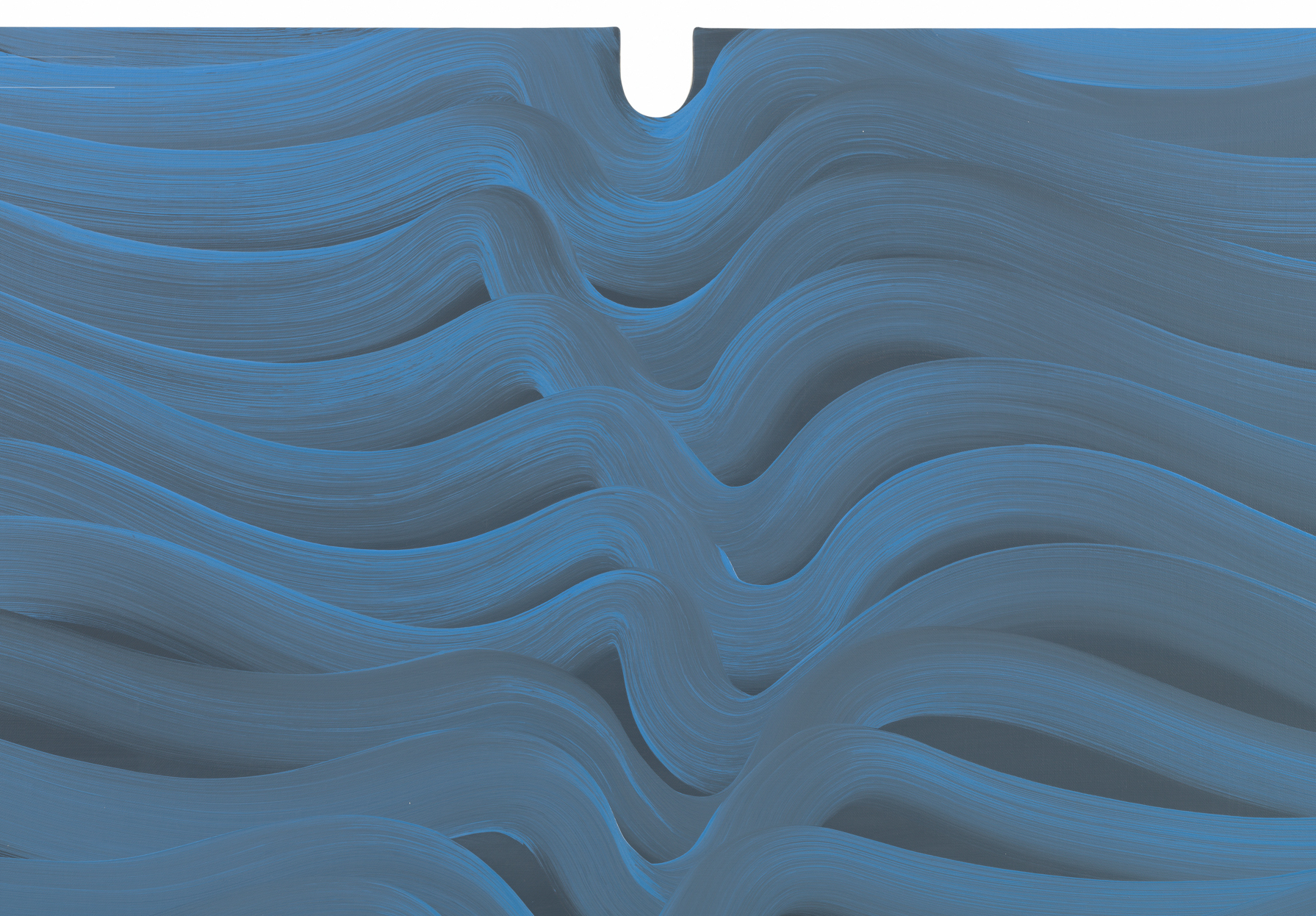

Davie’s brushwork exists in a delicate space between control and surrender, placing her within a long tradition of gestural abstraction. It’s hard not to think of Willem de Kooning, especially his late paintings from the 1970s and 1980s. In those works, de Kooning’s strokes became fluid and nearly transparent, with forms dissolving into ribbons of paint that hovered between figure and background. Davie’s paintings share that sense of movement—an energy caught mid-transformation—but her approach is different. Where de Kooning’s paint is dense, muscular, and fleshy, Davie’s work feels elastic, tensile, and luminous. Her gestures are less about attack and more about absorption. The paint becomes light, folding into itself and radiating outward, as if the surface were breathing.

Light has always been central to Davie’s vision, in fact. Her earlier “Symptomania” series (2000s) depicted illumination from within, as if the canvases were backlit by a screen or digital device—a meditation on how technology has changed perception. Those paintings felt artificial and fevered, with a glow reminiscent of early internet days and late-night TV static. In this recent body of work, however, light becomes natural again, or at least bodily. It no longer seems electrical but organic—sunlight filtered through water, heat shimmering on a surface, reflection bouncing off a mirror. This shift from the technological to the natural marks a quiet yet significant evolution in Davie’s ideas about vision and presence.

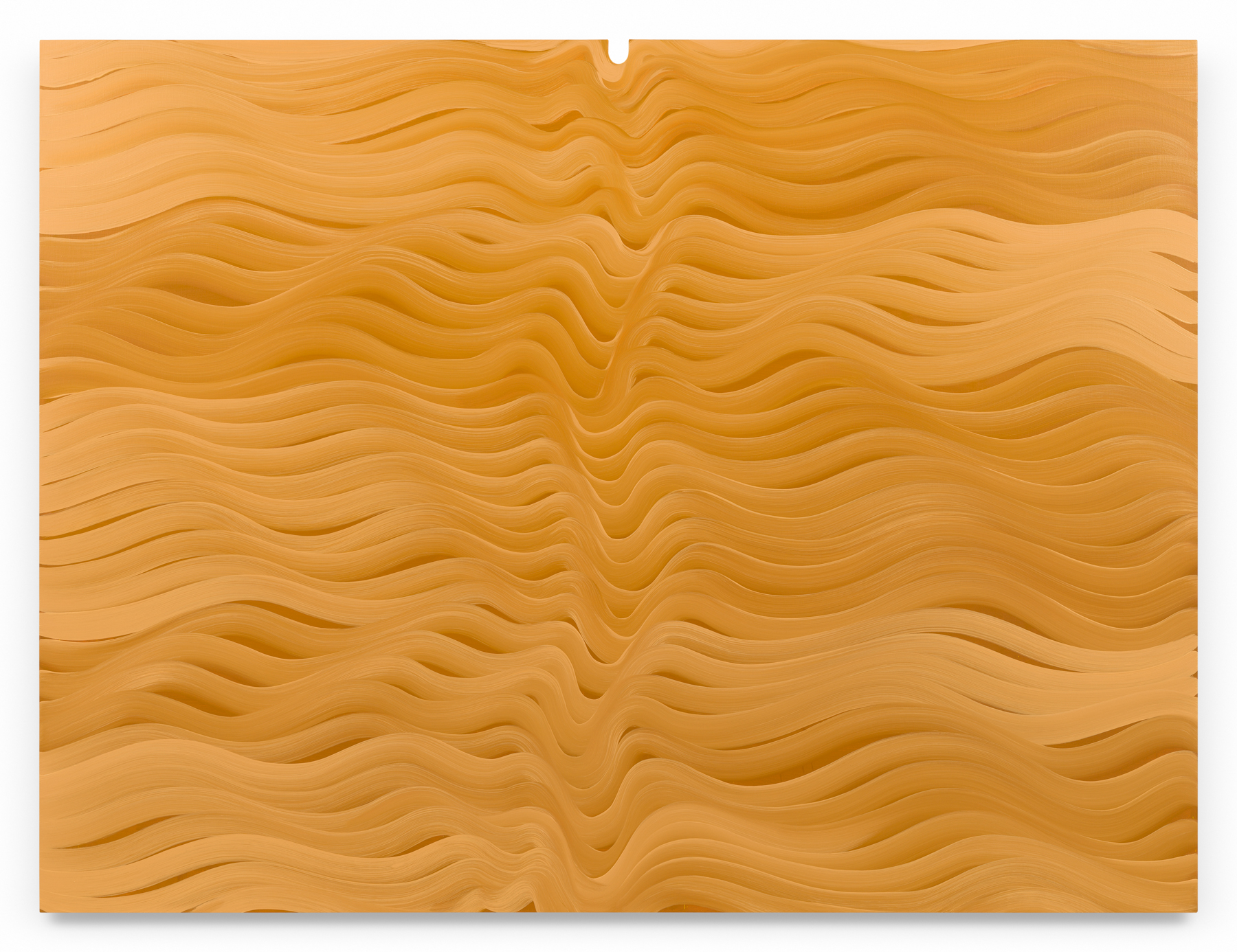

Trespasser no 4, 2025, Oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 72 x 96 inches, 182.9 x 243.8 cm

Trespasser no 4, 2025, Oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 72 x 96 inches, 182.9 x 243.8 cm

The east wall of the gallery displays three canvases in blue, red, and yellow—a clear nod to primary colors. However, these are not pure, optical primaries. Davie deliberately shifts them toward the experiential: the red hints at the tone of a bodily reference, like a healing cut; the yellow evokes the faded warmth of a place once visited, a Tuscan villa or a sunburst at day's end; and the blue hovers between sea and sky, reflective and tangible. Her color choices are grounded in sensation rather than system, making them more personal than theoretical. The effect brings to mind David Reed, whose elongated paintings from the 1980s and 1990s suspended the brushstroke in a cinematic time. Reed’s paint seemed to glow from within, hovering between surface and screen, material and image. Davie shares this fascination with the temporal aspect of gesture—the way a mark can suggest duration, memory, and movement simultaneously. But while Reed’s work felt mediated, cinematically or digitally paused, Davie’s insists on the body. Her strokes are tactile, felt, and elastic; they trace the choreography of the arm as much as the logic of the eye.

Trespasser no 2(detail)

The exhibition engages in a broader conversation about the legacy of postwar abstraction and its reinvention by women painters over the past three decades. Davie belongs to a generation—including artists like Pat Lipsky, Jackie Saccoccio, and Pat Steir—that has aimed to reclaim the gestural as a site of emotional, psychological, and feminist inquiry. Her brushstrokes are never neutral; they pulse with a sense of self-aware sensuality, conscious of their own art-historical lineage. De Kooning’s “woman” paintings linger in the background, but Davie shifts that bodily energy toward abstraction itself. The undulating forms in Davie’s paintings seem less like depictions of bodies and more like embodiments of perception—paint as feeling, as breath, as the visible imprint of thought in motion.

What ultimately distinguishes Davie’s work in this exhibition is her ability to balance rigor and sensuality, intellect and intuition. The paintings evoke a bodily response—the viewer feels the rhythm of the waves, the pull of gravity, the shimmer of light—but they also operate conceptually as meditations on what it means to paint today. The notched edges and seams remind us that the painting is a constructed object, not just a window. They puncture illusion even as they create it.

Trespasser no 1 (Small), 2025, Oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 40 x 32 inches, 101.6 x 81.3 cm

Trespasser no 1 (Small), 2025, Oil on linen over shaped stretcher, 40 x 32 inches, 101.6 x 81.3 cm

In her work, Davie does not just depict motion; she brings it to life. Her paintings remind us that abstraction isn't a rejection of reality but a way to engage with its fluid and unstable nature. For Davie, the gesture remains both a space of freedom and discipline—a way to find the self within the ongoing turbulence of seeing and feeling. As de Kooning once said, “Flesh was the reason oil paint was invented.” Davie carries that idea into the twenty-first century, suggesting that light—and its luminous expression in color—may be the reason painting still matters.

Riad Miah

Riad Miah was born in Trinidad and lives and works in New York City. His work has been exhibited at the Baltimore Museum of Contemporary Art, Sperone Westwater, White Box Gallery, Deluxe Projects, Rooster Contemporary Art, Simon Gallery, and Lesley Heller Workshop. He has received fellowships nationally and internationally. His works are included in private, university, and corporate collections. He contributes to Two Coats of Paint, the Brooklyn Rail, and Art Savvvy.

view all articles from this author