Whitehot Magazine

September 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

September 2025

Donald Kuspit on The New Surrealism

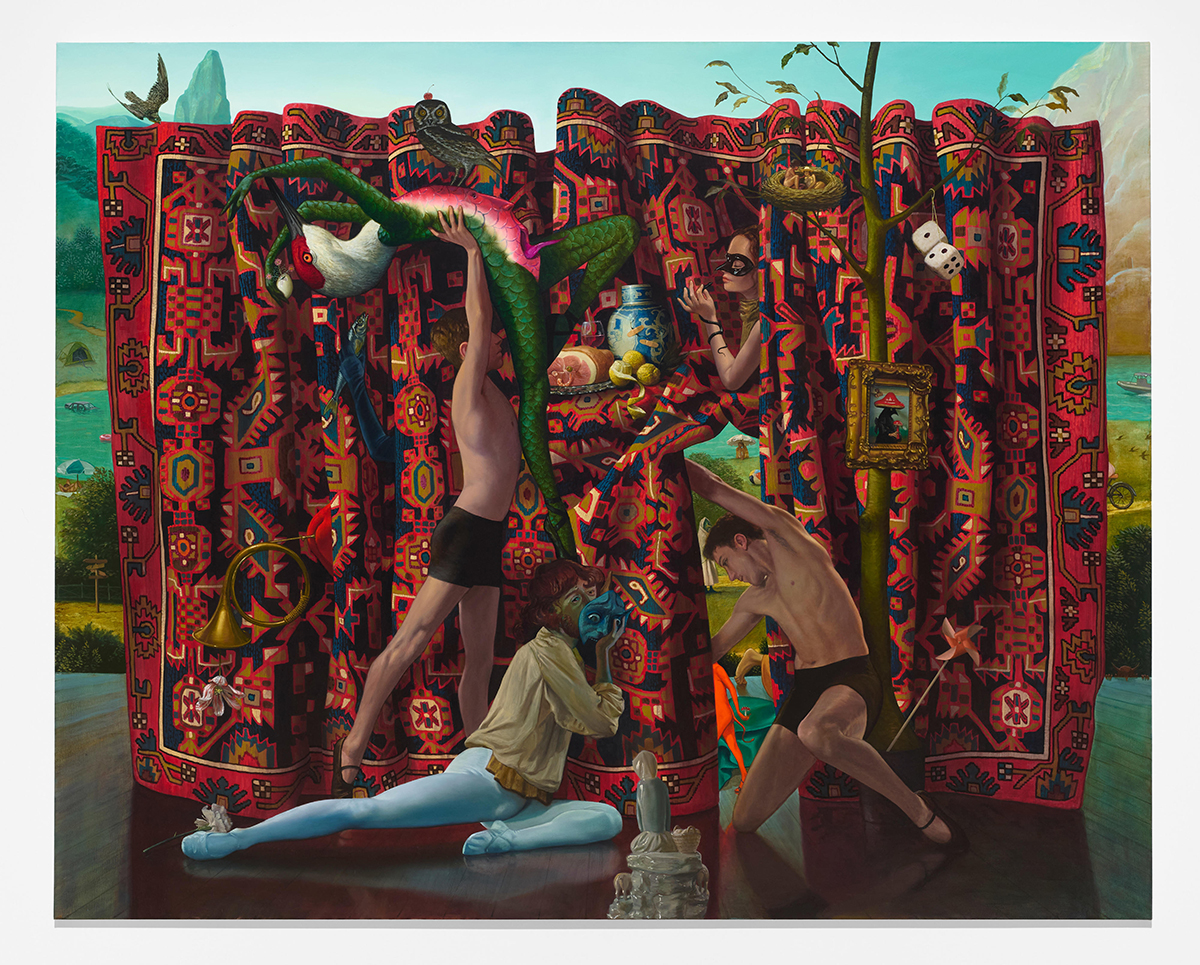

Matt Hansel, A Dance With The Past, 2025, Oil on linen, 142.2 x 177.8 cm (56 x 70 in)

Matt Hansel, A Dance With The Past, 2025, Oil on linen, 142.2 x 177.8 cm (56 x 70 in)

By DONALD KUSPIT June 9, 2025

Robert Zeller, a master of figurative painting and a Surrealism-inspired painter, has curated an exhibition of contemporary Surrealist painting for Robilant + Voena, a gallery known for exhibiting the works of Caravaggesque artists. Caravaggio’s realism has been said to be surreal by reason of its tenebrism, extreme contrasts of light and dark, implicitly the conscious and the unconscious, going back to Plato’s myth of the cave. Caravaggio’s realism has what Andre Breton called the “very high degree of immediate absurdity” that characterizes surrealism. “Pure psychic automatism”—the French psychologist Pierre Janet’s concept—involving abandoning “all control exercised by reason and outside all aesthetic or moral preoccupations”—is the means to the “disinterested play of thought” evident in dreams. Zeller believes “that Surrealism, and its fore-bearer Dada, while no longer formal movements, are currently the most influential visual languages spoken in contemporary art.” The exhibition includes masterpieces by four “canonical, historical Surrealists, Leonor Fini, Leonora Carrington, Yves Tanguy and Giorgio De Chirico” along with the “dream works” of 17 contemporary artists. The exhibition invites one to compare the canonical masters and the new masters—neo-Surrealists, as it were—which I will not do, even casually, for the cultural and social contexts in which they worked is fundamentally different. The Old Surrealism developed in the aftermath of the trauma of World War I—the first Surrealist Manifesto appeared in 1924, six years after the war ended—while the New Surrealism developed in response to the banalization of abstract art—“zombie formalism,” as Walter Robinson described it—and the banal aesthetics and mindlessness of popular mass culture. It lacks the uncanny subtlety of Surrealism.

Alessandro Keegan Vital Force, 2024, Oil on canvas, 177.8 x 152.4 cm (70 x 60 in.)

Alessandro Keegan Vital Force, 2024, Oil on canvas, 177.8 x 152.4 cm (70 x 60 in.)

But I will argue that while original Surrealism was a response to the disillusionment that followed World War I—Breton (1896-1966) was conscripted into the French army, interrupting his medical school studies, where he focused on mental illness—the new Surrealism is a response to what Jose Ortega y Gasset called “the dehumanization of art,” evident in nonrepresentational artists determined to escape realism and romanticism. Conceptual art completes the escape. One might say that the contemporary surrealists in the exhibition are neo-romantics, to the extent that feeling matters for them more than form, the form of such works as Maria Kreyn’s Life on Jupiter, 2025 being peculiarly indeterminate, as the mix of incommensurate forms at the bottom of the painting indicates, along with the formless cloudy atmosphere. The sense of isolation and abandonment, conveying subliminal, incurable suffering in Robert Ryan’s Night Watch, The Long Conversation, and Limbo, all 2025—romantic masterpieces, reminding us that Surrealism is rooted in Romanticism, for feeling is all in Romanticism, as Baudelaire said, even as the loneliness of the figures suggests the existential character of the new surrealism, in contrast to the psychoanalytic aspect of the old surrealism. Loneliness involves a state of abandonment, Hannah Arendt argued, involving the feeling of the meaninglessness of existence, and with that a loss of self-identity. To my mind’s eye, this suggests the difference between the old and new surrealism: the works of the former are more like daydreams, of the latter like nightmares, as Matt Hansel’s A Dance With The Past, 2025 seems to be. The young upright male figure holding a dragon overhead in triumph—an allusion to St. George--and the male figure going through an opening in the hanging carpet into what seems to be a paradise—not without its devils, as the red figure with a tail seems to be—are in effect the same person, as the fact that they are both naked apart from the black shorts they wear. A beautiful masked woman, her eyes closed, nonetheless seems to be looking at a small black snake wrapped around her right arm. The reclining young man—all the figures are young and ageless—wearing blue tights holds a grim blue mask to his face. The work is rich with allegorical symbols, many familiar from Flemish and Dutch still life painting. Among them, hanging from a thin tree, is a pair of dice adding up to lucky seven. All the figures are young, the artifacts traditional, reminding us that many Old Master works are peculiarly surreal, by reason of their allusion to such myths as St. George and the Dragon, and to religious fantasies in general, the gods being inherently surreal. The work reminds us that surrealism is deeply rooted in symbolism as well as romanticism.

Lola Gil, Woman, 2025, Oil and acrylic on linen, 75 x 120 cm (29 1/2 x 47 1/4 in.)

Lola Gil, Woman, 2025, Oil and acrylic on linen, 75 x 120 cm (29 1/2 x 47 1/4 in.)

To my mind’s eye the key to Arghavan Khosravi’s The Gates, 2025 is the black ooze—black death--dripping from the canvas and the faceless females—one with her chin held up by her hand, the traditional pose of melancholy. The huge work, 98 ½ x 136 x 10 inches, a tour de force, is fraught with contradictions, epitomized by the difference between the free-floating hands and the hands of the female figures and the flourishing and desiccated plants. “The dream can also be used in solving the fundamental questions of life,” Breton writes, and of death, as the black ooze that drips from the painting into the viewer’s world, intimidating her into awareness of death, an awareness already implicit in the melancholy muse in Khosravi’s masterpiece.

Vincent Desiderio, Study for Dead White, 2019, Oil on linen, 121.9 x 243.8 cm (48 x 96 in.)

Vincent Desiderio, Study for Dead White, 2019, Oil on linen, 121.9 x 243.8 cm (48 x 96 in.)

Jamie Adams’ exquisitely descriptive paintings of the peculiarly androgynous actress Jean Seborg, both 2022—in Jeannie Rose she’s clearly female, as her flat panties and bulging thighs imply, and in Jeannie Pink Chair, as the phallic tie she wears, she’s implicitly male—carry the surrealistic fascination with perversity, especially sexual perversity, to an ironical extreme. The general meaning of perversity is twisted, distorted, improper—a psychoanalyst regards it as the erotic form of hatred--suggesting that Adams’ fascination with Seborg masks his disillusion with her, for she traps him between the Scylla of heterosexuality and the Charybdis of homosexuality. Surrealism tends to be dialectical, the opposites usually unresolved, conveying emotional conflict.

Installation shot of exhibition in R+V NYC, featuring (L to R) Jamie Adams, Jeannie Pink Chair, 2022, Oil on linen, 91.4 x 81.3 cm (36 x 32in)

Installation shot of exhibition in R+V NYC, featuring (L to R) Jamie Adams, Jeannie Pink Chair, 2022, Oil on linen, 91.4 x 81.3 cm (36 x 32in)

Jamie Adams, Jeannie Rose 2022, Oil on linen, 114.3 x 76.2 cm (45 x 30 in.)

Laura Krifka, Smile, 2024, Oil on canvas, 91.4 x 91.4 cm (36 x 36 in.)

In Laura Krifka’s Smile, 2024 a pregnant woman with a C-section scar grips the arms of an armchair as she turns away from the spectator, her face in shadow. Behind her, on a window, is a grid, with a schematic rendering of grinning red lips and clenched teeth, in effect the face of a joker in schematic form. In the marvelously paradoxical Nip, 2024 the nipple of a fleshy rounded breast is at odds with the bright red lips of a mocking joker’s mouth. The works are radically feminist. “Krifka finds it insulting for women to be told to smile all the time, when they have to “hold it together” even as horrific things happen to them on a physical, mental and societal level…She believes that motherhood in contemporary culture is a world flipped upside down, that women get eaten up, consumed by the child they are inside, as well as children already born, and everyone and everything else.” It is rare to find such bitterness, feminist or otherwise, epitomized in art.

Nicola Verlato’s Kurtz, 2018 is a white portrait bust of Marlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz in Francis Coppola’s film Apocalypse Now. Brando-Kurtz’s head is surrounded by a ring of baby teeth and has a diamond in its forehead, alluding to Brando-Kurtz’s being shot with a diamond bullet through his forehead. The head is digitally sculpted, and as such uncannily perfect. Brando-Kurtz has been idealized, purified of his life as a soldier in the Special Forces. Verlato clearly identifies with Kurtz, implying that the portrait bust is a symbolic self-portrait of the artist who created it. “A diamond bullet right through my forehead” is an inspiration. Velato is “the genius” with “the will to do that”—make the “perfect, genuine, complete, crystalline, pure” portrait bust. Much surrealist art has been made by self-congratulating genius, among them Salvador Dali and Max Ernst.

Arghavan Khosravi, The Gates 2025, Acrylic on canvas and wood panel, chain and found

Arghavan Khosravi, The Gates 2025, Acrylic on canvas and wood panel, chain and found

metal keys, approx. 250.2 x 345.4 x 25.4 cm (98 1/2 x 136 x 10

Noorain Inam’s rather crowded, folklore, loosely painted, expressively messy Psychophony—the myth of birds carrying the souls of someone who passed on and is being heard in their caw, 2025—is the antithesis of Verlato’s perfectionist masterpiece Kurtz. But Inam’s painting has its surrealist virtues: it is a kind of fantasy of a primordial world. It is childlike, but the hand carvings of birds and horses and hands on the Rosewood frame are primitive masterpieces based on a careful observation of nature, in contrast to the toylike objects in the painting. Inam grew up in Pakistan; “her grandmother used to tell her stories about animals she met along the way before picking Inam up from school.” They are implicitly fairytales, like Inam’s crowded picture, a sort of expressionist rendering of the creatures in these stories, reminding us that fairy tales are a staple of Surrealism, as Max Ernst’s Une Semaine de Bonte makes clear.

The surrealism in Lars Elling’s Rite of Passage, 2025 exists in the tension between the realistic representation of the boy being vaccinated by a nurse in the foreground and the shadowy fantasy of a boy on a white horse in the background. The work is part of the section of the exhibition devoted to “The Psychic Interior,” but Ginny Casey’s Overgrown Vessel, 2025 is more obviously emblematic of a psychic interior and a woman’s womb—the blue vessel with legs in 2nd Generation, 2025 with water pouring into it from the faucet of a breast-like pitcher held—squeezed?—by a woman’s hand. Lola Gil’s Woman, 2025 shows us, among other images, a woman’s face, repeated implicitly infinitely, overlaid by a yellow ghost-like female figure, in a kind of rustic space, as the chimney built of stones and the cactus suggest. In sharp contrast, Tim Kent’s Winter Studio, 2025 is a grand space with grand paintings on the wall, blurred into shadowy elegance. The work the artist is painting —presumably a portrait of the model sitting on the edge of the bed and getting dressed after posing naked—looks more like an abstraction than a portrait. The work reminds me of Picasso’s Painter and Model Knitting, 1927. The painter and the model are realistic; the painting of the model is a complex geometrical abstraction. The contradiction is surreal by reason of its unresolvability.

Lars Elling, Rite of Passage, 2025, Egg oil tempera on canvas, 200 x 165 cm (78 3/4 x 65 in)

Lars Elling, Rite of Passage, 2025, Egg oil tempera on canvas, 200 x 165 cm (78 3/4 x 65 in)

The “Non-Objective Fragments” are sometimes fraught with enigmatic fantasy, as in Alessandro Keegan’s Through Primal Eyes, 2024, sometimes mesmerizingly all over, as in the nuanced colors of Kristy Luck’s Untitled paintings, 2024, sometimes fraught with eccentrically biomorphic forms, as in Alicia Adamerovich’s Inflated, 2025. Adamerovich also has the distinction of creating Nimrod, 2024, a sculpture whose base is a tree stump, whose peak is recycled wood. A white testicular-like form hangs in the opening in the stump. Nimrod founded Babylon the Great, a pagan center of state-sponsored worship, involving human sacrifice, and built the Tower of Babel in defiance of God. Nimrod’s absurd construction gives it surreal credentials, but perhaps more importantly it is an attack on patriarchy. Many of the works by female artists are ideologically motivated—feminist, sometimes unhappy with woman’s lot in nature, motherhood, as well as society, in which she is implicitly an outsider, as the females in Khosravi’s The Gates are. Perhaps the most important aspect of the New Surrealism is the number of brilliant women artists, their remarkable creativity testifying to the feminist revolution, It is worth noting that the original members of Breton’s group of Surrealist artists had 22 men and two women—Gala Eluard and Dora Maar—and of Zeller’s group of 17 Neo-Surrealist artists I have addressed the work of 6 men and 7 women. Breton was prejudiced against women artists. His attitude is epitomized by Giacometti’s Woman With Her Throat Cut, 1932; it epitomizes the traditional male Surrealist attitude to woman. In Jamie Adams’ paintings of Jean Seberg she is intact, a shapely whole figure, rather than the misshapen surreal monster that is Picasso’s misogynist Grand Nu au fauteuil rouge,1929. WM

Donald Kuspit

Donald Kuspit is one of America’s most distinguished art critics. In 1983 he received the prestigious Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinction in Art Criticism, given by the College Art Association. In 1993 he received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Davidson College, in 1996 from the San Francisco Art Institute, and in 2007 from the New York Academy of Art. In 1997 the National Association of the Schools of Art and Design presented him with a Citation for Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts. In 1998 he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2000 he delivered the Getty Lectures at the University of Southern California. In 2005 he was the Robertson Fellow at the University of Glasgow. In 2008 he received the Tenth Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. In 2013 he received the First Annual Award for Excellence in Art Criticism from the Gabarron Foundation. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Fulbright Commission, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim Foundation, and Asian Cultural Council, among other organizations.

view all articles from this author