Whitehot Magazine

October 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

October 2025

“Queer art feels like world-building:” A conversation with Davy Pittoors about Queeriosities 2025

Killburn (2025), by Krzysztof Stryzelecki. Copyright held by the artist.

Killburn (2025), by Krzysztof Stryzelecki. Copyright held by the artist.

By EMMA CIESLIK September 26th, 2025

Today, the fourth annual Queeriosities opened at Copeland Gallery in Peckham, South London. Founded in 2023, Queeriosities is an arts and makers fair for queer and trans creatives and features the work of over 60 LGBTQIA+ artists, makers, and small businesses. Attendees at the event can purchase the art of many queer artists, including new artists like Emily Witham, Ross Head, and Traf_Algar — alongside repeat favorites like Richard Kilroy, The Common Press, An Nguyen, Oli Raptor, and Lily Deason, participate in public programming, and enjoy informal spaces to gather and connect as an LGBTQIA+ community.

At the center of this queer marketplace is the exhibition We Come to This Place for Magic, showcasing the painting, ceramic, and mixed media work of Paul Majek, Devynn Barnes, Theo Dunne, Krzysztof Strzelecki, Marf Summers and Lawrence Cuevas. As someone deeply fascinating in the history of queer and trans world-building, I reached out to Davy Pittoors, an independent curator, arts organizer, and creative director who founded Queeriosities and curated We Come to This Place for Magic.

Although originally from Belgium, he has worked in the UK since 2007, and as he shared with me, his “practice explores queer belonging and home-making by deliberately blurring the lines between art and craft, gallery and home, and archive and collection.” In our conversation, Pittoor highlighted the importance of queer collecting and community making, as well as the magic of becoming and celebrating who we are.

The rhythm of our conjure (2024), by Devynn Barnes. Copyright held by the artist.

Cieslik: What motivated the creation of a queer and trans art market, and what is its importance today?

Pittoors: We’re living in frightening times for queer people — especially for trans and non-binary members of our community. That climate takes a toll. I’ve always felt that queer artists and craftspeople are among the bravest and most resilient voices we have, but the anxiety of the world around us demands so much energy that simply working and living can become exhausting. Some double down, making sure their perspectives aren’t lost. Others step away from their practice to focus on direct activism. All need space for self-care and for community care.

That’s part of why Queeriosities matters to me. It’s not just a fair but a space for queer art, queer craft, queer expression, and queer connection. By creating a dedicated queer marketplace, we’re also providing direct economic opportunity — a platform where artists can present their work with confidence, meet audiences who understand and value it, and sustain their practice on their own terms. Again and again, artists tell me how safe they feel at the fair. Being surrounded by other queer artists, while selling to an all-queer audience, creates room to breathe — a space to exhale.

And the most rewarding thing has been watching what happens beyond the weekend itself: friendships, collaborations, and whole new projects that take root through connections made at Queeriosities. It’s proof that a fair can be both a marketplace and a community, sustaining queer life in the present while helping to imagine new futures.

Cieslik: How did the grounding exhibition We Come to This Place for Magic come into being?

Pittoors: My curatorial process is very relational by design — and it begins organically: over the course of the year, a theme emerges through conversations, research, and observation. I then bring that theme to artists and invite them to respond. From there, it’s about trust — I give them free rein to interpret and create in whatever way feels true to their practice. I’m not interested in dictating what an artist should make; the creativity lies in how they bring their perspective to the table. And when those works come together, the exhibition becomes about the surprising echoes and contrasts that emerge between them.

Last year’s exhibition, Wendy Houses, explored queer domesticity through artists working in miniature, dollhouse-like forms. This year’s show, We Come to This Place for Magic, expands that curiosity to ask how queer people build and shape the world around them. It features six bold artists — Paul Majek (he/him), Devynn Barnes (she/her), Theo Dunne (they/them), Krzysztof Strzelecki (he/him), Marf Summers (they/them), and a debut by Lawrence Cuevas (he/him). Together their work spans painting, sculpture, ceramics, and installation, offering deeply personal responses to the idea that queer world-building functions not as fantasy but as survival — and as evidence of other lives already in motion.

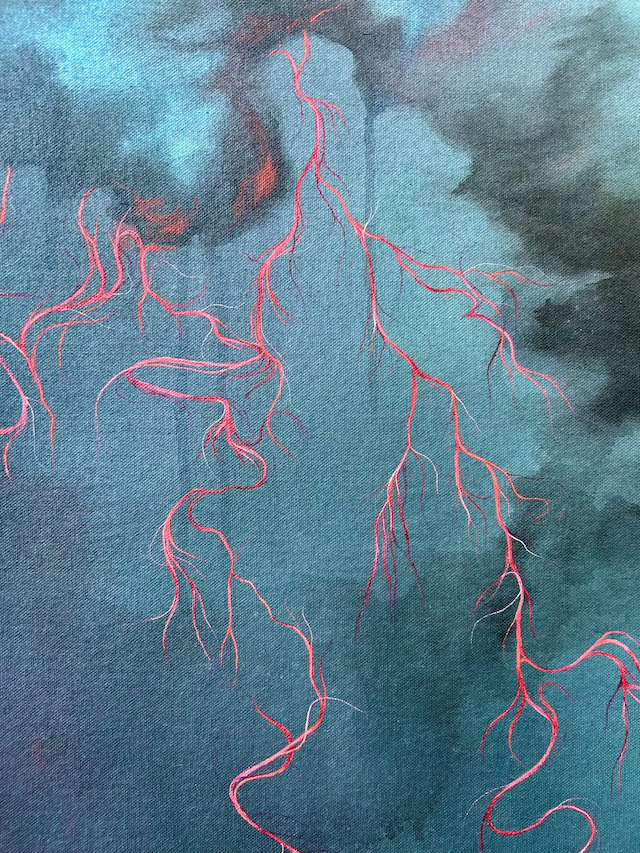

Detail from DEEPER! DEEPER! SYMPATHIES (2025), by Marf Summers. Copyright held by the artist.

Cieslik: What is the potential and power of queer and trans magic? How are we ourselves magical?

Pittoors: Queer and trans magic is the ability to create something out of nothing — to transform inhospitable ground into a site of connection, joy, and possibility. For many of us, magic isn’t an abstract metaphor but a lived skill: flicking a switch in a space, with a look or gesture, and suddenly it becomes ours; shapeshifting between contexts and even, quite literally, transforming our bodies. We carry the power to collapse boundaries not just between gender, but between past and present, domestic and external, grief and joy. That’s why so much queer art feels like world-building — it refuses limits, and instead makes portals where history, imagination, and our own bodies meet. The magic is that we’ve always done this, even in the hardest conditions: re-making homes, languages, kinship, and futures that others said were impossible.

Detail from Overture (2025), by Theo Dunne. Copyright held by the artist.

Cieslik: What is the power of creating and maintaining a safe space for trans people and trans visibility?

Pittoors: A safe space for trans people isn’t neutral — it’s transformative. At a time when trans lives are under constant scrutiny and attack, spaces that are explicitly safe counteract the erosion of rights and the weaponisation of visibility. They ensure that trans people can gather, create, and be seen on their own terms, without fear. It allows trans artists and audiences to show up whole, without shrinking themselves, and to be mirrored back with care and celebration. Visibility alone can be precarious; what matters is visibility grounded in safety, so that expression doesn’t come at the cost of vulnerability. Within Queeriosities, that means making room where trans makers can share their work and know it will be received with respect, where their presence shapes the atmosphere rather than being tolerated by it. The ripple effect is huge: safety makes risk possible, and risk is where the most vital art is born. It’s not only about protection, but about opening the conditions for expression, connection and thriving.

The recent TRANSCESTRY anniversary show by the Museum of Transology was a masterful example of this — and we strive to create that kind of space with Queeriosities as well.

Cieslik: How did you meet the artists involved in the show, and what motivated their interest in contributing?

Pittoors: First, there are the 60+ exhibiting artists, selected through an open call. I always look for a balance of craft, quality of output, and a strong story or ethos behind the work. It’s never just about aesthetics — it’s about conviction and lived experience. That approach makes the fair floor feel both diverse and cohesive, and it reflects something fundamental: the queer community is vast, complex, and messy. Working closely with artists across all its intersections brings that reality into view in ways that feel both exciting and refreshing.

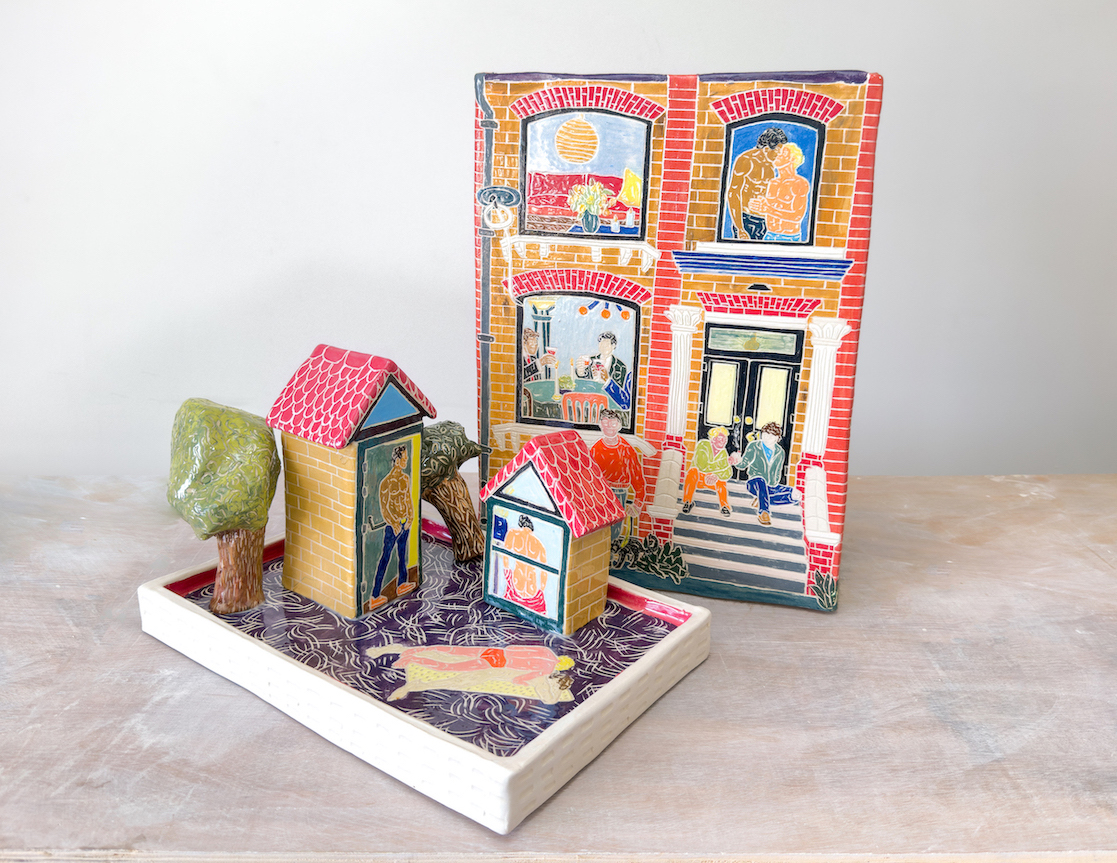

The artists in this year’s exhibition came to me in very different ways. Theo Dunne was a past Queeriosities exhibitor whose work I had long admired. I first connected with Marf Summers when I photographed their home for an essay in A Great Gay Book. I encountered Devynn Barnes’s practice at their debut show at Schlomer Haus Gallery in San Francisco; and similarly while I was aware of Krzysztof Strzelecki’s work, I saw them in person for the first time at his recent show at at Anat Ebgi in New York, where his apartment pieces and urinal sculptures really expanded how I was thinking about queer world-building. Paul Majek I discovered more recently at the Royal Drawing School, and his past mixed-media work really struck me.

And then there’s Lawrence Cuevas, whose story feels almost fated. I was walking down Folsom Street in San Francisco with my partner when I heard someone call out, “Are you Davy?” Lawrence had recognized me from inside his ceramics studio. I returned the next day to see his work — and they were absolutely stunning ceramic forms. We Come to This Place for Magic will be his debut exhibition, and I’m honoured that he’s trusted me, and travelled all the way to the UK, to present it at Queeriositie

Stigma (2025), by Lawrence Cuevas. Copyright held by the artist.

The fair began today with a ticketed preview from 6-9 pm, and will run through Sunday, September 28th. Today, Queeriosities held a ticketed preview for collectors, press, and cultural tastemakers, but the fair is open and free to all on Saturday and Sunday. Get tickets here.

Emma Cieslik

Emma Cieslik (she/her) is a queer, disabled and neurodivergent museum professional and writer based in Washington, DC. She is also a queer religious scholar interested in the intersections of religion, gender, sexuality, and material culture, especially focused on queer religious identity and accessible histories. Her previous writing has appeared in The Art Newspaper, ArtUK, Archer Magazine, Religion & Politics, The Revealer, Nursing Clio, Killing the Buddha, Museum Next, Religion Dispatches, and Teen Vogue

view all articles from this author