Whitehot Magazine

November 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

November 2025

Breakthrough: Patricia Watwood’s “The Fey Wild” at New York Artists Equity Association Inc.

Patricia Watwood, Blow Pop, 2023, oil on linen, 24” x 13”

Patricia Watwood, Blow Pop, 2023, oil on linen, 24” x 13”

By DANIEL MAIDMAN November 28, 2025

I have been following Patricia Watwood’s art for about 20 years at this point. In 2005, I was finding my footing as a figurative artist oriented toward classical rendering, in a culture actively hostile to my kind of artwork. I spotted Watwood’s early paintings in the other art magazines – you know, the ones that aren’t ARTnews, Artforum, and Art in America.

Watwood was practicing my kind of art, and seeing what she was doing felt like seeing Toto tugging Oz’s curtain aside. Her work, and its reception, showed up the universality of the postmodern art scene for a manufactured consensus. Other doctrines, other traditions, were alive and well. She was proof.

I like to follow artists over time. You can see their thinking and inspirations evolve, and you gain a more textured and contextualized appreciation of their work. There are no active artists I’ve followed longer than Watwood. Her body of work forms a prominent strand in the visual tapestry of my entire life.

I have witnessed her master her craft, and I’ve witnessed the restlessness that comes with mastery. I’ve watched her forays into different ideas, ideologies, and image-making paradigms. I’ve been able to see the contributions her most extreme experiments gave to her core set of images and tools.

Any sufficiently skilled artist is able to make work that combines their established strengths on the one hand, and on the other – controlled stabs at tackling and incorporating new ideas. For a long time now, Watwood has been working toward a new approach to color.

There are two basic forms of visual cognition, marked by different brain structures: form-perception and color-perception. I happen to be a form-perceiver. Watwood is a color perceiver. To me, her relationship with color is one of the most interesting facets of her work. She began with something I have never been able to do: perceptual color painting. That is, she sets her colors on her palette, looks at her subject, and then paints the colors she sees. Certainly she applies color theory, and a scaffold of selected colors in her work. But she also just looks at a thing, sees what color it is, mixes that color, and puts it on the canvas.

To me, who sees shape and form, this direct expression of color is an ineffable mystery of art. And yet when I mentioned Watwood mastering her craft, that was a large part of the craft I meant. She perfected her skill at painting vivid, living color.

A sad thing about mastery is that its pursuit is more rewarding than its possession. Once you’ve got it, the energy and vitality of the struggle deflate, and you need to find a new struggle – hopefully once which builds upon the mastery you worked so hard to acquire.

This is what Watwood did with color. Having perfected her skill at observing real color and transmuting it into a shimmering, heightened equivalent on canvas, she sought more. Usually it wasn’t explicit, but in the form of “controlled stabs” set within an image which already worked on the basis of her established strengths.

It appeared to me that what she wanted to do was establish a vocabulary of pure color, of a sensational experience of color which overrode the specifics of the scene. This is not a new idea. What made it new was that it was hers, that it interacted with her sense of composition, of figure and meaning. And also her strange, personal palette: hot pink, Hollywood night blue, burnt yellow, acid green…

She had the skill and she had the goal. But she couldn’t quite make the leap. There was something arbitrary to her attempts, and the arbitrariness leant them a quality of the half-hearted. Even as she continued to produce gorgeous drawings and paintings drawing on the universe of images and techniques she had struggled so hard to acquire, there was another set of work, the color experiments, which were full of faith and frustration, but never quite realized their ambitions.

This is why I would call her new solo exhibition “The Fey Wild” a breakthrough. Because she did it. She made the leap, and she got to that magical land on the other side of the river. Standing on its banks, she turned back to us, the viewers, extended her hand, and said “Come with me – this is the way.” The way – the bridge from here to there – is the body of work in her show.

Patricia Watwood, The Captured Faun, 2023, oil on linen, 40” x 30”

Patricia Watwood, The Captured Faun, 2023, oil on linen, 40” x 30”

During the period of exploration leading up to the work in “The Fey Wild,” Watwood was painting her not-quite-there experimental color pieces. But she was also going to rural Pennsylvania every year with artist friends to spend a week painting nude models in the landscape. It was not immediately obvious that these paintings would provide her the key to what she sought. They were staunchly representational and strove toward color fidelity. But looking back over years of this work, it is clear now that the practice was exactly what she needed: a relaxed space with supportive artist friends – a task which lulled the censorious part of the artist’s mind: “yes, these are skilled paintings of the figure and landscape” – and a sequence of incremental dares to herself to stylize the color, to compose around pure blocks of color, to just see what would happen; after all, these were lower-stakes paintings and she had space to allow herself to fail.

A selection of these paintings are presented in a back room of “The Fey Wild,” and I believe they provide the roadmap she took to her current radical relationship with color.

Patricia Watwood, Emerald Wild, 2023, oil on Stonehenge Paper, 22” x 30”

Patricia Watwood, Emerald Wild, 2023, oil on Stonehenge Paper, 22” x 30”

But even with her breakthrough in color achieved, she still had to get from the playful studies to fully realized artworks, to artworks that did matter if they failed. The component she still needed, at that point, was not the color. It was what she wanted to color with it. Her roots are in the image, and she could only complete her journey when she found the right images for her project.

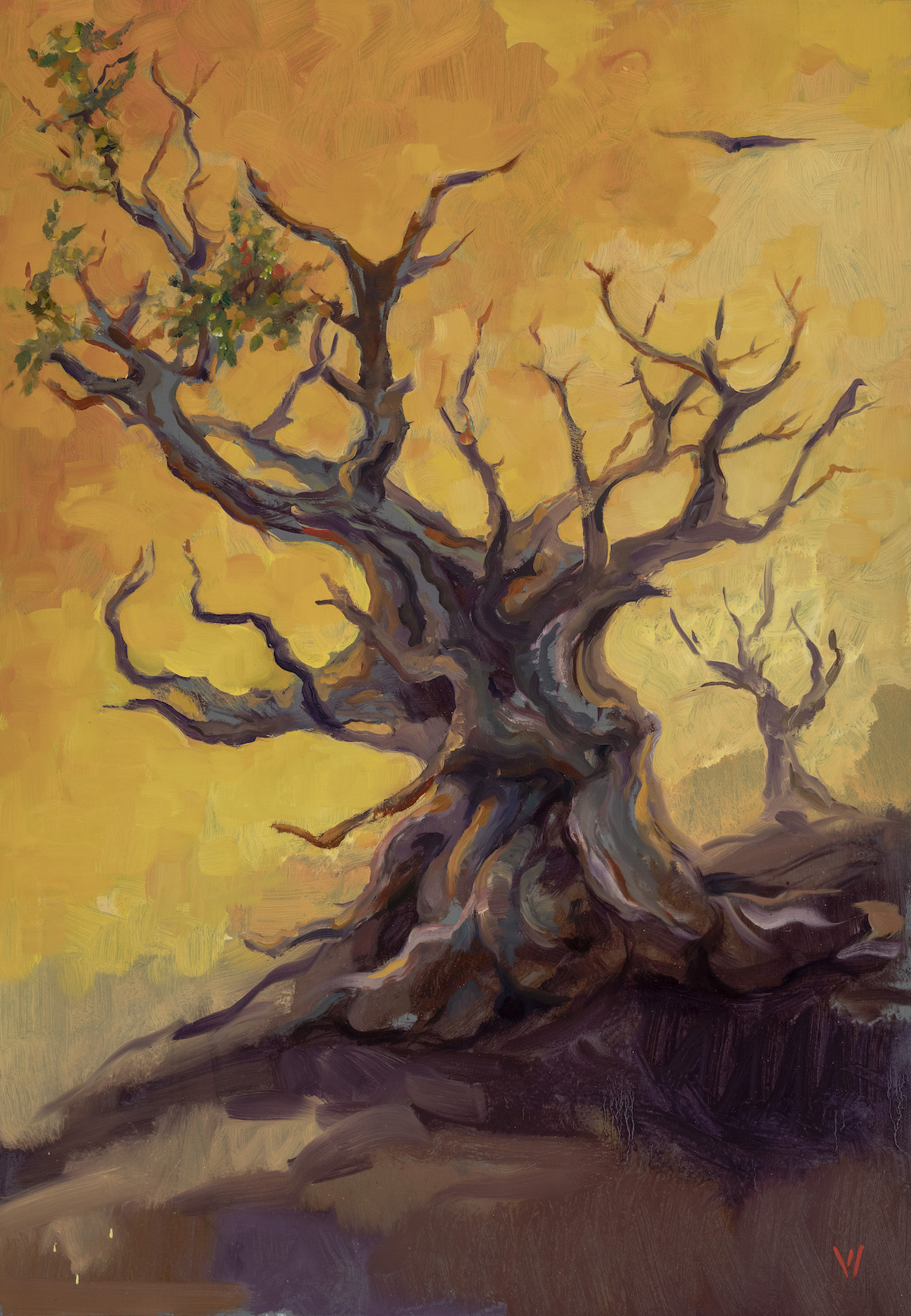

Patricia Watwood, The Prometheus Tree, 2025, oil on paper, 20” x 14”

Patricia Watwood, The Prometheus Tree, 2025, oil on paper, 20” x 14”

In the end, she found them. She has performed a strange synthesis of two bodies of thought she has been considering for years. On the one hand, with her background in theater and theater design, she has a longstanding familiarity and fascination with A Midsummer Night’s Dream. And on the other hand, as a mother of two gender-nonconforming young adults, she has had ample opportunity to consider queer identity; being a painter, she naturally saw it in visual terms first.

In her mind, the two worlds, Shakespeare’s charmed nightscape and a certain corner of the queer and trans scenes, fused into a single magical world, Watwood’s world, the Fey Wild with which she has titled her show.

Patricia Watwood, Peasblossom and Mustardseed, 2025, oil on linen, 22” x 26”

Patricia Watwood, Peasblossom and Mustardseed, 2025, oil on linen, 22” x 26”

Traversing this interior landscape, she generated image after image, roaring with color, color combined in ways it has never been combined before, color flooding narrative scenes, color spilling past the canvas so that the show had to become part installation art, festooned with spray-painted fabrics and massive paper flowers.

So many of us are trapped inside a chrysalis, imprisoned by walls built to protect us as we transformed, walls which have long outlived their function. In our cramped cell we intuit the outside world. We complete our growth but, remaining trapped, grow old and die without ever emerging. So many artists go through this. I’m not sure if you’ve ever had the experience of seeing an artist emerge from their chrysalis, coming awake, coming fully alive.

They emerge with mature powers, but these powers bend the knee to a primeval childhood impulse to make a picture. It is an impulse which remains frustratingly mute for the many years it takes to develop the skill to express it. During this time it may flicker out.

Not for Watwood. Having stepped out of her chrysalis, childhood’s vision is restored to her, but transformed and broadened by adulthood. She sees the world with fresh eyes and paints it with great powers. She is full of color and life.

I’m not sure if you’ve ever had the experience of seeing that, but I hope you get to, at some point in your life. It is one of the landmarks in the long story of human potential. Meanwhile, even though you may not know Watwood yourself, you can get a sense of what she’s accomplished from her show – if you find yourself in lower Manhattan before December 6, do go by the gallery space of New York Artists Equity Association and enjoy the torrent of love and vitality and invention and color in “The Fey Wild.”

Patricia Watwood, Titania and Bottom, 2025, oil on linen, 48” x 56”

Patricia Watwood, Titania and Bottom, 2025, oil on linen, 48” x 56”

--

Patricia Watwood

The Fey Wild

until December 6, 2025

New York Artists Equity Association Inc.

www.nyartistsequity.org

245 Broome Street

New York, NY 10002

Tel: +1 (931) 410-0020

Gallery Hours: Wednesday to Saturday, 12 PM - 6 PM

Daniel Maidman

Daniel Maidman is best known for his vivid depiction of the figure. Maidman’s drawings and paintings are included in the permanent collections of the Library of Congress, the New Britain Museum of American Art, the Wausau Museum of Contemporary Art, the Long Beach Museum of Art, the Bozeman Art Museum, and the Marietta Cobb Museum of Art. His work is included in numerous private collections, including those of Brooke Shields, China Miéville, and Jerry Saltz. His art and writing on art have been featured in The Huffington Post, Poets/Artists, ARTnews, Forbes, W, and many others. He has been shown in solo shows in New York City and in group shows across the United States and Europe. In 2021 it will be included in the first digital archive of art stored on the surface of the Moon. His books, Daniel Maidman: Nudes and Theseus: Vincent Desiderio on Art, are available from Griffith Moon Publishing. He works in Brooklyn, New York.

Follow Whitehot on Instagram

view all articles from this author