Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

The End of Naturalia at the 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale – Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology - Portugal

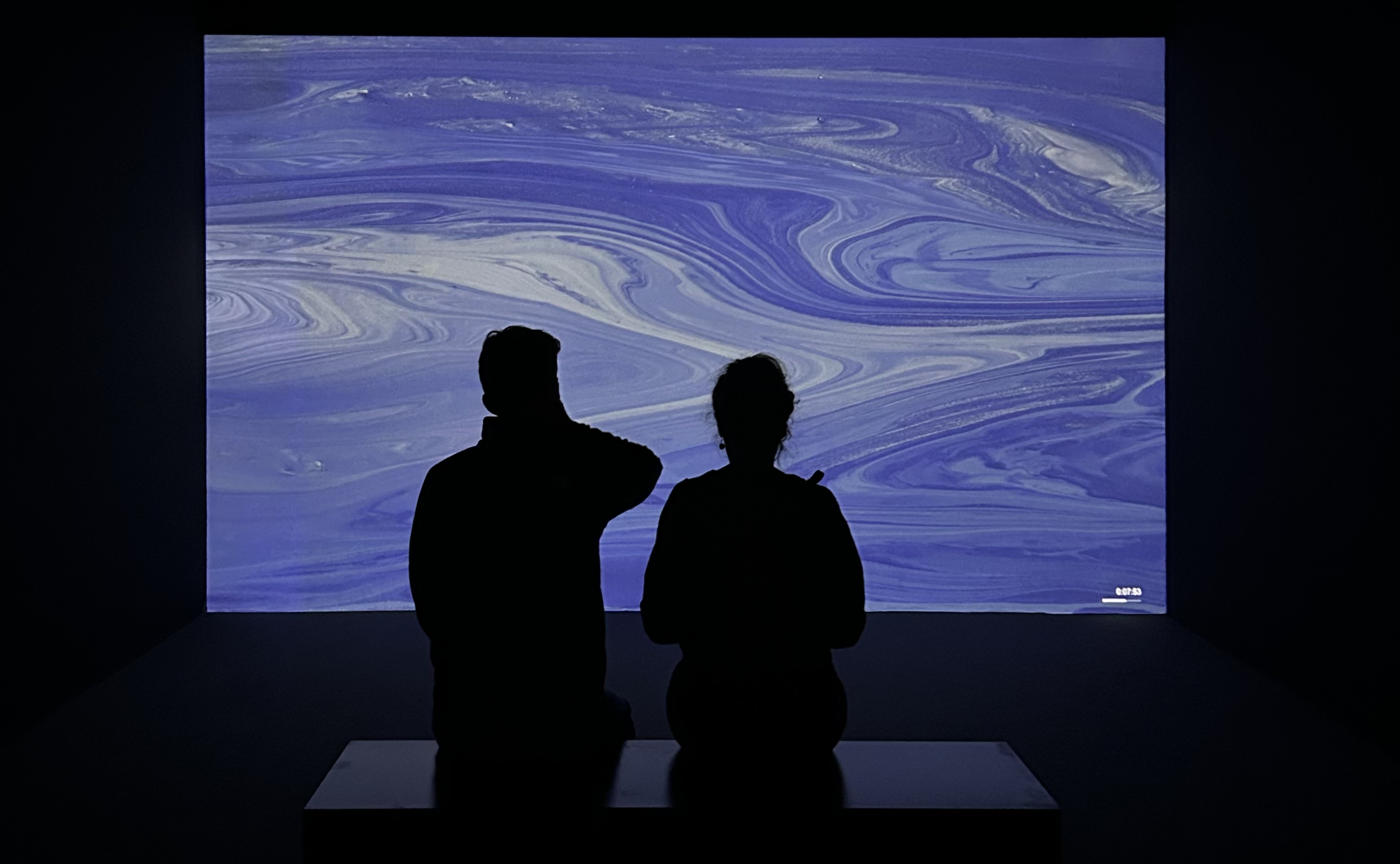

Fluxes, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, Lisbon, 2025. Photo: Matilde Fieschi.

By Flávio Rocha de Deus January 16th, 2026

Between October 2025 and January 2026, the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) in Lisbon hosted Fluxes, one of the three exhibitions comprising the 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale. Curated by Ann-Sofi Rönnskog and John Palmesino (Territorial Agency), this year the entire triennale was organized around the guiding question How Heavy Is a City? This question does not seek, in its intention, a definitive answer. Rather, it operates as a ground for understanding and critique. In doing so, the triennale inverts a consolidated logic of urban thinking, in which weight is commonly conceived as a category applied to commodities, infrastructures, and waste circulating through the city, but rarely to the city itself as a material totality.

The exhibition suggests that, in the context of the Anthropocene, the urban must be understood as a planetary concentration of matter, technical decisions, and extractive chains whose effects extend far beyond their physical boundaries. The strength of Fluxes lies precisely in transforming this theoretical diagnosis into a sensorial, spatial, visual, and bodily experience within MAAT.

Petroleum by Iwan Baan, 7 Trienal de Arquitectura de Lisboa, Museu de Arte, Arquitetura e Tecnologia, 2025. Foto: Flávio Rocha de Deus.

In Petroleum, Iwan Baan shifts the observer’s attention to the vast bitumen extraction operations in Alberta, Canada, territories usually perceived merely as “resources to be exploited” rather than places with their own material and political histories. The photographic series functions almost as a vertical archaeology of the technosphere: the seemingly homogeneous ground becomes an archive of layers inscribed with machines, drainage systems, craters, and industries. Placed within the context of Fluxes, the work suggests that the weight of the contemporary city is not limited to its visible buildings but begins in the very process of making the subterranean accessible and transformable into global infrastructure, a gesture that forces us to reconsider the idea of the city as something delimited by buildings and streets, and instead see it as a chain of material and ecological effects extending across continents.

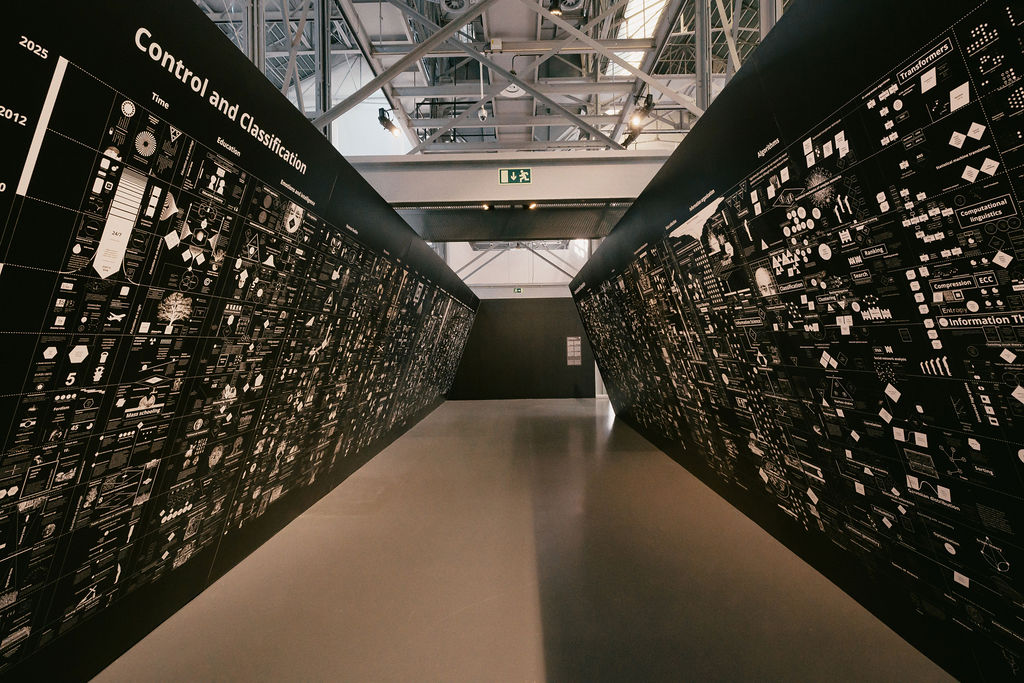

In parallel, in Calculating Empires, Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler demonstrate that the “weight” of the city is not only material but also epistemological and political. Through an extensive historical cartography, the work reveals how techniques of measurement, calculation, and classification have always been intertwined with forms of domination, whether colonial, military, or economic. It is neither a celebration nor a demonization of technology, but a visual exposition of its grammar of power within the flow of human history.

Calculating Empires by Kate Crawford and Vladan Joler, 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, 2025. Photo: El-Hey

Perhaps the great merit of Fluxes is that it leads visitors to shift the conceptual inquiry of human weight beyond its most immediate image: the physical mass of buildings. Through photographs of extraction sites, data visualizations, investigations into dust, and energy cartographies, the exhibition constructs an expanded image of the city as a technosphere, a field in which matter, information, and politics are inseparably entangled. Works dealing with microscopic particles remind us that the Anthropocene also operates at nearly invisible scales, infiltrating homes, archives, and bodies; meanwhile, pieces based on atmospheric data and energy networks make perceptible what usually remains abstract: the continuous movement of carbon, heat, and capital. Thus, Fluxes does not present isolated cases but a shared regime of problematization: the city appears as a planetary process that is simultaneously physical, cognitive, and ethical.

In Museographia (1727), Kaspar Friedrich Jencquel, one of the pioneers of what would become museology, classified museums and their exhibitions according to the nature of objects: cabinets of naturalia and cabinets of artificialia. The former designated collections of objects originating in nature, untouched by human action (skeletons, minerals, plants). The latter exhibited objects essentially fabricated by humans, such as technical instruments and artworks. This distinction was not merely classificatory; it expressed a worldview in which Nature and its phenomena were seen as independent and disconnected from human life, both individual and collective. Culture and Nature were, in essence, distinct domains.

What the Anthropocene, an era defined by irreversible human impact on the planet, makes evident, and what Fluxes addresses with clarity, is the collapse of this separation. It is no longer possible to observe nature as something external to human action. Atmosphere, oceans, soil, climate, and biodiversity all bear deep marks of technical, economic, and political intervention. In this context, even what we might still call naturalia can no longer be conceived outside artificialia. Today, nature is permeated by human systems at every level.

It is from this conceptual collapse that the exhibition struck me both sensorially and intellectually. At first glance, Fluxes appears to be an exhibition of artificialia, which is, after all, what architecture fundamentally is. Yet what is at stake throughout the exhibition are the natural processes that architecture, across its various dimensions, infers, measures, manages, or controls. The city thus emerges as the privileged site of this ontological confusion. It is the ultimate product of the artificialization of the world and, simultaneously, the medium through which nature returns as a problem. The city becomes, therefore, both the laboratory and the symptom of the Anthropocene.

Fluxes, 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, 2025. Photo: El-Hey.

Fluxes, 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, 2025. Photo: El-Hey.

Another point worth noting is the exhibition design of Fluxes, which I believe was notably virtuous. The use of space and its dimensions was highly effective. Vertical curtains of transparent plastic, suspended from the industrial ceiling, created a landscape that immediately evoked an avenue: a micro-city. The choice of thin, translucent polyethylene produced an ambiguous effect. There was visual lightness, fluidity, and permeability due to its transparency and texture; yet, at the same time, this imperfect transparency also revealed the accumulation of multiple overlapping layers. Scale played a decisive role. Visitors felt small before these “plastic skyscrapers,” while understanding the data they evoked required looking down toward their bases, which hovered in midair.

Fluxes, 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, 2025. Photo: Flávio Rocha de Deus.

Fluxes, 7th Lisbon Architecture Triennale, Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology, 2025. Photo: Flávio Rocha de Deus.

The installation avoided any classical monumentality, yet produced a diffuse monumental presence. There was no linear route or clear hierarchy among the works. The exhibition operated through superimposition, much like the urban systems it analyzed. Visitors did not leave with answers but with the weight of implication. The plurality of approaches in Fluxes transformed the curatorial question into an open investigative field, in which diverse registers interrogated the deep structures of urban life.

Flávio Rocha de Deus

Flávio Rocha de Deus is a Brazilian philosopher, professor, and art critic. He holds a Master’s degree in Contemporary Philosophy and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art at the Federal University of Ouro Preto (Brazil). Member of the Brazilian Association of Art Critics, he is also the author of the acronym fradde.art; writes essays and art criticism for national and international platforms and publications.

view all articles from this author