Whitehot Magazine

November 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

November 2025

Exhibition Review: “David Szauder: Glitches & Glory” at Elza Kayal Gallery, Tribeca (October 29 - November 21, 2025)

Projected still from one of Szauder's moving image works. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

Projected still from one of Szauder's moving image works. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

By LIAM OTERO November 25, 2025

As a writer of Contemporary Art, it was bound to happen sooner or later that I would write a piece dealing exclusively with AI and its relationship to art. Most people who know me are aware of my opposition to that endlessly slavish stream of AI-generated imagery that has been overwhelming the Internet given its soulless production and digital theft of all sorts of image data along with the deleterious effects it leaves on the environment because of its energy consumption.

Having said all of that, this review will take a markedly different tone. The best way I can describe it is that the artist in question - David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976) - is an example of an artist who is approaching AI as a tool that can be domesticated in such a way as to retain creative authorial individualism without running afoul of digital and creative ethics. In short, as one visitor at the exhibition’s opening remarked: “It’s an optimistic idea of AI done right.”

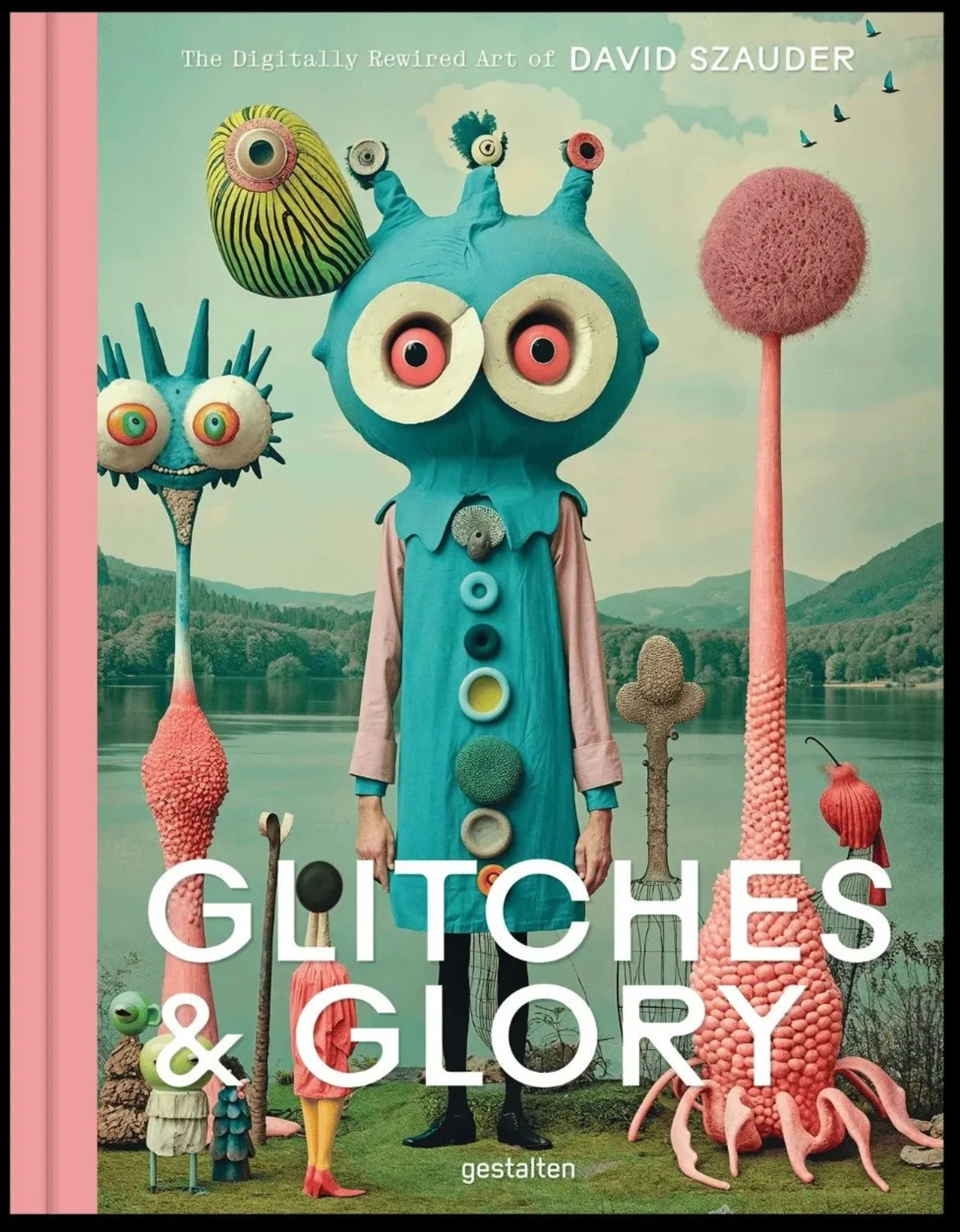

Glitches & Glory: The Digitally Rewired Art of David Szauder (2025). Published by gestalten.

Glitches & Glory: The Digitally Rewired Art of David Szauder (2025). Published by gestalten.

Having received a copy of his book Glitches & Glory, I can affirm I’ve seen his work here and there on Instagram for the last few years - the artist has over 1 million followers, so it was inevitable his imagery would enter my visual scope. Szauder’s art is Surreal, but not that of André Breton’s early-20th Century school of thought ubiquitous with painting or sculpture. Instead, Szauder’s art is more aesthetically complimentary to the cinematic surrealism of filmmakers Alejandro Jodorowsky, Suzann Pitt, or Jean Cocteau for its endearing weirdness - people with slices of bread for heads, Steam Punk-esque contemporary revisitations of Dutch Baroque portraiture, or unsettling, occultish-looking dance ensembles.

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Food Memories 2, 2025, digital print. 12 x 18 inches. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Food Memories 2, 2025, digital print. 12 x 18 inches. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

I don’t want to get carried away with the visual analyses as I think Szauder’s work is really fascinating to observe, but it’s time to discuss precisely why his approach to AI actually stays true to genuine artistic expression. Szauder possesses a comprehensive knowledge of Art History and Computer Science from his impressive educational and professional backgrounds that include earning a degree in Intermedia Art at the Hungarian University of the Arts in Budapest and teaching courses on art, AI, and technology at Moholy-Nagy University of Art and Design. His CV is much too long to summarize, so I will leave you with a link to check it out, but essentially, this is someone who is an authority on the intersections of creativity and technology.

Photo of a few of the archival materials that informs Szauder's art. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

Photo of a few of the archival materials that informs Szauder's art. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

Armed with that understanding of how computers operate as communication tools, Szauder managed to devise his own coding system and programming software to generate images based on a particular prompt or archival image materials he feeds into its design. Alongside the image stills and projections of Szauder’s work, the source archival content he utilizes were exhibited, which include: 1980s Hungarian newspaper & magazine clippings; pattern sheets from the German fashion magazine Burda; old manuals; a poem by the Hungarian modernist poet Dezső Kosztolányi (1885 - 1936) typed by Szauder's grandfather on an aging, yellow paper, etc.

What this means is that there is none of the digital theft all too common with standard AI-generated content that pulls from trillions of data streams, for this feels like a more high-tech production of collaging ephemera. Yes, his content is generated, but it’s not slavish or random as we would associate with generic AI art. Szauder, like any great painter or sculptor or photographer, has a cohesive style and look to his work that was carefully choreographed according to the specifications inputted forth by the artist himself. The human touch, the hand of the artist, is preserved fully intact.

A selection of Szauder's digital imagery as hung in the gallery. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

A selection of Szauder's digital imagery as hung in the gallery. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

Szauder may be an intermedia artist who goes about his work as a dual fine artist and computer scientist, but he seems to wear a couple other hats: director and storyteller. This intensive focus on refinement and effective execution can be easily correlated with a pre-AI artist, the British-born Harold Cohen whose AARON painting machines were the subject of a huge exhibition at The Whitney Museum last year and were featured in Gazelli Art House’s booth at this year’s Armory Show. Until Cohen’s death in 2016, he remained stringently devoted to his life’s work in recognizing the capacity to harness technology as a tool for creative expression, rather than as an end in itself. I believe Szauder can be likened in this way.

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Still Life, 2024, digital print (edition of 150). Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Still Life, 2024, digital print (edition of 150). Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

Having spoken with Szauder and read an interview he gave with Hype&Hyper in 2023, it comes across quite clearly that Szauder recognizes AI as a neutral tool and that it is only how you use it that can dictate its ethical parameters; perhaps the same can be said of a paintbrush - a paintbrush can be used for authentic creativity or it can be used to plagiarize (albeit with more manual labor involved) or employed to express hateful and offensive ideas.

Szauder’s exhibition was a real eye-opener as it makes a respectful case for AI’s capacity to serve as a potentially viable artistic medium and I appreciate that Elza Kayal Gallery was brave enough to stage this kind of exhibition given the polarizing discourse surrounding artificial intelligence and creativity. As I read back on my earlier paragraphs here, I know I still have a hesitancy to even fully accept AI as a true art form, but Szauder’s AI - as an individualized, self-contained system like Harold Cohen’s - is a separate entity with which I am comfortable to enjoy and recognize as art. WM

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Me, Myself, and AI, digital print (edition of 150), 18 x 12 inches / 46 x 30 centimeters. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.

David Szauder (Hungarian, b. 1976), Me, Myself, and AI, digital print (edition of 150), 18 x 12 inches / 46 x 30 centimeters. Image courtesy of Elza Kayal Gallery.