Whitehot Magazine

September 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

September 2025

The Empathic Portrait: Sonia Stark’s Charcoal Drawings

Sonia Stark, Untitled A6, 2011, 8.5 x 11 in.

Sonia Stark, Untitled A6, 2011, 8.5 x 11 in.

By DONALD KUSPIT, October 2020

Man can no more survive psychologically in a psychological milieu that does not respond empathically to him, than he can survive physically in an atmosphere that contains no oxygen. Lack of emotional responsiveness…the pretense of being an inhuman computer-like machine which gathers data…do no more supply the psychological milieu…for the delineation of a person’s psychological make-up…than do an oxygen-free atmosphere…supply the physical milieu for the most accurate measurement of his physiological responses.

-- Heinz Kohut, The Restoration of the Self (1)

Delusions Of Grandeur: Posing For Posterity (Some Art Historical Context)

Looking at some of the more famous portraits of the Renaissance, we notice an air of detachment, aloofness, even a certain “scientific” coldness toward the person portrayed, that is, a certain lack of empathy for him or her, a certain blindness to his or her inner life, feelings, however they might be suggested, as Mona Lisa’s smile suggests that she has a certain emotion, somewhat limited, as the fixed smile suggests, that is, a smile that has been reified, treated as a thing-in-itself, separate from the rest of her self, an isolated facial phenomenon, a sort of curiosity worth precisely—“scientifically”—analyzing, just like the many other facial expressions Leonardo studied and analytically described, as his notebooks show. Leonardo had no empathy for the Mona Lisa, that is, he was unable, or rarely able to “experience the inner life of another,” but took “the stance of an objective observer”(2) to his human subject matter, for him implicitly not much different from the machines he designed. Leonardo’s use of sfumato suggests an empathic response to his subject, for it creates what seems like an emotional atmosphere around her, but it in fact has nothing to do with emotion—to give it “expressive” purpose is to misunderstand its meaning, that is, the science it signifies, for it is “a painting technique for softening the transition between colors, mimicking an area beyond what the human eye is focusing on.” In other words, it serves a perceptual purpose rather than expressive purpose. It exists not to create an emotional atmosphere but to describe a perceptual experience, a way of articulating an “out-of-focus plane,” an area “without lines or borders, in the manner of smoke or beyond the focus plane,” which is the way Leonardo described it.

We deceive ourselves when we read an emotional meaning into it, regard it as adding emotional atmosphere to the scene, rather than simply as a technical device for representing invisible, immaterial space—making invisible space visible, materializing immaterial space, so that it has pictorial presence. Leonardo knew that nature abhors a vacuum which is why he filled the vacuum of pictorial space with smoke. It is also a bit of a smoke screen, a pseudo-atmospheric drop cloth on a stage set, for the Mona Lisa—the model—is posed, an actress in a sort of theatrical tableau, all the props in place—the landscape, the gown—for the performance of the painting, for Leonardo is an impresario, a master designer, his perfectionism evident in his mastery of detail. However imaginative, his technique—scientific, with nothing left to chance--is the key to the work, Mona Lisa’s smile being an epiphenomenon of his empiricism, more particularly what Baudelaire called “positivism,” the “positivist” artist “wanting to represent things as they are, or rather as they would be, supposing that I did not exist.”(3) The positivist universe is “the universe without man.” That raw universe is the spreading landscape behind the refined Mona Lisa, the landscape from which she seems to emerge like Aphrodite from the ocean, the cosmic landscape in which she is the beautiful earthly flower, standing out of it like a grand illusion epitomizing it, condensing its infinite extension into her finite presence. It is the landscape around Florence, as the image of the Arno River Valley in the distance behind her left shoulder indicates, suggesting that the Mona Lisa is an attribute of it, implicitly a personification of it, just as the ancient woodland nymphs personified elemental nature, the natural universe in no need of human beings, in which man is an intrusion, an anomaly—but not woman: is the Mona Lisa a symbol of Mother Nature?

Sonia Stark, Untitled S10, 2016, 18 x 18 in.

Sonia Stark, Untitled S10, 2016, 18 x 18 in.

Leonardo had no empathy for Cecilia Gallerani, the Lady with an Ermine, ca. 1483-1490, or Lisa Gherardini, the Mona Lisa, ca. 1503-1506. He was simply commissioned to paint their portraits as best he could. Mona Lisa’s smile is not “enigmatic,” as has been said. It was simply empirically precise, and he worked hard to make it accurate. He supposedly “continued working on the painting as late as 1517,” suggesting he was unsatisfied with it—didn’t think he had gotten it right, that is, didn’t think he had described her appearance with scientific precision. Leonardo was a detached observer of nature, including human nature, more precisely of appearances, whether of natural objects or human objects, for he treated everything objectively, treated ostensibly extraordinary human beings—such as the apostles in The Last Supper, 1495-1498--as ordinary if odd objects, of interest for their external appearance rather than their inner life, for their external appearance subsumed their personal feelings. The consistent empiricist and insistent perfectionist, Leonardo regarded each of his works as a scientific experiment which had to be carried out carefully and correctly, however long it took. He labored long and hard on The Last Supper, “troubled over his ability to adequately depict the faces of Christ and the traitor Judas.” A perfectionist to the bitter end, Vasari noted that on his deathbed Leonardo lamented that “he had offended against God and men by failing to practice his art as he should have done.”

Leonardo was a cognitive artist and objectivist, emotionally detached from his subject matter, observing and describing it as meticulously as possible, abiding by its appearance, be it a human being or a scenic landscape, trusted as the indisputable and indispensable truth about it. Leonardo was the epitome of the detached objective artist, an artist with little if any empathy for his human subject matter, indeed, seemed incapable of empathy, for empathy interfered with observation by emotionally attaching one to its human subject matter, precluding the detachment necessary to scientifically practice art. Seemingly incapable of projective identification, he was unable to internalize other human beings, which is perhaps why, in intellectual compensation, he devoted himself to analyzing their social façade, as if they were illusions in a Potemkin’s Village. More particularly, by reason of his radical objectivism or experimental realism, as the critic Walter Pater called it, Leonardo was incapable of seeing through let alone getting behind their social façade, all the more so because it seemed to be all that they were. Instead of conveying the inner life of Cecilia Gallerani or Lisa Gherardini or the apostles, with its stream of complex changing emotions, impossible to fix in a single expression, Leonardo emphasizes the one and only socially proper emotion--the pleasing social age-appropriate smile of the young ladies. For he has been commissioned to make a socially pleasing portrait, to portray the sitter in all her formal splendor—and vanity. He was hired to validate their high rank, not to fathom their feelings. As far as he was concerned they had no inner lives. They exist to be exhibited; their smile is socially defensive not emotionally revelatory.

Strange as it may seem to say so, Philip Pearlstein is Leonardo’s decadent heir, for his nudes are nothing but technical feats, formal constructions, their form of limited aesthetic consequence, their inexpressivity—feelinglessness--confirming their mechanical character. Many of them are accompanied by dolls, suggesting that they are more dead than alive—waxworks rather than living beings. There’s not a hint of expressivity about them—not a smile. Pearlstein’s female bodies are inanimate objects compared to Leonardo’s female faces, animated by their smiles, hinting at a subjectivity—their inner life--however incompletely and unwittingly, not to say unexpectedly, even by them. However obliquely and unconsciously, Leonardo is inadvertently acknowledging the so-called mystery of woman—but then her mysterious smile simply acknowledges the mystery of Leonardo’s art, the ingenious art with which he rendered it, indeed, invented it, for it lacks the fleeting quality of a smile, the transience that makes it so intriguing and inviting, that arouses curiosity. Fixed forever, it becomes a mask, even an ironic death mask, for death is static, the living face dynamic, the vitalizing smile timely, the artificed smile timeless.

Cecilia Gallerani was the lover of Prince Ludovico Sforza, the powerful Duke of Milan, who belonged to the prestigious Order of the Ermine, suggesting that the ermine she carried confirmed that she was his property and a princess. Lisa Gherardini was the wife of the wealthy Florentine silk merchant Francesco del Giocondo, leading one to wonder whether the real subject of her portrait is her expensive silk gown. Are their portraits advertisements for the rich and powerful men who paid for them, the men behind the scene, as it were? My point is that they were wealthy aristocrats—they were the socio-economically elite, the ruling upper class—and that their portraits set the precedent for such portraits as Anthony van Dyck’s portrait of Charles I in Three Positions, 1635-1636 and Diego Velazquez’s portrait of Philip IV in Brown and Silver, 1632 and Jacques-Louis David’s portrait of The Emperor Napoleon in his Study at the Tuileries, 1812, and of many other portraits of royalty, as well as many other socially prominent people, such as Sir Thomas More, portrayed by Hans Holbein the Younger in 1527, and Gilbert Stuart’s Lansdowne Portrait of George Washington, 1796, another wealthy, powerful ruler, an aristocrat in principle if not the name. Like Leonardo’s “classical” portraits, that is, portraits that “classicize,” and with that “class-ify,” the sitter is always fixed in place, as though petrified, giving it an air of self-righteous authority, as though its existence was fated—rather than a matter of biological chance. Certainly there is no air of existential risk to them—classicized figures do not seem subject to the vicissitudes of life, let alone chance. Their portraits announce their delusion of grandeur; fixing their smiles forever, Leonardo announces his delusion of grandeur, for like God he immortalizes whatever he touches, the power to immortalize being his creativity. But it is only the socially superior who are worthy of immortality; their power and wealth make them his chosen people. Leonardo’s portraits confirm their delusion of grandeur.

Sonia Stark, Untitled B11, 2005, charcoal, 31 x 15 in.

Sonia Stark, Untitled B11, 2005, charcoal, 31 x 15 in.

I am arguing that Leonardo’s formal portraits have become peculiarly formulaic in the portraits painted by later artists in servitude to the portrayed—commissioned, even ordered to paint them, rather than painting them of their own free will—and thus unlikely to make a more spontaneous, insightful portrait, such as Sonia Stark’s portraits of a staring white woman, B11, 2005 and a staring black woman, S10, 2015. The former is full face, the latter in profile, and however different their races and faces, they are both pensive, even introverted, unlike Leonardo’s ladies, their extroverted smiles suggesting they are more matter than mind, that there is little behind their pleasing smiles, driven by external necessity rather than inner necessity, to use Kandinsky’s distinction, that is, made for social reasons rather than personal reasons. Proudly depersonalized, they lack the personal presence and intimate appeal of Stark’s black and white models, more or less the same age as Leonardo’s ladies, but clearly lacking their social standing, and too free-spirited and independent to be interested in having it. Cecilia Gallerani and Lisa Gherardini are public figures rather than private individuals, and thus have no reason to be themselves—to be true to themselves would be to betray the powerful men on whom they are dependent, who supported them in the grand style to which they have clearly become accustomed. Their faces are certainly passive—indeed, inert--compared to the lively faces, with their complex expressions, of Stark’s models.

The left eye of the white woman is wide open, and looks beyond the spectator—there is no interest in meeting the eye of the spectator, let alone look appealing, play to the public, as Leonardo’s two grandiose sitters do. In ingenious contrast, her right eye is narrower and smaller than her left eye, and seems to look inward while the right eye stares into space—outward. The subtle contrast between them, along with the bolder contrast of the white face, with a thin, tenuous shadow stretching from the right side of the chin through the nose—interrupted by a patch of white that stretches from the left side of the face, flattening the cheek as it does so—to the dusky hair, underlines the different directions of, not to say contradiction between, the model’s gaze by magnifying it, amplifying it in space. Similarly, the torrent of black hair that crowns the head and covers the eyes of the black model abruptly contrasts with her white nose and white cheek, thinly covered by shadow—her chin has a heavier but still transparent cover of shadow, while her upper lip is thick shadow and her lower lip white but underlined by black shadow stretching to her neck—conveys a tension between unconscious feeling and conscious self-control. The unresolved dialectic between them, not to say their irreconcilability, is confirmed by the blatant difference between the black model’s white breasts and shadowy right arm, its outer and inner edges framed by linear black gestures, making them almost as emphatic—an emotional statement by a forceful person--as the black hair. Both the black model, with her head held high, and the white model, with her lowered head—she looks down rather than proudly straightforward and upright, as the black model does--have an emotional dignity, credibility, and humanity that Leonardo’s sitters lack, all the more so because their studied pose is altogether at odds with the unself-conscious poise of Stark’s models.

They are both completely relaxed, unlike Leonardo’s stiff ladies. Stark’s warm-blooded models don’t have to pretend to be other than they humanly are, unlike Leonardo’s ladies, who seem peculiarly cold-blooded. The mountains behind Lisa Gherardini suggest she is a phenomenon of nature, just as Cecilia Gallerani’s ermine suggests she is a phenomenon of nature. But Lisa Gherardini seems more than human, as the sublime mountains behind her suggest, and Cecilia Gallerani seems less than human, as the animal she holds in her hands suggests. The mountain and the animal are their respective attributes, self-symbols signaling their place in the scheme of nature, and status symbols signaling their special place in society: high place in the case of Lisa Gherardini, who was a wife, ambiguously high and low place in the case of Cecilia Gallerani, who was the low born mistress of a high born man. (An ermine lives on the ground, a mountain rises above it.) Stark’s models are simply their all too human selves, which is why they have no need of symbolic attributes to justify and complete their existence, status symbols to make them seem more meaningful than they would otherwise be. Stark’s fresh young women are free spirits compared to Leonardo’s self-important ladies. They’re about the same age, but it is their attitude to life as well as lot in life that is different—radically. The Renaissance ladies are finished beings with predetermined destinies—idolized by Leonardo’s portraits, inflexibly in place, they have no emotional reason for being, and as such seem incompletely human—or is it more than human, considering Leonardo’s glorification of them. (It has been suggested that their permanently fixed smiles are implicitly that of the ever-loving virginal Mother of God [God being Leonardo?], or as Freud argued, the idealized mother of Leonardo, who was an illegitimate child.) In sharp contrast, Stark’s all too human models are in process of becoming--in perpetual emotional motion, conveyed by the perpetual motion of Stark’s hand. They are emotionally alive rather than mummified by art.

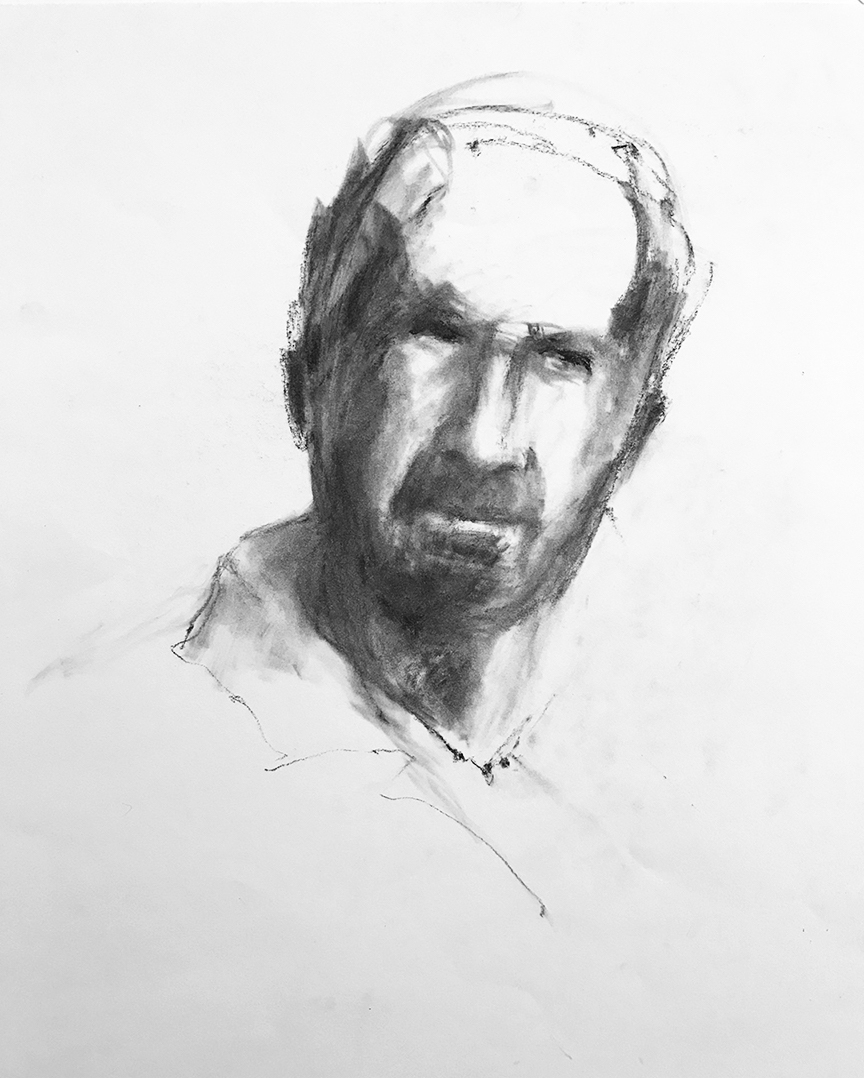

Sonia Stark, Nolan, 2020, charcoal, 15 x 20 in.

Sonia Stark, Nolan, 2020, charcoal, 15 x 20 in.

The difference between Stark’s black and white symbolizes the contradiction between the unconscious and the conscious. But they are as connected—inseparable—as the white drawing paper and black charcoal Stark uses to sketch the faces of her models. They are the material medium that makes them manifest. Stark holds a small piece of charcoal with two fingers, treating it as a kind of third finger, and with that an animated part of her hand. When she draws—places and moves the charcoal on the drawing paper—her hand becomes the most animated part of her body. The swiftness or slowness with which she draws is indicative of its rhythmic power. More broadly, the energy she uses to draw draws on its energy, confirming its aliveness—she truly “draws from life.” This is why there is always a sense of immediacy in a hand-drawn image. In contrast, the brush with which one paints is placed in a handle, which is what is held when one paints. The handle the painter holds is a kind of prosthetic device, certainly an intermediary between his fingers and his canvas, which is why a painting always seems mediated rather than immediate, which is the way a drawing is experienced. The seeming immediacy of so-called painterly painting—heavily impasto not to say densely layered or thickly packed paint--is an illusion created by the fact that the paint literally rises above and completely obscures the flat canvas, even seems to volcanically explode from it, so that it seems not to exist, or exist more in name than substance. There seems to be nothing behind—nothing supporting--paint often aggressively—violently--thrown in your face, as in Pollock’s painterly paintings, emblematic of the oceanic unconscious, as he said, in which he drowned. In a charcoal drawing the paper is always conspicuously present, integrated with and as fundamental as the charcoal, each adding to the other’s presence, the inseparability of artist and model implicit in Stark’s drawings.

Drawing is directly connected to what Freud called the body-ego, which is “ultimately derived from bodily sensations,” adding that it is “the projection of a surface,” first and foremost “the skin.” The skin of Leonardo’s females and Stark’s females is smooth and soft, but parts of the skin of Stark’s females is hardened—textured--by shadow, suggesting they have been marked (marred?) by life—haunted by experience. They have suffered—and survived their suffering, the shadows on them announce it--which is why they seem to jump out of their portraits rather than remain hermetically sealed in them, like Leonardo’s females, strangely otherworldly and detached however worldly their dresses. Stark draws the skin of her models—drawing seems to get into and even under the skin of the drawing paper. It is thinner than canvas and unprimed or “prepared,” usually with gesso, as canvas is, so that the paint never makes contact with it, bonding with it, as charcoal seems to bond with drawing paper, but layers it, refining it, which is one of the reasons that painting seems more detached than drawing, and drawing seems more raw than painting. A drawing subliminally draws one to its subject matter, unconsciously attaching one to it, while a painting adds an aura of detachment to it, however “striking”—“excited”--the painting. Charcoal drawn skin is always more poignant than painted skin.

I am suggesting that Stark’s plain-speaking materials are one of the reasons her drawings are not essentializing portraits like the richly painted portraits of Leonardo (and those of the many other painters working in the so-called “grand manner”) but rather existential likenesses. The grand manner portrait serves pretentious human beings by elevating them into artistic heaven, deceptively dehumanizing them in the process, for to become immortal is to become divine, and with that timeless. They have an otherworldly presence however nominally worldly. Leonardo’s self-important ladies are not in our space, but in a hermetic space of their own. In sharp contrast, Stark’s more straightforward portraits of unpretentious human beings presents them in all their being-thereness and time-boundedness, to allude to Martin Heidegger’s theory of Being in the World and Temporality. They are clearly of this—the spectator’s—world. They are in open space, as we are, move with ease in it, as we do. Just as they are processing emotions, so time is processing them. They are not finished products, like Leonardo’s grand ladies, but unfinished lives.

Stark’s models have an air of autonomy and independence about them. They are not posing for Stark, but simply present. She must take them as they are rather than impose conditions on them—make them stand or sit in a certain way, hold themselves this way or that way. Just as she makes no demands on them—they just have to be there for a certain amount of time—so they have no expectations from her. (Cecilia Gallerani and Lisa Gherardini expect Leonardo to make them look beautiful—idealize them.) Concentrated in themselves the models don’t need the spectator’s attention to confirm their existence—they don’t need to be admired to know who they are--as the subjects of the aristocratic portraits do. As naked and as fresh as the day they were born, Stark’s working models are unashamedly themselves, in contrast to Leonardo’s privileged sitters, their peculiarly defensive smiles perhaps apologizing for the power and wealth of their lords and masters. After all, the ladies are showpieces that distract from—hide—what is behind the scenes of their lives. Is it absurd to suggest that Ludovico Sforza and Francisco del Giocondo—ruthless men of the world--paid good money to have the otherworldly portraits of their ladies painted as a way of whitewashing their sins? Art has a way of making excuses for life.

Stark’s models are made of mortal clay not immortalizing myth, and as such suited to charcoal, a “mortal” substance—“an amorphous form of carbon, obtained as a residue when wood, bone, or other organic matter is heated in the absence of air.” “Dark or black,” in contrast to paint, a “colored substance spread over a surface to leave a thin decorative or protective coating” on it, charcoal informs the surface rather than lies on it—becomes ingrained in the surface--and as such has a deeper and more intense emotional impact than paint. Whether thickly or thinly applied to a surface, paint stays on it rather than informs it, and thus has a more superficial effect than charcoal. Colors convey conscious feelings, black plunges us into unconscious feelings. Color symbolizes feeling in every society, but in different societies the same color can symbolize different feelings. Thus in China people wear “otherworldly” white clothes at funerals, white symbolizing purity and brightness—perhaps enlightenment, that is, seeing the light, and transcendence, that is, ascending to heaven—and black clothes in mundane everyday life—in this here-and-now world. Death and life are sharply separated in principle. In contrast, in the United States and Europe people wear black clothes at funerals, black symbolizing death, loss, depression. Stark is an American artist, and black charcoal signifies death—all the more so because charcoal is a dead, inorganic material—the corpse, as it were, of living, organic material—but the white of the paper signifies life, even eternal life, as its luminosity suggests. Life and death are inseparable for Stark; funereal black and life-giving white interweave, an existential truth Stark’s ingenious use of charcoal and white paper acknowledges.

Certainly Stark’s use of charcoal is more incisive, insistent, spontaneous—free-wheeling (dare one say liberated?)--than Leonardo’s calculated, labored, “polished”—oddly mechanical--use of paint. (His constant scientificizing of art indicates that he is always looking for a consistent formula for inconsistent facts—and art.) Charcoal is organic, paint is inorganic, which is one of the reasons why Stark’s figures look organic rather than peculiarly inorganic, like Leonardo’s figures, as noted. I am arguing that charcoal is more telling of the emotional truth than paint; Stark’s charcoal gestures are more emotionally compelling than Leonardo’s meticulous surface. Paint is an artificial material, charcoal a natural material, which is why paint is more suited to making portraits that falsify life, as Leonardo’s portraits of the Florentine grand dames do, rather than portraits that tell the emotional truth about it. Stark’s portraits convey the True Selves of her models, Leonardo’s portraits show his sitters as socially compliant False Selves, to use the psychoanalyst Donald Winnicott’s distinction.(5) Every portrait made for posterity falsifies the portrayed by showing her in a false position. Every portrait made for the living moment tells the emotional truth about the portrayed because it conveys the artist’s lived experience of the portrayed—deep emotional engagement with her emotions, and thus their harmonious mix-up, to use the psychoanalyst Michael Balint’s concept.(6) In short, Stark’s portraits are empathetic portraits, Leonardo’s portraits are unempathetic portraits. They are not attuned to the inner life of their sitters, at best superficially suggested by their engaging smiles. Stark’s are attuned to the inner life of her models, which is why they seem to have no social life. They don’t smile for the spectator, they look inward.

As noted, the blackness of charcoal implies death, which is why it is a triumph to use it to convey life, not to say aesthetically paradoxical. Stark’s matter-of-fact females are uninterested in drawing attention to themselves—both are completely self-absorbed, as though unaware of Stark, the artist drawing their portraits—unlike Leonardo’s females, who look Leonardo in the eye, aware of him and no one else, he existing to mirror them as perfectly as he can—and anonymous, their namelessness allowing them to freely be their natural selves, to feel what they feel rather than to abandon their natural and spontaneous feelings to perform their social roles, maintain their social position. Stark’s seemingly quick study of their features catches the quickness of their feelings, no doubt because their subjects did not have to inhibit their feelings to main their dignified pose, the pose of dignity imposed on them to confirm their superiority to the rest of humankind. Stark’s ordinary anonymous familiar figures have more depth and complexity than Leonardo’s extraordinary unfamiliar named figures—we dare not approach and talk to them, while Stark makes us feel that we can approach and talk to her models. They are emotionally multi-dimensional, as the shifting tones of black they embody suggest, while Leonardo’s females have only one emotion, as their singular smile indicates.

Stark’s “romantic” figures—figures whose faces are charged with feeling, reminding us that romanticism is about feeling, as Baudelaire famously said, and that form is an expression of feeling, every line used to compose or “configure” the face giving form to the feeling of the person portrayed—are altogether at odds and incompatible with Leonardo’s “classic” figures. This is not only because they are of different classes, but because the latter can never truly be themselves in public—let themselves go, let their emotions flow. In contrast, the former have no status to lose by being their emotional selves, by showing their feelings—in all their changing variety--in public. Stark’s models can let themselves go, as it were, unself-consciously be themselves, show what they feel on their faces, while Leonardo’s self-conscious sitters lose face if they do, which is why they their faces are fixed in place, as though any change in expression would betray themselves. They have no inner life, only outer form. Strange as it may seem to say so, their smile is self-censoring, for it hides more than it reveals. Romanticism is about time and change, which is what we see in the faces of Stark’s models, not the timeless and unchangeable, which is what we see in the faces of Leonardo’s sitters.

The difference between then is the difference between a commoner, a young woman we can meet on the street, and a member of the nobility, a young woman who never goes out on the street alone, let alone unguarded. Indeed, she is always on guard, her smile a shield and guardian, an apotropaic device warding off evil, including the evil that may lurk within her, for she is not exactly pure. Leonardo’s regal ladies are like hothouse plants that never see the light of day; they would wilt if they are exposed to sunlight. Stark’s everyday women blossom with inner life, their feelings flourishing like wild flowers. We can approach them, get close to them; we can never approach Leonardo’s grand dames. The distance between us and them is unbridgeable; they are untouchable, and do not touch us—move us—as Stark’s women do.

Stark’s faces are made of mortal clay, not immortalizing myth, which is what the faces of Cecilia Gallerani and Lisa Gherardini are made of. It is why we can identify with Stark’s sitters, come as emotionally close to them as she does, and why we keep our distance from Leonardo’s sitters, all the more so because they are all too perfect, and as such insufficiently human. They engage us with their smiles, but it has nothing to do with their hearts. Leonardo flatters them, Stark shows her ladies in all their realistic glory.

Just as Leonardo’s portraits became the model for the classical-type portrait idealizing socially superior people—a portrait meant to intimidate their social inferiors, to reduce them to worshipful subservience, to delude them into believing that the person in the portrait is immortal, that art literally immortalizes what it represents, magically confers immortality on mortal human beings--so Leonardo’s studies of the various expressions that seem to randomly appear on the face become systematized and hypostatized in Charles Le Brun’s scientific physiognomic formulas objectifying all the emotions in Méthode pour apprendre à dessiner les passions, 1698, neutralizing and de-personalizing them in the process. A Cartesian materialist, Le Brun systematically analyzed facial appearances with geometrical precision, anatomically dissecting them as though they were corpses of consciousness, detached from the feelings they communicate—for every feeling is a communication to someone--reminding me of the supposedly apocryphal story of Descartes kicking a dog and declaring, with scientific detachment not to say indifference, that its scream showed the workings of the gears in its body. Le Brun’s studious work, with its methodical description of feelings, each a peculiarly abstract construction, classicizes the emotions in the course of classifying them, and with that essentializes them, depriving them of existential meaning. They are all surface appearance with no depth—no more than proof of consciousness with no unconscious import—with nothing uncanny about them, nothing imaginative in their appearance on a face, nothing crying for recognition in their manifestation, left in the lurch when it is not met with another feeling, left to fade away when it is not responsively—and responsibly--mirrored, for it is meant to be appreciated and acknowledged not simply seen and recorded.

Deconstructing The Empathic Wall

The ultimate aim of all libidinal striving is thus the preservation or restoration of the original harmony…This unio mystica, the re-establishment of the harmonious interpenetrating mix-up, between the individual and the most important parts of his environment, his love objects, is the desire of all humanity. To achieve it, an indifferent or possibly hostile object must be changed into a cooperative partner, by what I have called, the work of conquest. This induces the object, now turned into a partner, to tolerate being taken for granted for a brief period, that is, to have only identical interests.

-- Michael Balint, The Basic Fault (4)

According to Balint, apart from “orgasm,” it is during “the sublime moments of artistic creation” that this “ultimate aim of all libidinal striving” is realized, adding that it “requires considerable skills and talents” to do so. For the “very brief moments” when this occurs—when “the individual may truly and really experience that every disharmony has been dispelled”—"he and his whole world are united in undisturbed understanding.” More particularly, when the disharmony between the portraitist and the portrayed is overcome, when the distance between them is bridged, when the social wall or difference that divides them is breached, when there are no emotional barriers between them, then the portrait is imaginatively convincing not simply mechanically precise. Then it seems to be fraught with feelings rather than merely matter of fact, becomes a “living likeness” rather than simply correct---then we have what psychoanalysts call a “transference” to it, as though in looking at the portrait we are relating to someone we once knew, someone now a distant memory but still emotionally near, someone as resonant with feeling as we are, someone who exists in us despite ourselves. Then verisimilitude becomes vitality and the portrait becomes “all too human,” the person portrayed is convincingly individual and familiar, not simply another passing face in the crowd.

Jean-Antoine Houdon’s two portrait busts of the smiling Voltaire, both 1778—he wears a formal wig in one, which does nothing to change his informal smile—are sublime examples of such instantly emotionally engaging portraiture, and so is Vincent Van Gogh’s Portrait of Doctor Gachet, 1890, in all his melancholy pensiveness. Both capture the emotional essence—the inner being---of the person portrayed, confirming that he is a unique individual. One of a kind human being, he paradoxically conveys a universal emotion, consummately embodying it in his face. Like them, I will argue that Sonia Stark’s portraits again and again achieve a “harmonious interpenetrating mix-up” or “harmonious partnership” with her sitter, be it a man or woman. They show her remarkable capacity for empathy—it is inseparable from her creativity, indeed, to have an empathic relationship to a person is to have a creative relationship with them, for it gives them the psychological atmosphere in which they can breathe and feel alive, to allude to Kohut’s remark. She seems to be at her empathic best when she is engrossed in making a portrait: Stark’s spontaneous emotional responsiveness to her sitters, her instant engagement with them, the seriousness with which she takes their existence, the respect she has for their personalities, her admiration of their individuality, brings out the human best in them. One might say that her artistic concern for them–it is more than curiosity, more than the routine interest--celebrates their individuality—pays homage to their existential uniqueness. Keeping them alive by portraying them, which is a way of mothering them, brings out and confirms their aliveness, which is what a caring art and artist can do for a model who trusts the artist, and expects nothing from them except appreciation of her existence.

However distinctive Voltaire and Dr. Gachet may be, however accurately Houdon and Van Gogh have captured their appearance, they use their faces the same way Leonardo used the faces of Cecilia Gallerani and Lisa Gherardini: as a platform for a universalized—and with that peculiarly depersonalized and standardized—presentation of a familiar facial expression conveying a commonplace feeling, a feeling of happiness, contentment, and self-containment in the case of Leonardo and Houdon, a feeling of sadness, not to say depression, in the case of Van Gogh, Dr. Gachet leaning his head on his hand in the traditional pose of melancholy, going back at least to Dürer’s Melancolia I, 1514. In sharp contrast, the faces of Stark’s sitters show a complex range of shifting emotions in a single glance, making her faces much more existentially resonant and her figures much more complex personalities than those of Leonardo, Houdon, Van Gogh, not to say all the regal figures in all the “professional” portraits of privileged, not to say self-privileging and self-congratulatory figures in the traditional portraits of the upper classes, portraits that function to underscore their nobility by implying that it is their divine right by way of the divine artist.

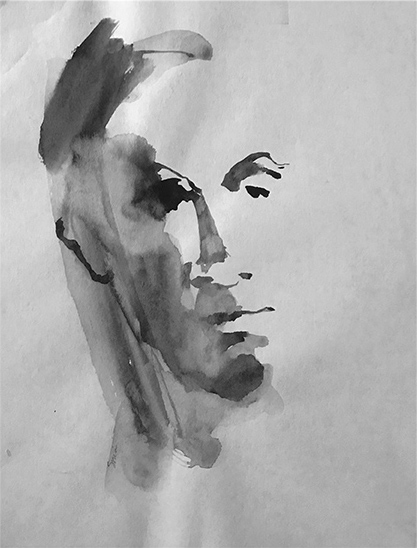

Sonia Stark, Dror, 2020, charcoal, 18 x 14 in.

Sonia Stark, Dror, 2020, charcoal, 18 x 14 in.

Rembrandt’s self-portraits assert his independence from his upper class patrons, but he places himself on the same social plane as they are, all the more so when he shows himself dressed up like some grandee, according himself the prominence they have by reason of their social power and business success. The narcissism of the works suggests that he feels superior to them—isn’t an artist always superior to his patron? Courbet shows plain people at A Burial At Ornans, 1848-1850, but none of them seems to have an inner life, implying that he had no empathy for them. He’s simply recording a scene—he’s a realist or positivist, to recall Baudelaire’s term. The figures are matter-of-factly given. They’re lined up like puppets in a pantomime, or an audience watching a play, or performers in a theatrical tableau. Courbet has no empathy for them. He’s simply recording their matter-of-fact appearances. Their faces are peculiarly blank; neither solemn not melancholy, as would suit the unhappy occasion, but feelingless. They’re simply putting in an appearance at the event; they have no presence—in contrast, say, to Courbet in his self-congratulatory self-portrait in Bonjour, Monsieur Courbet, 1854. Courbet usually stays on the surface; no “romantic” depth—no soft feelings for him, only hard facts. The poor people in Daumier’s The Third Class Carriage, 1862-1864 have no smiles to spare, but their sad faces are as fixed as the smiling faces of Leonardo’s ladies.

Delacroix’s Orphan Girl at the Cemetery, 1823 and portrait of Frédéric Chopin, 1838 are regarded as seminal romantic portraits—portraits in which feeling is all, in which the face is beside itself with feeling, seems to dramatize uncontrollable emotion—but the emotion is inflexibly in place (and controlled) on the face of the Orphan Girl, as though she was incapable of experiencing any other emotion, if a little more moving (and uncontrolled) in Chopin’s face, suggesting that he is experiencing the emotion, not simply having it—that it is an essential part of his being, not imposed on it, as seems to be the case of the Orphan Girl. “Delacroix was passionately in love with passion [feeling], but coldly determined to express passion [feeling] as clearly as possible,” Baudelaire, a fan of Delacroix, wrote. To express hot feeling as clearly as possible is to turn it cold—to reify intense feeling by representing it as though it is matter of fact, and with that routine. The face becomes a sign of feeling, rather than overcome by feeling: feeling sits on the faces of the Orphan Girl and Chopin passively, its momentum seemingly spent. It is as though Delacroix is congratulating himself for capturing the expression, but in doing so he has peculiarly misrepresented it, and with that the face, which always expresses more than one fleeting feeling in one quickly changing expression.

Feelings mingle rather than stand alone. They tend to be inseparable, one organically involved with—rather than mechanically leading to—another. Every feeling is inherently unstable; to stabilize it is to falsify it. There is really no one distinctive feeling, but a matrix of feelings. Delacroix’s portraits do not convey that matrix, as abstract expressionistic paintings seem to do—the matrix of gestures, intermixed and implicated in each other, seems to convey it in all its intricacy—but their saving grace is that they convey the emotional ambivalence of their human subjects. Thus the Orphan Girl looks hopefully to heaven even as she is terrified by death, and Chopin gazes into empty space while full of himself, reminding us that opposite feelings connect, that that there is a dialectic of particular feelings, the different dialectics converging in a matrix of feelings, so that one feeling can evoke any other feeling. The sense that the Orphan Girl and Chopin have more feelings than they show in Delacroix’s portraits—an expectation aroused by Delacroix’s painterly, proto-expressionistic handling in the Chopin portrait--is what makes them unconsciously convincing. It is that same richness of gestural, expressionistic handling, generating a matrix of feelings—each feeling implicated in the other, the portrait becomes an inward likeness, even as it remains outwardly representational--that makes Stark’s portraits unconsciously convincing, and with that true to life not just appearances.

Feeling, then, does not exist in the specious present, as it does in Leonardo’s portraits; a past and a future are implicit in its presence. What is lost in giving feeling specious presence is the unself-consciousness and naturalness with which it is expressed—the unself-consciousness and naturalness of Stark’s models in contrast to the self-consciousness and artificiality of Leonardo’s sitters. The “touchiness” of Stark’s vivid faces contrasts sharply with the noli me tangere look of Leonardo’s passive faces, unmarked by experience and with that beside the point of life. Stark’s faces are all-too-humanly changing, implying that her models have a future; Leonardo’s faces are unchanging, inflexible to the point of inertia, implying that his sitters have no future. They are finished products, rather than in uncertain process. Stark’s expressive faces show that feeling can’t be mastered—certainly not completely, as the peculiar incompleteness of her portraits suggests, nailed down once and for all time. Nor can it be completely understood, as Delacroix—and Le Brun—seem to think. I suggest that the reification of feeling that we find in their paintings--and Leonardo’s--is an intellectual defense against it. The intellectualization of feeling falsifies it.

One has to wait until the 20th century to get truly “romantic” portraits—unintellectualized expressions of feeling-full faces—faces fraught with raw feeling, faces that are not at home in polite society, faces that are uncompromisingly in the spectator’s face, faces with no defenses and social graces, rather than graceful posing for an audience in expectation of social approval. Among such self-expressive—rather than socially proper--faces are those in Edvard Munch’s The Scream, 1893, Käthe Kollwitz’s Self-Portrait with Hand on the Forehead, 1910, and Ludwig Kirchner’s Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915. Noteworthily, they are all self-portraits, suggesting that the artists have turned away from society, even turned against it—against the bourgeois society that appears in Munch’s Evening on Karl Johan Street, 1892, the Germany of the first world war in the cases of Kollwitz and Kirchner. faces informed by the private inner self rather than faces of the public outer self, faces that have personality rather than that seem impersonal, faces that we are drawn to in self-recognition rather than faces that keep us at a distance because they seem aloof, that seem emotionally shallow however ostensibly “expressive.”

“Affective mutualization is easy, uncomplicated, and free-form in infancy, and subject to wide variation in adult life,” the psychoanalyst Donald Nathanson writes. “It seemed only reasonable, therefore, to suggest that free-floating affective resonance is the norm for early childhood, blocked at some point in normal development, and reestablished by those adults to whom it seems interesting or unavoidable. I suggested that this block to primitive empathy was learned, offered as its label the ‘empathic wall,’ and demonstrated that it was essential for the formation of an adult personality. An adult who walked through life always vulnerable to the affect broadcast into the local environment would be unable to maintain personal boundaries, just as an adult who admits no information from the affect broadcast by others is truly isolated. The empathic wall must be strong when necessary but possess doors and windows that can be opened when necessary and optimal.”(5)

“How might this empathic wall be constructed?” Nathanson asks. “It is axiomatic that every culture on the planet requires that children mute their display of affect by the time they are three years old; we teach this every time we ‘shush’ a child and every time we value verbal over affective communication. To socialize a child is to teach it how to modulate the display of innate affect; socialization demands that a child yields its ability to take over interpersonal space through the broadcast of each affect at the maximal end of its range. Shaming labels like ‘immaturity,’ ‘childish,’ and ‘infantile’ drive home this message about affective broadcast.” It seems clear that Munch, Kollwitz, and Kirchner—and Stark’s models—broadcast their affects ashamedly, strongly suggesting that no affect can be completely socialized, that is, entirely inhibited. It may show itself in an involuntary bodily movement, a suddenly changing facial expression. It will be acted out one way or another—by way of expressionistic art, figurative or abstract—by way of some gesture or mood or behavior—some sign, subtle or not. It will acquire physical presence by dramatizing itself whatever the social circumstance. And however socially alienating it is, or rather how much it expresses social alienation, at the least incomplete socialization. it may simply be disrespectful of its audience, whether deliberately or unwittingly—deliberately, it seems, in the case of Munch and Kirchner, perhaps less deliberately in the case of Kollwitz, deliberately in the case of De Kooning and Pollock, among other “violent” and “violating” abstract expressionists.

I suggest that Leonardo does not get behind the empathic wall of his female sitters, and that his scientifically precise and socially respectable—intellectualized and aristocratic--painting is a kind of empathic wall, and why his sitters seem like objects rather subjects, the little emotion they are broadcasting in their smiles hardly mutualizing, that is inviting empathy. I think Stark does get behind—break through—the empathic wall of her sitters, which is why they seem like subjects rather than objects, why they seem to have multi-dimensional feelings rather than a one-dimensional feeling, why their faces broadcast feelings in all directions not only in her direction (and often not there, for many of them face away from her). They are completely unlike Leonardo’s sitters, who broadcast their one feeling in his direction, suggesting that it is exclusive to them, and exists only in his imagination, which is why it seems so “fantastic.” No one else can smile like the Mona Lisa, or rather no one else but Leonardo can make her smile the way she does, and only in his painting, which is why her smile fascinates so many people, and why it seems peculiarly unreal, an aesthetic lie rather than true to life, let alone emotionally authentic. I suggest that it broadcasts Leonardo’s feeling—not for her, but for painting.

I think this has something to do with the fact that Stark’s expressive gestures are like perpetually moving dance steps—one might say she dances her drawings, and why her faces never stop moving (unlike Leonardo’s, which are completely stopped, and seem unable to ever move again)—and seem freely formed, that is, free-form and lyrical, rather than planned and epic, like Leonardo’s paintings. Stark’s faces seem to suddenly appear on the drawing paper, while Leonardo’s seem to have been in the picture before they were painted. This may have something to do with the fact that Stark studied Isadora Duncan improvised, “informal” dancing when she was young. Leonardo studied with Verrocchio, a master of formal painting, paintings that followed a formula, that were constructed rather than unstructured, as Stark’s drawings seem to be, however much she clearly understands the structure of the face. Leonardo’s portraits are too perfectly painted—they’re meticulously constructed and hermetically sealed--to have affective resonance, as Stark’s spontaneously created drawings do, their informality, and the informality of her models, inherently resonant with feeling.

Sonia Stark, Untitled D8, 2011, 8.5 x 11 in.

Sonia Stark, Untitled D8, 2011, 8.5 x 11 in.

More to the expressive point, and their importance as drawings, they deconstruct the socially constructed empathic wall. Their spontaneity is in effect a battering ram against it—breaks through it, slowly but surely breaking it down. I suggest that the white space in Stark’s drawings—particularly the white forehead in such large works as A3, 2005; D15, 2012; S2, 2013; D6, 2014, S4, 2014; D22, 2015; D24, D25, D26, all 2015 (Deaf Man); S9, 2016; D32, 2017; D14, 2019; D29, 2019; D20, 2019 (Dora); D12, 2020 (Mikki); D13, 2020 (Nolan); D18, 2020 (Mona); D19, 2020 (Immigrant); D31, 2020 (Dror) and perhaps most strikingly in the three small works A5, A6, D8, all 2011--signals that her faces have no empathic wall, no social mask. The white space is where the wall has disappeared, vanishing into oblivion. No longer completely walled off from the viewer, the faces of the models resonate affectively and widely, every nuance of gesture conveying a feeling, spreading through the entire space of the drawing as it dances and converges with other gestures, and finally into the face of its viewer. With no defensive smiles, like those that turn the faces of Leonardo’s sitters into empathic walls, Stark’s models broadcast their feelings uninhibitedly. Every one of Stark’s faces arouses an empathic response from the spectator, every one of her spontaneous gestures is an empathic response to the model’s face. One emotionally engages with the model by way of Stark’s expressive gestures as well as by way of the model’s expression. One becomes attached to Stark’s models; we remain as detached from Leonardo’s sitters as they are from us. The social wall around them, symbolized by their dresses, confirms their detachment, which is finally why they make no difference in our lives, in contrast to Stark’s models, who make an emotional difference. WM

Notes

(1)Heinz Kohut, The Restoration of the Self (New York: International Universities Press, 1977), 253

(2)Heinz Kohut, How Does Analysis Cure? (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1984), 175

(3)Charles Baudelaire, “The Salon of 1859,” The Mirror of Art, Critical Studies, ed. Jonathan Mayne (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1956), 242

(4)Michael Balint, The Basic Fault (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1992), 74-75

(5)Donald Nathanson, “The Empathic Wall and the Ecology of Affect,” The Psychoanalytic Study of the Child, 41 (1986), p. 176. Is this why Baudelaire celebrated children, who widely broadcast their feelings, each of which is experienced as new—thus Baudelaire’s “sensation of the new”—and his remark that “genius is nothing but childhood recovered” in adulthood?

Donald Kuspit

Donald Kuspit is one of America’s most distinguished art critics. In 1983 he received the prestigious Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinction in Art Criticism, given by the College Art Association. In 1993 he received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Davidson College, in 1996 from the San Francisco Art Institute, and in 2007 from the New York Academy of Art. In 1997 the National Association of the Schools of Art and Design presented him with a Citation for Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts. In 1998 he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2000 he delivered the Getty Lectures at the University of Southern California. In 2005 he was the Robertson Fellow at the University of Glasgow. In 2008 he received the Tenth Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. In 2013 he received the First Annual Award for Excellence in Art Criticism from the Gabarron Foundation. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Fulbright Commission, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim Foundation, and Asian Cultural Council, among other organizations.

view all articles from this author