Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

Pictures from a Pandemic: Brenda Zlamany

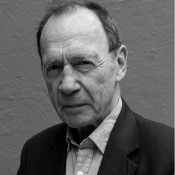

Portrait #85 (Anthony Haden-Guest), 2021. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

Portrait #85 (Anthony Haden-Guest), 2021. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

By ANTHONY HADEN-GUEST March, 2021

“Too many ideas don’t work,” Brenda Zlamany told me just before painting my portrait. “You need one or two good ideas in a watercolor.” She gave me a chair in her studio, organized four brushes and a pencil in her right hand, then turned towards me with a look that was neither warm nor cool, just unblinking, but her appraisal, made for closeness as if a light had just gone on.

We talked throughout, and not just a friendly chat, as you might have in a barbershop, but apropos. Sittings are the beginnings of a Zlamany portrait but not always the end, just as her portraits are not necessarily the end process of a single sitting, as with a photo shoot. She also cuts out images with which to experiment. “And then when I have figured it out, I make a life-size sketch. I like to get it right beforehand” she says. “I change the length of the legs, switch the head for a different body, maybe move the hair around. So it’s perfect ...”

Brenda Zlamany with "Self-Portrait Painting David Hockney Painting Oona", 2019. Oil on linen, 118 x 78 in.

Brenda Zlamany with "Self-Portrait Painting David Hockney Painting Oona", 2019. Oil on linen, 118 x 78 in.

It happened that one of Zlamany’s frequent sitters, Oona, her teenage daughter, had just sat for another painter with a magic gift for portraiture, David Hockney. “They didn’t want me to take photos in the studio while he was painting her.” she says. “I said she’s my daughter. So I took some photos. That night I had a dream that I was painting him painting her. I was a little upset that he was painting her. Because she’s my model and I don’t like to share my models.”

Our sitting zipped past so speedily that I was startled to learn it had lasted an hour and a half. The resulting image is attached. Brenda Zlamany was happy with it. Me too, very much so. What good idea/ideas had come to her, I wondered? No, it hadn’t been my commanding profile. “I liked the racy pattern of your jacket,” Brenda Zlamany said.” It worked with the heavy texture of your sweater, your white mask, pale eyes and skin “And I liked your hair. It looks like baby bird feathers.” - AHG

Brenda Zlamany writes:

During the pandemic, my studio practice has evolved. At the peak of the crisis in New York, I was terrified: my zip code in Williamsburg was said to be the epicenter, and ambulances kept us awake at night. My daughter was sent home from college, and while we sheltered, she became the focus of my paintings. But as the headlines went from Covid-19 to the killings of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, the fires on the West Coast, and other injustices, my feelings changed from terror to anger, a need to be heard.

I drew on two bodies of work begun before the pandemic. The first was a collection of sketches, photos, and recordings I had created in early 2019 during a month’s residency at the King Abdulaziz Camel Festival in Saudi Arabia. I was living and working then in a circus environment with thousands of performers from around the globe. The drama, alienation, joy, and melancholia of the circus made an apt metaphor for the plague time. I recombined my materials from Saudi Arabia to address feelings, search for truths, and create allegories. Free of distractions, my work days have been longer, so I made the circus project big, frantically starting new paintings before finishing previous ones to keep from obsessing. The scale kept me engaged, and rendering detail of drapery and patterns provided moments of beauty in a dark time.

Brenda Zlamany, Portrait #19 (Christy Rupp), 2000. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

Brenda Zlamany, Portrait #19 (Christy Rupp), 2000. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

Another practice in which I had been engaged before the pandemic was watercolor portraiture from direct observation. I began to miss the artist-subject interaction. Painting women in hijab in Saudi Arabia had familiarized me with the challenge of capturing a likeness with two-thirds of the face covered, so I started painting socially distanced portraits of mask wearers on my building’s loading platform.

After months of isolation, the people who sat for masked portraits were as hungry for a connection as I was. Sittings went on longer as we discussed our lives during the lockdown. Men, women, and children, from six to eighty-five, made statements with their masks. Some showed up with several masks and asked for fashion advice. We had conversations about what different patterns might signal. Some subjects would try to control the content of the portrait by wearing a mask, t-shirt, or hat printed with a political slogan. Some who had a plain mask worried that I would find it uninteresting to paint. I found that there is no such thing as a boring mask. When one scheduled sitter, Brian Hastings, arrived with a plain white mask, we decided to frame his face with his green hoodie. The combination of green and white with his skin and eyes made it one of the most dynamic images in the series. Liz Garvey’s plain mask allowed for a focus on her beautiful eyes and the tones in her hair.

Portrait #57 (Dyllon Young), 2000. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

Portrait #57 (Dyllon Young), 2000. Watercolor on paper, 12 x 9 in.

My watercolor portraits are always done from direct observation in a single sitting, unlike my oil paintings, which I make over months from a combination of sketches, photos, and live sittings. My oils benefit from painstaking discovery, a process of destruction and resurrection. But watercolor, an unforgiving medium, is best when one homes in quickly. When portraying Dyllon Young, I was drawn to the blue reflection on his forehead from his plastic visor, the shape of his hair peeking out above, and the dinosaur on his face covering. As I painted Daisy Crannock, the key moment was when her blue mask, seen through her yellow sunglasses, changed to blue-green.

As the masked-portrait project progressed, I discovered that I could achieve a likeness of some faces through the eyes, while with others the likeness depended on the nose or mouth. Although I cannot see the subjects’ masked features, their eyes change as their facial muscles move to create expressions. Sometimes I suggest a different expression to adjust the eyes. For instance, I might suggest that the sitter smile because the eyes have a sad shape. I also rely on the masks—their patterns or lack of patterns—to convey psychology or tell a story.

Many of my subjects are “repeat offenders,” artists who sat for portraits in my previous projects. These faces I know well, but indicating what I know and cannot see is a delicate balancing act. Subjects whose faces I have never seen present a different problem: if I meet them later unmasked, I am often disturbed that they look nothing like what I imagined while painting them. So I adjusted my protocol and now ask subjects for a peek at their entire faces before beginning.

So far I’ve completed eighty-five masked portraits. A break from the nose and mouth has been a welcome chance to master the eyes, and the masks have made me freer in my portraiture, permitting a pleasurable indulgence in pattern, design, and abstraction. This project celebrates our resilience, our individuality, our care for each other in a challenging time. I plan to continue these portraits for as long as we wear masks, but as the Covid rate changes and the news is dominated by other dramatic events, the focus of the project may shift once again. WM

Anthony Haden-Guest

Anthony Haden-Guest (born 2 February 1937) is a British writer, reporter, cartoonist, art critic, poet, and socialite who lives in New York City and London. He is a frequent contributor to major magazines and has had several books published including TRUE COLORS: The Real Life of the Art World and The Last Party, Studio 54, Disco and the Culture of the Night.

view all articles from this author