Whitehot Magazine

January 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

January 2026

February 2008, Nicholas Nixon @ Yossi Milo Gallery

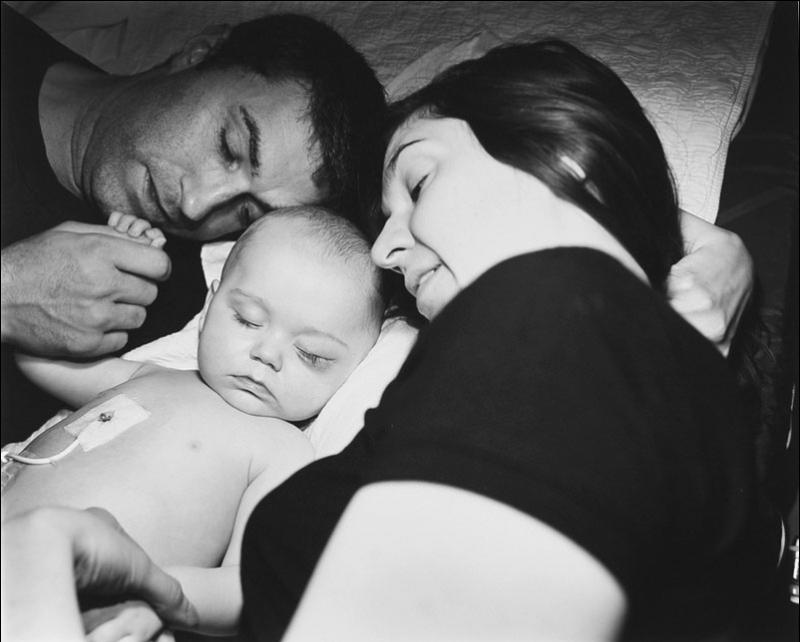

NICHOLAS NIXON: PATIENTS

At Yossi Milo Gallery, 525 West 25th Street

January 17, 2008 through February 16, 2008

Review by Hans Michaud

There is a sublime and profound intersection within the human being, that place where the mechanical flesh, the stuff that is bound by Newtonian physics, meets, nay, COLLIDES with the ethereal, the mind, the arguable non-locus of consciousness/intentionality. It is this location that is the most difficult to wrap both one’s intellect and one’s physical being around. It is also this location that proves to be the most humbling to all of us, an equal-opportunity leveler, in the sense that when we perceive ourselves or others in one light—the sexually-charged gaze of desire, for instance—we are jarred out of this reverie by a painful lucidity, a LURCH, when the person occupying our attention brings the reverie to a halt by, for instance, reciting multiplication tables. In other words, we are reminded that we occupy both positions/locations, not just one. In another instance, a group of people sit around a table and debate the finer points of any number of intellectual premises. These folks are willing themselves to become body-less brains. Suddenly, one of them suffers a heart attack. This snaps the group back into that accursed place, that intersection of MEAT and MIND.

Some physical sensations—say, raw pain—can burn down well-intentioned facades and notions of personality with decisive speed and efficiency. When we HURT it becomes clear indeed what the intentions are. Discomfort is a polite way of expressing what the suffering protagonist is subjectively feeling at the moment—agony is a better term—and the one clear desire is only to make the pain stop, no matter how, the sooner the better. But there is a difference between pain and lack of pain (“normalcy”?). It’s not necessarily easy to see the difference in others, but from a subjective standpoint it is certainly easy to feel the difference.

In this light, what of those of us who were born into a state of pain? What of pain being a constant referent, a stability, the touchstone on which one’s apprehending the world bounds from? Are they somehow inherently different than us? Do they know something that the rest of us don’t? What of someone who is born in a state that is radically different than yours and the only way to KNOW this is simply to look? Is there an understood difference from the perspective of the non-suffering who view the suffering?

Nicholas Nixon’s “Alexla Laci, Boston, 2007” is an image of a radically premature baby nestled in a caregiver’s arm. Alexla is small enough to almost—not quite—fit within the adult hand in her entirety. Her face looks elderly—no—it looks undone, bankrupt. She sleeps, her meager and imperiled frame the host to an oxygen tube, heart sensors and other mechanisms whose functions I’m entirely ignorant of—and her face, at least the way I’m projecting my own preconceived sense of being in the world and what a baby is SUPPOSED to look like when asleep—looks like what I imagine the personification of a devastated peasant society would look like.

Which is more harrowing and moving: images themselves of the suffering and the misshapen, or the notion that these maladies and misfortunes occur to that OTHER part of the human being—the one we love when it brings us pleasure but curse endlessly when it deals us pain—the body of course—and they are occurring to a part of us (possibly the entirety of us?) that is, for all intents and purposes, a machine, and a discreetly vulnerable one at that. How many of us have been greatly affected—trained medical personnel notwithstanding—by the sight of the dead or dying, the victim(s) of a car accident, casualties of war, whatever the tragedy may be? Why are we so affected? Of course we empathize, but that’s another matter and arguably entirely emotional and understandable from moral, psychological and evolutionary perspectives. What I’m getting at here is that INTERSECTION I mentioned earlier, that locus where the ether and philosophical come crashing into the MEAT. And the MEAT of the matter here is that this place—this discreet, razor-edged intersection—is where Nicholas Nixon seems to operate. For this reviewer, at least, Mr. Nixon sits comfortably among his subjects as entire and full human beings who occupy both places at once, and who, as a result of and despite whatever shortcomings they face at the time, embody deep and profound dignity.

When we view ourselves and each other as MEAT or, rather, as vulnerable machines, this is profoundly unsettling. I would argue that this is decidedly more unsettling than the notion of witnessing another in some form of physical suffering and feeling raw empathy. Not to discount empathy, of course, but this is one of the questions the work inspired in me. We can take these questions to their logical conclusion and reach the summation that every human being finds the possibility that he is MEAT and NOTHING ELSE far too unsettling for most.

The intimacy of the black-and-white photographs suggests that Mr. Nixon sat with the subjects, possibly got to know them. The photographs vary in lighting and somewhat in composition but all are resolutely stunning, the results of both the hand and eye of a master at the top of his game, an individual who has both the fortitude and the humbleness to be able to pull something like this off. I stood in Yossi Milo, slack-jawed for the better part of an hour, taking in some of the most jarring and sublime images I had the good fortune of witnessing in some time.

Hans Michaud

Hans Michaud is a freelance journalist in New York.

SEND THIS WRITER A MESSAGE:

| hansmichaud@gmail.com |