Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

June 2010, Mutek 2010: A/Visions. Interviews with: Alain Mongeau; Ben Frost; Carl Michael Von Hausswolff; James Kirby; Marsen Jules Trio

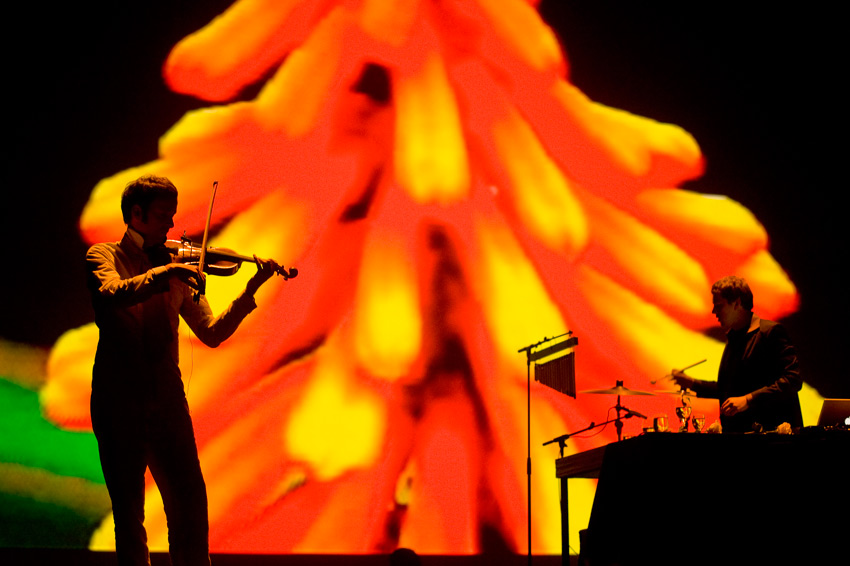

Carl Michael Von Hausswolff, Mutek 2010, A/Visions 4

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

Mutek 2010, A/Visions: Conversations on Sight and Sound

Mutek 11th Edition

Interviews with: Alain Mongeau, Festival Director; Ben Frost; Carl Michael Von Hausswolff; James Kirby; Marsen Jules Trio

Artists kindly selected for interviewing by Mutek Press Relations

All images courtesy Caroline Hayeur

Sound art is starting to fully enjoy its day in the critical sun. It’s inevitable, then, that the art world will more often seriously engage with those who have devoted their lives to making us listen - many of whom are themselves exploring work in which aural and visual intersect. Mutek, Montreal’s ‘international festival of digital creativity and electronic music’ gathers some of the most talented sonic minds from around the world; its A/Visions series offers a framework for exploring how they are working with vision. As discussions with Festival Director Alain Mongeau and four of the A/Visions artists support, it is an intensely interesting field but, as any, it can be problematic.

The A/Visions program has its roots in the fact that Mongeau originaly directed two festivals: Mutek was all about music and The Montreal International Festival of New Cinema and New Media was devoted to film and media culture. Post 9-11, funding for the film and new media festival was cut. “I had the problem of having one festival that was only covering part of the field, but it was so well positioned within sound and music it was kind of hard to bring it back to the middle. Through the A/Visions program we started re-introducing stuff that would work at the interface between sound and image.” However, he expressed some frustration about the current state of this interface. “If I look back I could say I am a bit disappointed in the evolution of artists working between sound and images, I think probably because it's a lot of work, and maybe because there's a lack of context to bring the work forward, but I sense, in the past two years, a lack of inspiration. There are cycles... People position themselves in relation to specific icons and it creates a blur, everybody's doing the same things, and then that pushes people to look into different directions. I'm kind of waiting to see what's going to come up next.”

Nurse with Wound, Mutek 2010, A/Visions 2

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

The 2010 A/Visions series comprised four multi-act showcases. Three were held in a traditional theatre where a gigantic screen was a backdrop to the performance space. In this context the visuals themselves generally seemed to be just that: a backdrop. Often seeming conceptually supplementary they nonetheless had huge presence due to the size of the screen and this created a tricky imbalance. For example, the film accompanying iconic Nurse With Wound was extremely well executed technically. But the subject matter, working class households who’s dead-eyed inhabitants remained soporifically oblivious to falling piles of entrails, encroaching flames, and total aquatic submersion was a heavy-handed representation of the dissonant sonic howls. In contrast, the final A/Visions showcase, A/V 4, was held in a smaller, open venue without seating and the visual elements consisted of sophisticated LED displays and basic spotlights. It was easily the most successful showcase of the four.

It’s worth asking why visual elements should be included in a sound tradition at all. The best answer is probably, ‘Because.’ More specifically, because it’s rich territory for creative exploration and expression. The worst has to be, ‘because the audience needs something to look at.’ We don’t. It would be like expecting Rothko to compose a few tunes to be piped into a gallery of his paintings. Music’s history has, however, has set a precedence. The architecture of performance, such as the theatre described above, orients a mass audience towards a specific focal point, and whether it’s a rock idol or the third violin we like to watch musicians play instruments. No matter how interesting technological sounds are, though, we are generally less enthousiastic about watching someone stand in front of a laptop. Mongeau made a very strong point: “One of the problems is that people are so used to seeing visuals with everything that if you don't provide them, it's like something is missing. We have to use that now to try and re-educate people to deal without the visuals.” It's somehow counterintuitive that this pure-acoustic approach seems much so better suited to an open space closer to that of a visual art gallery, than to the traditional stage-audience set-up of music performance.

Ben Frost; Mutek 2010, A/Visions 4

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

Visual elements can of course be valuable and successful regardless of whether a given piece is presented as 'music' or 'art'. But when images are implemented in such a way that they are conceptually subordinated to sound in terms of their perceived value, they do the sound a disservice by distracting attention away from it while adding very little. From Ben Frost’s perspective, “I think it's lazy art, this idea that somehow you need to compensate for a lack of a visual image by kind of projecting these kind of meta-narratives on your audience so that they 'get' what it is you're actually doing." Frost’s performance at A/4 4 was an expansive and often intensely desolate soundscape punctuated with blasts of white light and sudden explosions rough-edged noise. (It was, as Recumbant Media Lab’s Naut Human quipped, a soundscathe as much as soundscape.) The LED displays churned with diffuse static that did not flicker reactively to the sound. Instead, the static maintained a sense of density and refused to resolve, much like Frost's sonic environment. Though they were not complex, the visuals worked with the sound as opposed to against it.

Carl Michael Von Hausswolff, a composer and sound artist who has shown at Documenta, Manifesta and the Venice Biennale, also performed as part of A/V 4. He reflected, “I see many works where the video is some kind of substitute, just to be able to have something to look at, and I think that's ridiculous because I come from a much more structuralist point of view. In a poem, for example, every sentence, every word has to be important.” In terms of working audio-visually, Hausswolff has an intrinsically balanced approach: “For me it has never been really a problem, personally, with the visible arts and the audio arts. I mean from a conceptual point of view you can apply any kind of technique onto an idea.” Frost’s approach is equally, yet differently, integrated: “All of my schooling is in visual art. I was a painter first and foremost and that is how I still work. It's like being raised Catholic or something. I find myself constantly working on music, or at least researching projects, working towards a product, from a visual perspective.” On the other hand Marsen Jules, who collaborates with VJ Nicolai Konstatinovic, provided a succint counterpoint when asked if he ever created his own visuals. He looked at me for a few moments and then replied simply, “I am a musician.”

Marsen Jules, Mutek 2010, A/Visions 3

Visuals: Nicolai Konstantinovic

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

Using acoustic elements and laptops, the Marsen Jules Trio and Nicolai Konstatinovic presented a discretely segmented but tightly-integrated, collaborative approach to sound and vision. They also emphasised the fundamental difference between art that is exhibited as ‘finished’, and performed art that is based in experiment and experience, where certainty is sacrificed for the potential of sublimity. Improvisation is integral to the history of music and its performance, and it wil be interesting to see how this develops in audiovisual territory; in this A/Visions performance, though, the hovering, hypercoloured flora and languidly swooping gulls that dominated the screen did not offer much that was visually new or inventive. Speaking to all three trio members and the VJ at once, their responses were woven together like an exercise in conversational jamming:

Anwar Alam: We are sort of a quartet.

Konstatinovic: We are all individuals, but we have some moments on stage when the spirit is the same for a few moments, and this is something really wonderful. You can not plan it. If you try, it will not work.

Jan Phillip Alam: For one or two or three moments in the concert, we get this feeling that we work from the same place of inspiration. It's not possible to say it was perfect or that there were no mistakes, but we prefer to get such moments...

Jules: To astonish ourselves, also. Honestly, if you do it like that, there's two ways for it to happen: Everything gets out of control. The other side is, everything gets out of control - but it's completely beautiful.”

Frost described something similar: “With the performance of my work, for me it is a purely ecstatic feeling to connect with what's going on on stage. When it's right. Sometimes it's just downright awful and it doesn't work at all. But when it connects it's better than a fuck, it's really just the most... I'm not religious at all but there is a god element in there of connecting with something much larger than me."

James Kirby also spoke to unpredictability in performance: “I like happy accidents. You need this thing where it just works or it doesn't to make people think more. It's like tonight, the video I made is 42 minutes long and the show will roughly be 42 minutes. I have no idea if the audio is going to work with the visual and maybe at some point it does and maybe at some points it doesn't, I don't care, you know. I like to capture energy and I think if you overwork something, in the end you lose what you set out to do.” He took this approach to something of an extreme. Kirby was billed as The Caretaker, a project based in exploration of memory through historic recordings, but presented something quite different. The sound and video were both a densely layered and chaotically textured revisiting of 8 months spent binge-drinking in Berlin. The layering, mixing treatment was more successful with sound, and the distraction of this imbalance drew focus to the artist. He was calmly consuming a bottle of whiskey in the spotlight while operating his electronics and watching his film with what appeared to be genuine curiosity. Kirby himself became the most notable presence, especially in the last five minutes when he took off his jacket to reveal a sparkly shirt and launched into a rendition of Barbra Streisand's Memories, with extreme vocal distortion. Whether intentional or not he brought theatricality to both audio and visual elements and these were united more in the figure of performer than in the sound or video. This is perhaps not a surprising result for an artist who has a history of extreme performance (with his VM projects). Kirby also addressed the possibility that some sound is not be suited to any kind of viewing. “I've never really been comfortable doing Caretaker shows. Caretaker is this very delicate music and the thing is, the only way you could really do this and give it justice is to loop the records in front of people and process them live, but it's very difficult, I think, to make something that is very, very good and do this."

James Kirby, Mutek 2010, A/Visions 3

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

So what is the difference - or the similarity - between sound and vision in an exhibition or performance context? There are obviously no complete answers to questions like that, but it can generally be agreed that sound is experienced on a much more immediate and pervasive level. You can’t simply avert your eyes and make it go away. From Von Hausswolff’s experience, “You have to be in a very large installation in order to be inside an artwork from a visual arts point of view. But sound is very simple - you need a loudspeaker, and it's inside you. Automatically. And that's also why it can be problematic for a visual arts curator to curate exhibitions, groups shows, with sound art, because they really have to think in another way.” As an artist, he works extensively with single sonic frequencies, as well as with single light frequencies (aka, colours.) “The relationship between the frequencies and the colours are, for me, more from an emotional point of view,” he said, “I work a lot with low frequency sine waves, and I work with deep red photography and this - the colour and the frequency, they correspond for me. Red is red. It's a fantastic colour, it covers a range from hate to love and all that is in between. And the same thing with low frequency, it is very rich - low base tones are very rich in themselves.”

Von Hausswolff’s A/Visions performance pushed sound to sculptural, architectural, and physical limits. It actually hurt a little. There was a lot of ambient noise from the bar behind the exhibition area, and the first spatial experience was a gradual increase in volume that seemed to viscerally push the voices back with a mono-tonal wall of sound. Hausswolff’s explorations of frequency then pried open the space around you as the sound seemed to increase in both height and depth. At the same time, it spread inside, physically, with vibrations that were felt most sharply in the buzzing, soft tissues of the nose, but most intensely in the chest, around the organs, where the vibrational pressure was almost uncomfortable and definitively unnerving. It wasn’t quite painful but you were very aware of the potential for pain, possibly complete internal disintegration, should the intensity increase. The sonic experience was accompanied by red light that rendered the audience monochromatic in a similarly inescapable manner, and which, Hausswolff explained, was originally intended to be deployed with intensity closer to that of the sound. (Technical difficulties.) With reference to the architure of performance as described above, though, it's hard to imagine the experience being the same if I had been sitting in a theatre balcony as opposed to mere feet away from the speakers. And if it had been the same from that distance, I shudder to imagine the hypothetical experience of those in the front row.

Audience at Carl Michael Von Housswollf's Mutek 2010 A/Visions 4 performance

Photo: Caroline Hayeur

Whether overtly physical or subtly emotional, sound grabs you in a way that is fundamentally different from contemplating a purely visual work of art that stays quietly in its prescribed space, not entering yours unless invited by intentional direction of the eyes. Distance, either spatial or temporal, allows room for analysis - both personal and institutional. This is ultimately an integral part of the way art exists and grows in our cultural consciousness, but there is much to be said for the immediate and unmediated interaction with work that seems in many ways easier to establish with sound. Ben Frost: “I feel that's, if I may be so bold as to say, the problem with contemporary art: it's brain first, heart second... Don't get me wrong, I think about what I'm doing and there are ideas behind my work that I think are important, but ultimately those should come through the door after your initial, physical reaction. They're secondary problems... You go into any modern art gallery in the world these days and I would guarantee that 75% of the people will look at the writing on the wall before they look at what the writing is about. Which is just an insane notion. It's completely, completely wrong. And the idea that music is suffering those kinds of problems is very frustrating to me... 90% of the music you find these days you will find through reading a review on pitchfork before you actually hear it.”

Underpinning almost all of the current explorations is, of course, rapid technological advancement. It is the only reason many of the new ventures into sound and vision can even be attempted. Alain Mongeau: “Technology's always evolving, it opens up new fields, new territories...There's software that emulates the sound of instruments that can't actually exist physically, but exist mathematically in a virtual space. You can go further than the physical world. There are so many different avenues where you can explore territories that were not even conceivable before.” It’s little wonder that adapting these technologies to artistic expression is a formidable challenge.

Festivals like Mutek provide invaluable opportunities for international exploration and collaboration; they create community and a sense of continuity while pushing boundaries of learning and creativity. The trick is maintaining the space for experimentation, happy accidents and unpredictable ecstasies, while simultaneously maintaining a rigorous, integrated approach to the media and tools available. This is no small feat at time when the influences of tradition are intertwining like never before with the potential of technology. The dynamic can be intensely disorienting yet it remains exhilarating in its breadth of possibility.