Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

March 2011, Interview with Berlinde de Bruyckere

@font-face { font-family: "Arial"; }p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal { margin: 0cm 0cm 0.0001pt; font-size: 12pt; font-family: "Times New Roman"; }div.Section1 { page: Section1; }

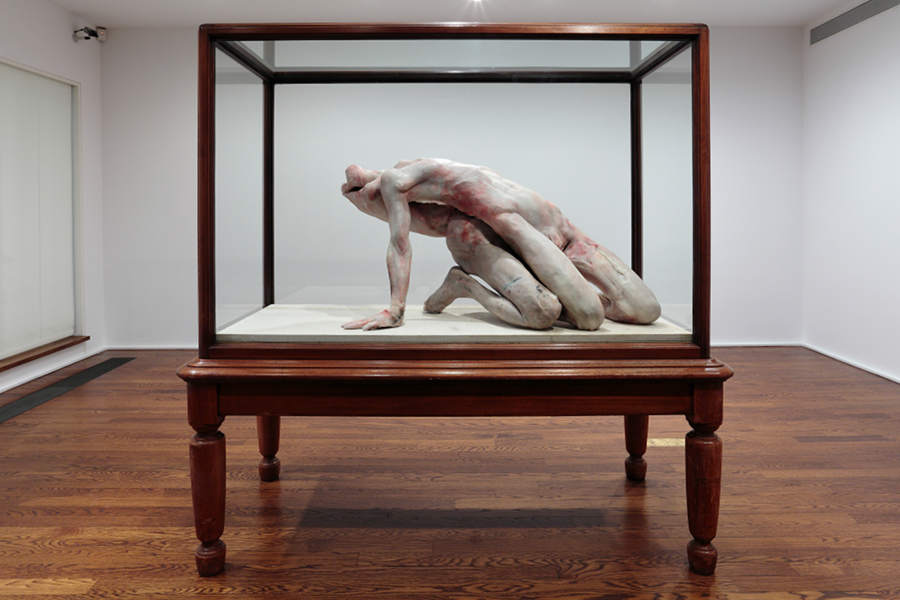

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Into One-Another III To P.P.P. (2010)

Wax, epoxy, iron, wood, glass

Photo: Thomas Müller, courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Berlinde de Bruyckere: Into One-Another To P.P.P

Hauser & Wirth32 East 69th Street

New York, NY 10021

March 1 - March 23, 2011

Interview with Berlinde de Bruyckere

Berlinde de Bruyckere is an aesthetic idol, a translator of human emotional range. Her most well-known sculpture melds organic forms with the figure to bely strain or inhibition of the respective components. She is an activist at heart, truly agitated by the horror and extremity all too prevalent in the world. Even in its decrepitude, de Bruyckere embraces and recognizes the clutches of love that facilitate a timeless, tragic balance. Her showing at Hauser & Wirth is unique in that it exhibits her drawings and sculpture together for the first time. The drawings reveal the spectrum of pure emotion, complimenting the sculpture's more tactile and organized forms while drawing out both mediums' intensity. I spoke with de Bruyckere at the opening of her show on March 1st.

Lynn Maliszewski: I wanted to talk first about your drawings. You have never shown drawings and your sculpture together, and you've presented three distinct vignettes of drawings in three different rooms here. Could we walk through them?

(On the first floor, Berlinde and I meandered toward three drawings all entitled The Wound, 2011)

Berlinde de Bruyckere: For me, that was the only way to do it, to put these drawings together in this room with that piece [Into One-Another II To P.P.P. (2010)]. At home, at the studio, they were always together. The way this work exists now, there are so many reds in the surface, it's because these drawings were behind the work when I was making this. This is the topic of the work. I was not thinking before of something figurative, it was really to draw an emotion, pain.

(Berlinde and I ascended the stairs to Hauser and Wirth's second floor, and paused at the first set of pencil drawings, all entitled Romeu, 'my deer'.)

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Romeu 'my deer, series, circa 2010—2011

Collage, watercolor and pencil on paper.

Photo: Thomas Müller, courtesy, the artist and Hauser & Wirth Gallery

In the exhibition, I had to have this group of pencil drawings here, and not in relationship with the sculpture because these are figurative and if you have them next to figurative work they become studies, and they are not. They are independent. This is the new topic for the future. I work with Romeu, my model, and then out of his head, body, you can see antlers are growing. The whole big topic in this exhibition is being destroyed by your own desire. Usually the deer uses it [antlers] to seduce the female deer, where it's something to be proud of. Here it's completely the opposite: the antlers destroy the human body. In some of the drawings they are growing back inside the body and they hurt him. It's all about being destroyed by desire.

Maliszewski: Are the branches a similar paradox?

de Bruyckere: Yeah, that metamorphosis is from Ovid. The human body is transformed into a tree, and this one now is also from Ovid where Diana Actaeon transforms into a deer. The movies of Pasolini were the biggest inspiration for this body of work and it's the same thing.

(The last group of drawings are all Untitled)

Maliszewski: This last group of drawings work with reds similarly to those downstairs but are much more abstract. Are they related?

de Bruyckere: They are a little bit in-between them. They're very emotional. You can recognize a head behind the tendrils, but you're not sure. This red can also be like the antlers growing out of my head. They are much too small to be antlers but they can also be branches or veins or intestines or something growing out of you without control; you can't stop it. In a way it's covering the face but also destroying the whole head.

Maliszewski: Have you read the Metamorphosis? I like that the characters are in transition, in the experience, versus at one of the two extremes. Is your inclusion of collage in the pencil series coming from this same instinct, to push your drawings into flux?

de Bruyckere: Yes. I did it very often but a long time ago in the first series of drawings that i did in the late 80s or beginning of the 90s. Then I stopped collage and got into color drawings with pencil. They came up again because, from a practical need, I was looking for a deep black and on this type of paper there was only one possibility and I thought I needed more. Then I thought to make part of the drawing on another piece of paper, glossy paper, and then I was also able to use the red paint on the other paper as well. To complete the drawing it was very important to me to have the different colors, different papers.

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Romeu 'my deer', circa 2010—2011

Collage, watercolor and pencil on paper

Photo: Thomas Müller, courtesy, the artist and Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Maliszewski: Both themes and visuals are recycled in both your sculpture and drawings. How do you function through repetition?

de Bruyckere: I very often use the same topic. It means I have a theory. I get this feeling that something is growing out of the head, and one way growing back into the body. That was one way that I was showing the drawing of the body. Then I needed some other ways to do the same to make the whole series. Like the last two pencil drawings: they look very close to each other except for one small movement but it means I was not satisfied by one so I did a second one just to have both to complete the scene. It makes it more universal. It's not a personally related work, it's more about how we suffer in general and the larger universe. So for that you need more work. If there's only one work, it can only be directly related to myself.

Maliszewski: So the more prismatic your output is, the more potential there is for its reception. Why are your sculptures hollow in this show?

de Bruyckere: This show is the first time in this group of work that it is so visual that they are carved out of different bodies. Before they were bigger and we closed the front and the back. Here I deeply needed to show you the insides and how hollow and black the insides can be. It's a metaphor for emptiness and loneliness in a way. I was thinking about black holes, where all knowledge goes in and we can never get it back. There's a lot of meaning in the black hole.

Maliszewski: Interesting to think about that in the scope of memory, which despite our grasp of it will inevitably degrade and decay over time. Like your bodies, the structure is still there even if the insides, the meat, is completely gone. Is there any subject that's off-limits for your contrasts of sentimentality?

de Bruyckere: I think in this show I am very open and I show a lot of very difficult issues and topics. It's not something to be proud of. What happens in the works themselves is something very brutal in a way. The direct connection with the movies of Pasolini is reduced into those works. I can't say if I can't go further or that this is the limit. It happens only for a moment that I was able to liberate myself and show this without fear, without anger, without doubt. I know there are very few secrets in this exhibition. It's all about showing your emotions in a very open way. I don't know how far I can go.

Maliszewski: How do you personally challenge yourself?

de Bruyckere: This collaboration with Pasolini was very intense. It took a lot of time to do research on movies and plays and literature. He lived such a life. There was not really time to let in anything else during the last two years. I didn't read any books by other authors because i have to limit it for myself. It's not possible to combine. He is such a complex and difficult person that to combine all this then to reduce it into working terms was already such a big topic. When I need to escape from this, I really want to go into nature or do nothing or cook for my family. There was no other way to escape, I couldn't go to this movie or that book.

Malizewski: Do you see yourself always utilizing the figure?

de Bruyckere: I don't say that I will forever use the human body. I use it because it's an extension, like you extend the intestines and it's fleshy and big and hard at the same time. There could be nothing from the human body inside yet it's talking about human feelings. It's not that I really need the body to tell you something about the human condition. I do it very often with horses. There's one work at the Armory with my other gallery, Continua, in Italy and they are showing a small horse. For me this is like one of Pasolini's movies where Medea kills her child and she is laying it on the table. For me that was exactly the thing. Taking the child and leaving it on the table. I don't always need the human body to talk about humanity.

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Wounds Series, all Untitled (2011)

Watercolor and pencil on paper

Courtesy, the artist and Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Berlinde de Bruyckere, Untitled (2010)

Watercolor and pencil on paper

Photo: Thomas Müller, Courtesy, the artist and Hauser & Wirth Gallery

Lynn Maliszewski

Lynn Maliszewski is a freelance writer and aspiring curator/collector residing in New York City. She can be reached at l.malizoo@gmail.com

PHOTO CREDIT: Benjamin Norman (www.benjaminnorman.com)