Whitehot Magazine

February 2026

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

February 2026

December 2013: GUGLIELMO ACHILLE CAVELLINI

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Crate No. 87 (Cassa N° 87),

1966, 21¼ x 16½ x 4 inches (54 x 42 x 10 cm), Courtesy LYN CH THAM

GUGLIELMO ACHILLE CAVELLINI (1914 – 1990)

18 September to 27 October 2013

175 Rivington Street, New York, NY 10002

LYNCH THAM, in collaboration with the Archivio Cavellini

By Mark Bloch

For those of you who do not know, Cavellini was a wealthy Italian art collector who decided to distinguish himself and create his own art form so he invented the art of "autostoricizzazione" or self-historification. “Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, 1914-2014” (to commemorate his centennial) was damn funny and his prescient art form skewers the bloated excess of the current art market like a much-needed and well-placed Groucho Marx one-liner. This show on the Lower East Side of Manhattan has given us one last chance to look at him and his work before his international centennial retrospective year.

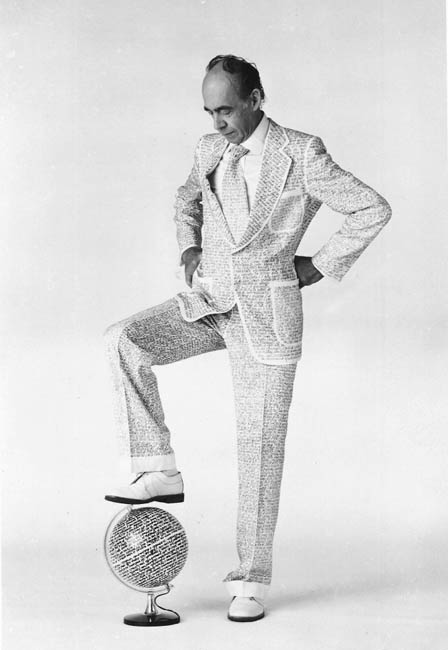

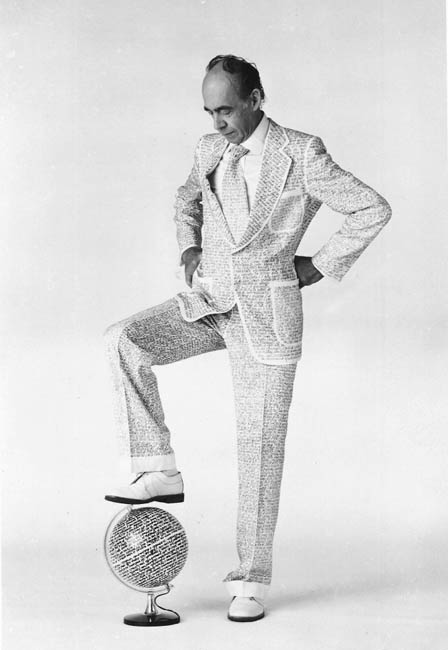

Cavellini began, in the early 70s, to write his autobiography by hand in his distinctive handwriting with a felt tip marker anywhere he could—on naked models, globes, and other objects as well as on clothes which he would then wear. He began to compile exhibitions of his work and publish them in beautifully made books and catalogues that were translated into several languages. He would then send these books to anyone who asked in elegant packaging and consider them a "living room exhibition" because they were one-man shows of his work that took place for a limited audience (the recipients) in people’s homes across the world. With this technique he soon catapulted himself to #1 status as the artist in the world featured in the most shows. He loved the Italian flag tricolors and used them in his work and created the "Cavellini sticker" which was a round industrial quality sticker in red, white and green that bore the dates of the fast approaching Cavellini Centennial: 1914-2014.

He also sent these stickers all over the world and they began to appear in odd places. There might be one aging on a stop sign in a small American town having nothing to do with the maestro. A person might casually glance up and see one towering inexplicably far above eye-level on a building, billboard or telephone pole. A power box on the George Washington Bridge or a rustic signpost on a nature hike somehow, somewhere might be adorned with one. It made no sense but they seemed to pop up with uncanny frequency in the early 1980s. People would also cover themselves with them (as occasionally would he) for the occasion of a photograph that would then travel the world by mail. Cars and other objects could be seen wrapped in them, particularly when he was scheduled for a visit, which were always events calling for great fanfare. Once I wrote to him asking for "a couple thousand stickers" and a week later some packages arrived at my door containing 2000 stickers. I had become aware of him as I ventured into the international postal art network in the late 1970s.

I met him three times, in California in 1980 (where, at Interdada 80, he was reportedly heralded as the King of Alternative Art at a Punk Prom in East L.A. where a performance by the band “X” preceded his crowning) and ‘84 and then in New York in ‘82. Cavellini was one of the first superstars of mail art, that genre which is not supposed to have superstars. An “artistic mail dialogue” in the early 70s with fellow reluctant superstar Ray Johnson, the founder of correspondence as art, eventually led to worldwide network exposure for Cavellini, who was finally reaching the audience he had long imagined. A generation of younger artists, including myself, mythologized him, identifying with his systematic mission of self-historification in an era of cacophonous voices screaming from within and without the art establishment, “Look at me, look what I did!” As the auto-historifying founder of his own cult of personality, he not only created an appearance that he invented mail art but also fire, string cheese, string theory and sliced bread, in addition to discovering America, developing the Theory of Relativity and being the first man on the moon.

Cavellini with the author in the 1980s Courtesy Mark Bloch, P.A.N. Archive

Cavellini with the author in the 1980s Courtesy Mark Bloch, P.A.N. Archive

Despite the fact that he created a postcard in 1975 that issued a list of “Ten Ways to Make Yourself Famous,” one of which was "Kill Cavellini or have Cavellini kill you," the Maestro died of natural causes in 1990, a few months after I had to cancel a scheduled visit him in his northern Italian town of Brescia due to his ill health. But since Number VIII on that list was “Write a book or an essay on Cavellini,” with your assistance, dear reader, I will now consider myself extremely well known, important or at least permanently historified as a result of the document you are currently reading.

I heard in mid September there was to be an opening of GAC’s work on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. When I entered the LYNCH THAM on Rivington Street, I did not expect to see what I did. Quite unlike the scruffy underground audiences of yesteryear, the small but magnificent gallery was packed with nicely dressed art world types, admiring the art and watching performances with even GAC’s handsome lookalike heir, Pietro in attendance and representing directly his father’s distinguished Archivio Cavellini. When I cut through the glamorous ambiance and looked at the walls, even more shocking to me was the fact that this was a show of several of Cavellini’s famous masterworks from the 1960s and ‘70s that I had seen only in photographs. For an old fan, this dream come true was an entirely new Cavellini experience for a new millennium.

The works on the wall here in 2013, the year before the rapidly approaching Cavellini centennial, were mostly elegantly constructed crates containing destroyed works. Cavellini came to destroying his own artwork after what he called some “frantic artistic experiences.” His perception was that he was “surrounded by a collector’s notoriousness” and that his work was “regarded with suspicion.” The story begins at the end of World War II, when Cavellini started painting in earnest. Because cultural influence was scarce in the provinces, in ‘46 he began seeking the friendship of the best Italian artists of his generation. In ’47, he went to Paris and was dismayed to find that everything he was trying to do had already been done—by others. He thus gave up painting and went to work for his rich father, reportedly an owner of supermarkets, and became a collector of contemporary Italian paintings. Any art discovery he’d have liked to create himself, Cavellini bought, transforming every purchase into a creative act. By the 1950s Achille, as he was known, became interested in international art when his Venetian artist friends led him to Peggy Guggenheim’s famous collection overlooking the canals of Venice. Dazzled by her Jackson Pollocks, he contemplated buying a few despite their high price, but needed time to think. While he waited, Pollock died, so he next turned to Franz Klein, Gottleib and later Twombly. Thus did Cavellini move from the Italian abstractionists, including the Group of Eight, to collecting Burri, Dubuffet, Lucio Fontana, Hockney, Asger Jorn, Lichtenstein, Matta, Manzoni, Rauschenberg, and eventually the Nouveau Realists.

Teatro-dell Autostoricizzazione courtesy Archivio Cavellini

Teatro-dell Autostoricizzazione courtesy Archivio Cavellini

Germany’s first Documenta in 1955 featured over two dozen works from his freshly acquired collection. Next hundreds of his pieces traveled to Rome, where Palma Bucarelly exhibited much of his collection in her “Nazionale” Gallery in ’57, drawing great fanfare. His works then traveled to Swiss and German museums as well as Basel and France. He wrote a book on abstract art in ‘58 and then in 1960 documented, in words, his artistic relationship with the late Renato Birolli, an abstact painter from Verona and one of the founders, in 1945, of the "Fronte Nuovo delle Arti” (New Arts Front), artists who had previously been bound by fascist rule. Ironically, it was this book that led to Cavellini later documenting a fictitious “collaboration” with van Gogh and later the likes of Marx and Nietzsche. Cavellini was about to become a full time artist again when the books and then articles in art magazines about his friendships with painters did not scratch his itch.

In ‘62 when he finally picked up a brush again, the art world had transformed to Pop Art, Fluxus and Happenings. In 1965 he said, “I warily attempted a summary neo-Dada experience” at Milan’s Apollinaire Gallery, where the Nouveau Realistes, Europe’s version of the Pop, had debuted five years earlier. By 1970, his works would be destroyed and Cavellini would dedicate one of his “Carbone” series, a “charred gears” sculpture, to the Nouveau Realist Jean Tinguely.

Looking back on Cavellini’s collecting, the Italian critic Marco Meneguzzo said, “In reality he collected the brushstrokes or in other words, the actions of the artists. And so when the brushstroke was freed from the support and became action, happening, performance from which the object, the work, emerged—or might emerge—as residue of event, Cavellini was ready.” Indeed, Cavellini once said, “One may become a collector, but one can only be born an artist.”

So from 1966 to ‘70, Cavellini embarked on the systematic destruction of his own paintings in the eventual form of “Crates with Destroyed Works.” In addition, from ’66 to ‘68 he was quoting other people’s works and appropriating them in wood and colored Plexiglas as well as creating a more joyful “celebration collection” in the form of “Wooden Postage Stamp” images in which, according to one critic, “inserting them into massive wooden inlays, he enlarged their objective presence.” He combined geometric abstractions of chromatic scales with maps of Italy, which became a personal symbol to him. But, disappointed by the half-hearted welcome Cavellini detected towards his return to art making, he faced the contradictions of the art system head on.

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Writing in black and red mark er on paper (Scrittura a pennarello rosso e nero su carta),

1975, 18¾ x 18½ x ¾ inches (47.5 x 47 x 2 cm), Courtesy LYNCH THAM

In the late ‘60s and early ‘70s he invented his “Carbones” in which the purification of burning destroys the past. But he stated in 1970 that, “I never had the courage to destroy them altogether.” Wielding a jigsaw as well as a blowtorch, he used old works to create new homages as wood compositions replete with gaps and holes, halfway between paintings and carvings or as Dick Higgins, a Fluxus originator might call them, Intermedia, that important buzz word of the day referring to a destruction not of works but of boundaries between genres. Cavellini further sawed up and burnt the already destroyed hybrid 2D-3D works, always succumbing to the desire to preserve them somehow, “as though they were priceless relics.” But still dissatisfied, these were themselves further broken down then reconstructed as boxed “cages” in which the destroyed works can be seen behind wood slats. His inkling for preservation, reconstructing and “re-proposing” in spite of his desire to destroy, led him to an attempt next to dispel the preconception by critics, real and imaginary, that he was a “painter-collector” and not a “collector-painter.”

Cavellini longed for a “year zero” of his painting when he could begin anew to build over the ruins of his former life. By 1971, Autostoricizzazione was born. He said, “What shows though most of my works is irony, stimulated by a bit of bitterness” caused by “voluntary seclusion.” In 1968, he had positioned his face over that of Lenin in a collage and liked what he saw. Three years later he designed 16 museums posters he later called “manifestos,” commemorating his own centennial celebration in 2014 at the world’s greatest museums and then created mock banners declaring the same, shown hanging outside of Venice’s Palazzo Ducale and Rome’s National Gallery of Modern Art. It was the former that went on to become a trademark via the now-famous Cavellini sticker. As long as he was inventing things, why not also document his relationships with historical figures as he had with the artist Birolli? Thus was his first imaginary correspondence with Van Gogh depicted on canvas, followed by fictitious books commemorating suggestions by him to Karl Marx and Fredrich Nietzsche. A 1973 Universal Encyclopedia entry described meetings with Mao, winning the Nobel Prize, trips to the moon, shows at the Tate and MOMA and finally his discovery of a new color, which he donated to the rainbow, no less.

In 1974, Cavellini traded art work for a portrait by Warhol during the latter’s trip to Europe and Cavellini used that to finally propel himself unstoppably into an art form that few had ventured into as wholeheartedly up until that time but that many have embarked on since: self promotion. “I regard my painting as autobiographical” stated this “Narcissus from Brescia” in his “diary of the genius” but a sly hint of self-parody cut through the audacious obnoxiousness of his shameless self promotion creating an art form whose time had come. Cavellini had a postage stamp made of himself, Warhol and the portrait that traveled around the world.

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Written names in marker on cardboard (Scrittura nomi a pennarello su cartoncino),

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Written names in marker on cardboard (Scrittura nomi a pennarello su cartoncino),

1975, 3 5 x 23½ x 1¼ inches (89 x 60 x 3.5 cm), Courtesy LYNCH THAM

By considering that every carefully wrapped package of his various books that he had sent by mail in a cardboard portfolio as a separate exhibition, Cavellini calculated that by Spring 1976 he had held 10,600 shows including all the worlds most important museums. He contacted Art Aktuel editor Dr. Willi Bongard to talk him into correcting the Kunstkompass chart assembled annually creating a hierarchy of the most exhibited artists. Cavellini was at the top, over Rauschenberg. He also created a list of the top artists in history and their contributions positioning autostoricizzazione between the Fluxus artist George Brecht’s event-scores and Dennis Oppenheim’s and Walter de Maria’s land art.

In the spirit of Fluxus as well as Ray Johnson’s New York Correspondence School, New Realism’s sarcasm, the Theater of the Absurd and other neo-dada shenanigans, Cavellini wrote about himself with great superlative flourishes and every stop removed for posterity on walls and clothes, and eventually our collective memory. A new series of books followed. This was around the time that he became a hero of the burgeoning mail art network so any hint that he was lacking in the humor department was soon usurped in the form of hilarious irreverent homages in which his own image, his story and his alleged accomplishments as well as that of the Cavellini sticker were used as the raw material for parody, ridicule and mayhem on an international scale.

So what I saw for the first time in the LYNCH THAM Gallery almost 50 years later was both his legendary destroyed works in crates and early examples of his autobiographical writing activities:

His Crate No. 87 (Cassa N° 87) from 1966, reveals pieces inside that look like they were cut out cleanly by a jigsaw but mixed with an occasional few that looked broken by hand. Similarly, an occasional stripe stands out amongst the green, blue, white, and unpainted pieces with the unpainted echoing the raw wood crate that enclosed it all like an envelope, a delivery system for twice-crated, thrice-created art of destruction as well as preservation.

The beige, black and white Italy-shaped puzzle pieces of Crate No. 131 (Cassa N° 131) emblazoned with the stenciled lettering “Contiene opera distrutte” give the impression of camouflage. Should I see this more geometric 1967 work as it is or should I mentally try to unscramble and reconstruct the elements as in a game?

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Crate No. 114 (Cassa con Bruc iatura N° 114),

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Crate No. 114 (Cassa con Bruc iatura N° 114),

1969, 30 x 30¾ x 3 inches (76 x 78 x 8 cm) , Courtesy LYNCH THAM

The Crate with Burnt Wood No. 114 (Cassa con Bruciatura No. 114), 1969 has burned sides that flank and highlight an uplifting colored middle. Burning carved wood appealed to GAC most of all, because the charred black made the “vividly-painted” colors pop out: reds, purples, browns, two blues and in the center unstained wood. The charred areas frame little squares within squares like mini-Rothko or Josef Albers works.

In the Italy postage stamp on a red background, carbon the subject matter transcends the message that it presents a country let alone a stamp, as the charred provinces of Italy, clearly demarcated, create a linear national map that would be a flat carrier of its semiotic power to symbolize except for the minor detail that it is anything but flat. Thick pieces of worn, burnt wood cast smooth shadows and create contrast with the repetitious surrounding “perforation” pattern in beautiful black and white. Concentric halos of texture and color then emanate out from the geographic center in the form of a raw wood border, which in turn populates a red outer frame.

Finally, tucked away on a back wall, in Crate No. 236 (Cassa No. 236) a gorgeous diagonal cut dissects the piece as well as its contents in 2 layers. With holes drilled in the pink, magenta, yellow and red pieces—with one flesh colored—a puzzle pre-solved offers itself to me without the enigmatic edginess of the other works in the show. This is all served up on a blue background fixed with tiny nails. It is exquisite.

Toward the front of the gallery, Cavellini’s Homage to Lichtenstein (Omaggio a Lichtenstein) stood as the lone example here of his 1966-68 works that followed the crates and quoted other artists. This one is a send up of Roy Lichtenstein’s 1965 pop art painting Girl With Hair Ribbon from the pop artist’s comics period, when he painted nothing but close-ups of women, creating overpowering and highly stylized images of pure femininity out of the beauty of the female face. Lichtenstein had removed the woman from the context of the comic but retained some of its narrative qualities with the cartoon subject’s ambiguous expression between longing and fear, leaving the viewer with a mini-story fragment. A mere three years later, in this 1968 work, Cavellini, by screwing Lichtenstein’s painting into a board mounted on black enamel, and carefully covering the image with strips of red Plexiglas, completely destroys the context of the Pop artist’s low brow appropriation and turns it into a symbol of the glut of ‘60s pop iconography devoid of all meaning other than its campy function as an artifact of high brow art making in the very expensive psychedelic era still in progress at the time. Anticipating the self-historification he would invent a few years later with this gesture, Cavellini had reduced all precious art objects to nothing more than props to illustrate the more notable and more interesting narrative arc of art history itself.

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Homage to Lichtenstein (Omagg io a Lichtenstein),

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Homage to Lichtenstein (Omagg io a Lichtenstein),

1968, 35¾ x 37 x 1¾ inches (91 x 94 x 4.5 cm), Courtesy LYNCH THAM

There were either three or four groups of works in this show: the crates and this lone example just mentioned that appropriates his fellow artists. And some examples of the burned works known as “carbones.” Nevertheless, the final one is the early writing works called From the "Page of the Encyclopedia" from 1973. I had been written on myself by the master but seeing these early manifestations was certainly a treat.

Written names in marker on cardboard (Scrittura nomi a pennarello su cartoncino) from 1975, contains surnames I recognize like Descartes and Modernism’s Eduardo Paolozzi and Schoenberg as well as influential post-modern masters like Allen Kaprow, John Cage, LaMonte Young. Figures such as Maurice Estève and Jean Bazaine are less familiar to this American. Still, every name achieves fame when it is written by Cavellini and perhaps even more when it is scribbled out as these all were.

A scripted 1973 five by four foot visual poetry work titled Text on Canvas (Scrittura Su Tela) has the artist’s name in all caps, each letter a different color, stenciled like a rainbow across the top of the canvas creating some magic to the somber black writing in Italian below which is actually two texts, one large and one small, that comprise the body of the work with the first word in both being Cavellini, of course, “drawn” like so many of his text works, in marker.

In Writing in red marker on metal (Scrittura a pennarello rosso su metallo) from 1974, indeed there is metal, there is marker and it is all in a wood frame harkening back to the destroyed works in crates that surround it. A single set of uniform letters float in all their felt tip glory creating a contrast with the permanence of the metallic surface they adorn.

The Writing in black and red marker on paper (Scrittura a pennarello rosso e nero su carta) from 1975, is tiny and delicate by comparison with hand writing that changes color but continues right through the square in the middle on textured paper invoking the name of Mao Tse Tung at one point to remind us that these are Cavellini’s imaginary autobiographical meanderings as well as an understated but sophisticated visual work reminiscent of Asian calligraphy.

Guglielmo Achille Cavellini, Text on Canvas (Scrittura Su Tela),

1973, 58 x 46¾ inches (147 x 119 cm), Courtesy LYNCH THAM

Finally, by contrast, Heirloom, Text on Felt (Cimelio con Felta Scrippa) from 1973 couldn’t be more Western. It looks to me like a cheesey off-white shirt with elastic banlon sleeves behind glass with some of GAC’s story written on it. If it looks that way to me, what of the uninitiated? And why cheesey? What do I know of the value of such things? Knowing the impeccable taste of Cavellini and Italians in general it was probably a very chic and pricey item at the time. Regardless, GAC wrote his bio here as he did on skirts, suits, hats, umbrellas, you name it. Did it really matter conceptually where he wrote it or if it was even him who did so? Surely to collectors it did. In the window of this gallery on the glass, there was even an artist’s rendition, a hired hand, as it were, attempting to approximate GAC’s famous script that aspired to elevate handwritten text to a meta-artform not because of its content but due to its quantity, it’s excess. Self-obsessed text that refuses to feel foolish, text that foreshadowed the overexposed public personas of Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons or even Kanye West while creating an art world equivalent to the charming narcissistic braggadocio of Mohammed Ali, Cavellini’s mid-century contemporary, at his peak.

Unlike so many other art forms, the world would not have needed to invent "autostoricizzazione" because it has always been around in various forms but Guglielmo Achille Cavellini rescued it from tedium with style and a much needed sense of humor. He did so in the context of the various intersecting art worlds, a special zone where hubris knows no bounds. 2014 can at last be a year not of self-historification for Cavellini but of historification and appreciation by us all for a once-frustrated one percenter who chose, in the end, to create, not collect, and found his way by taking not the road less traveled but one even overused during his own time and today in need of some serious examination and a major infrastructure overhaul. I said when Cavellini passed away that he died for our sins, or at least our egos. He would have liked to have saved humanity but instead he made the world safe for humility.

Mark Bloch

Mark Bloch is a writer, performer, videographer and multi-media artist living in Manhattan. In 1978, this native Ohioan founded the Post(al) Art Network a.k.a. PAN. NYU's Downtown Collection now houses an archive of many of Bloch's papers including a vast collection of mail art and related ephemera. For three decades Bloch has done performance art in the USA and internationally. In addition to his work as a writer and fine artist, he has also worked as a graphic designer for ABCNews.com, The New York Times, Rolling Stone and elsewhere. He can be reached at bloch.mark@gmail.com and PO Box 1500 NYC 10009.

view all articles from this author