Whitehot Magazine

October 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

October 2025

Teresa Burga at Alexander Gray Gallery

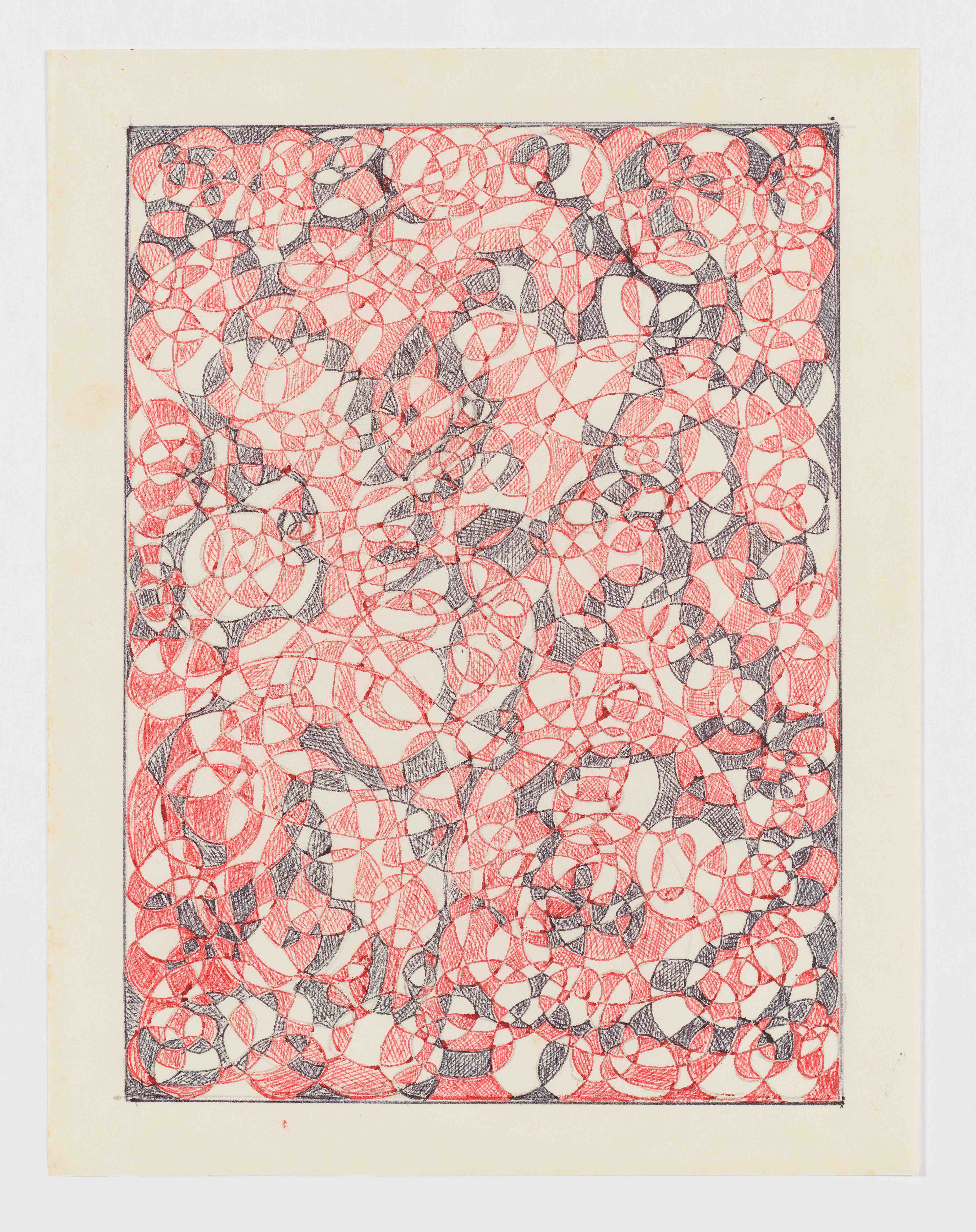

Teresa Burga, Insomnia Drawing 14, 1990. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Teresa Burga, Insomnia Drawing 14, 1990. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

September 5 - October 12, 2019

By JONATHAN GOODMAN, October 2019

The Peruvian artist Teresa Burga, now in her eighties, has a very good show on currently in Chelsea. Educated both in Peru and in America (she received her master’s degree from the Art Institute of Chicago), she returned to her native country in 1970, where she has made work sympathetic toward women and those opposed to rightist currents there. Her art--her drawing especially--tends to be abstract; many of the strongest pieces are the current small, elliptical drawings in which very small spaces, outlined in black, are filled in with color, usually with black and red (there is a large black-and-white drawing, constructed similarly, done on a single wall on the second floor of the gallery). There are, as well, two decorative sculptures, about lifesize, made of steel; and on the first floor, several small, very colorful works celebrating women from indigenous cultures. Together, the various pieces amount to a minute retrospective of an artist whose work emphasizes both nonobjective form and social change.

We know from her life events, and to some degree her art, that Burga has been an activist, but the majority of her pieces in this show are abstract, and communicate an interest in form rather than political circumstances. In regard to her experience, this pushes her audience a bit in the wrong direction; we cannot suggest that Burga is only a formalist. Indeed, her leanings have been sharply politicized from the start. But the abstract work, which is excellent, cannot easily communicate an idiom oriented toward the social collective, even if we associate certain kinds of abstract work--the art of Russian Suprematism and Constructivism, in particular--with the left. In the case of Burga, it becomes clear that her art participates in a modernism that was relatively new in the 1930s, the decade in which she was born; and that, even so, her abstractions represent a highly accomplished understanding of nonobjective work while working within an imagination oriented toward ongoing disagreement with (male) power in Peru.

Teresa Burga, Insomnia Drawing 23, 1990. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Teresa Burga, Insomnia Drawing 23, 1990. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Burga’s artistic life in Peru after graduate school was constrained by limitations regarding women showing their art. Indeed, both the sculpture and the wall drawing were not realized until this show. It is excellent that she is receiving attention in America, where surely her graduate education in Chicago helped her develop as an artist. The small abstract pieces radiate technical skill and the enjoyment of pattern. Insomnia Drawing (23) (1990), a series of curving interlocking forms in a small composition created with red and black pen, shows how careful Burga is building form out of smaller form. The precision in the work is evident at first glance, giving her audience a sense of carefully constructed space and an overall, interlocking design that is harmonious, pleasing. It is echoed in other drawings next to it--including Insomnia Drawing (14), also from 1990. Here the forms defined, again, by black and red pen are not so dark or so curvilinear. But they too fill a small space, in which the white of the paper, like the white of the first drawing described, comes across as a distinct element on its own. On a regular basis, then, the artist shows a preference for involved patterns, whose spaces collide with each other. This is seen as well in the large black-and-white abstract work realized on the wall, whose outward edges contain scores and scores of spaces, dark and light, that take over the flat plane of the facade.

Teresa Burga, Serie Maquinas Inutiles Florero, 1974. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Teresa Burga, Serie Maquinas Inutiles Florero, 1974. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Beside the abstract drawings, the two welded steel sculptures--Florero (1974/2019) and Lampara (1974/2019)--stand out. Both incorporate a vertical structure through the use of thin metal strips; Florero ends above in a series of flower shapes, while Lampara is composed of three pieces--a slightly angled base leading to a bulging middle, with a more open top. In each of the three parts, the surface of that work is nearly closed by leaves, which lend a decorative aura. In both cases, the structure is both well-balanced and open. These works are accompanied by drawings from 1974, which detail the exact sizes of the dimensions of each piece. It is particularly useful to see the relations between the imagined work and its realization; we remember that Burga is an excellent draftsperson, and that she tends to rely on patterning to make her art work.

Teresa Burga, Serie Maquinas Inutiles Lampara, 1974. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

Teresa Burga, Serie Maquinas Inutiles Lampara, 1974. Courtesy Alexander Gray Gallery

The most recent work, on the entrance floor, consists of small, colorful drawings of Andean women. One shows two women wearing hats and dark clothing and sandals. They stand against an alpine landscape, alternately green and black, with a dark blue sky topping the composition, just above a brilliant blue peak. Another drawing is of one person: a woman wearing a red hat, with a dark, red top and black skirt, stockings, and shoes. The lower background is white, taken up with tiny black spots, while the upper register consists of jagged stripes, mostly horizontal, in green. These brightly hued drawings indicate Burga’s interest in the material culture of marginalized women of indigenous background. The works demonstrate the artist’s skill as an octogenarian; they show her ongoing interest in those sidelined by gender. But the earlier work also presents her achievement as a modernist of distinction. Combined, her interests establish two worlds: one of visual pattern and one of political interest. WM

Jonathan Goodman

Jonathan Goodman is a writer in New York who has written for Artcritical, Artery and the Brooklyn Rail among other publications.

view all articles from this author