Whitehot Magazine

December 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

December 2025

August 2013: Alexis Smith @ Honor Fraser Gallery

Alexis Smith, Golden Glow,1995. Mixed media collage, leather. Installation dimensions variable, Panels, 29 x 24in.

Alexis Smith, Golden Glow,1995. Mixed media collage, leather. Installation dimensions variable, Panels, 29 x 24in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith: Slice of Life

Honor Fraser Gallery, Los Angeles

June 8 to July 27, 2013

by Megan Abrahams

Alexis Smith is an artist who wears many hats. Her medium, collage, is the product of being herself a collector and an archivist – in essence, a curator of specially selected objects each embodying their own stories and references. Using these objects as points of departure, Smith reawakens them, combining and re-contextualizing them, inventing for them new narratives rich with her own wit and irony. In Slice of Life, she has re-envisioned slices of other people’s lives, embellishing a series of found portraits, record covers, vintage advertisements and a compendium of visually resonant images from thrift shops and various sources. Smith makes them her own by adding text -- such as excerpted dialogue from the movie Dr. Strangelove -- and juxtaposing carefully chosen fragments and seemingly unrelated objects, imagery and found material in her own signature brand of assemblage. Ornate custom-made frames literally provide new frames of reference for the once-familiar, adding dimensionality and visual continuity.

At a presentation during the run of the show, Smith spoke about her work in a conversation with writer Amy Gerstler, with whom she collaborated on the 1989 installation, Past Lives. She described the portraits, record covers, advertisements and other illustrations she has used as backgrounds for her collages as, “other people’s work cannibalized by me. It’s something to have a signature style that relies on people you don’t know,” she said. Collecting just the right objects, and having amassed such a collection, is an important part of her creative endeavor. “I used to be a real scavenger. I used to really look for stuff. I have a big wealth of materials now. Sometimes people give me things. I get them at garage sales. It’s a process,” said Smith. Gerstler recalled visiting the artist in her studio several years ago, before Smith moved to a new space. The place was a treasure trove of all kinds of found objects -- everything from tubas to jewelry. “It was like ten thousand grandmas’ attics.”

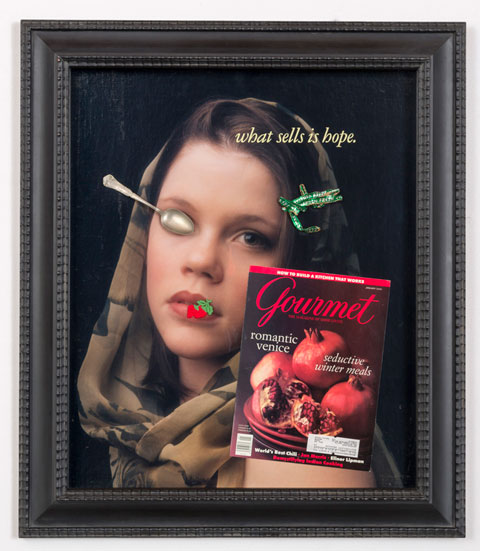

Among the materials Smith most prolifically collects are ripped advertisements and other illustrations, which must wait, sometimes years, for their rehabilitation. Smith explained that she doesn’t rush to glue the pieces together. “I let them sit there for a long time before I formalize them,” she said. “I try to make the background and the object relational, so they’re moving in the same direction.” The background of her piece, Forbidden Fruit, (2001) is a portrait of a woman. Smith has superimposed the inscription, “What sells is hope.” An actual spoon is stuck on top of the woman’s eye, obscuring her vision. Affixed in the foreground is the cover of a January 2000 Gourmet Magazine with the feature, “Romantic Venice, Seductive Winter Meals.” An intact mailing label with Smith’s own former Venice, California address is still attached to the magazine. Despite the superficial incongruity, the composition has a satirical harmony -- and that dynamic of tenuous balance is largely what Smith’s work is about, and from where its power derives. The centerpiece of the triptych, Family Values, (2009) is a portrait of a woman, whose face Smith has covered with a lace doily. The portrait of the male on the right has a black eye patch rakishly stuck over one eye. The portraits -- along with whatever their original significance may have been -- become secondary after Smith imbues them with new meaning. “They’re not my paintings,” said Smith. “I mean they are now.”

Alexis Smith, Forbidden Fruit, 2001. Mixed media collage, 29 x 25 in.

Alexis Smith, Forbidden Fruit, 2001. Mixed media collage, 29 x 25 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

An ad for a Giorgio Armani necklace is the background for another re-envisioned work entitled Choker (2000). Among the embellishments, superimposed on the ad is a caricature of a medieval character wearing a noose. Also featured in the exhibit are collages built on top of old advertisements, with patronizing images of women like the cowgirl in Here to Serve You. To this, Smith has added a few striking touches -- a chip of mirror on the model’s front tooth catches the light, and fragments of strategic text such as, “Texas Cattle Queen,” “Texas Tender Beef,” and “What’s Your Cut?” The word “rump” is inscribed on the cowgirl’s bottom. Propped on the floor, below the image, is an actual pair of cowboy boots, as if either waiting for the girl to eventually escape from the confines of the image and step into them, or commemorating an independence lost by her immersion in the commercial fantasy of the images into which she has been subsumed.

“I really get a kick out of making this stuff. It’s supposed to be funny, droll, like a little bit of sugar helps the medicine go down. When they amuse you -- you have to understand them to be amused -- you have to look at them or you don’t get them,” said Smith. Her unique perspective may have been influenced by an unconventional childhood. The artist grew up on the grounds of a mental hospital where her father, a psychiatrist, was assistant superintendent. “I think I had an unusual life by today’s standards… I can relate to a broad range of people, and if I make fun of them, it’s good spirited,” she said.

In the adjacent gallery is the accompanying installation, Past Lives, a reimagined classroom, peopled with the artist’s collection of vintage children’s chairs grouped in clusters around the floor. Surprisingly poignant given that these are inanimate objects, the little chairs are worn, empty and seemingly bereft. It is an impressive collection, which includes standout pieces like a small pink upholstered armchair that must have belonged to a little girl, a rocker balanced on a tilt, as though a child just got up from it moments ago, a green metal garden chaise and various wooden chairs that may have once played important roles in a primary school somewhere. Assembled with evident care, the chairs each have a distinct character. They seem to evoke the essence of the children who once sat in them, suggesting long forgotten stories and secrets. Chalkboards and other classroom icons complete the setting. Referencing her work, Smith said, “I think this work looks like nostalgia, but it’s actually anti-nostalgia.” In the tradition of Dada and the Surrealists, Smith digs way beneath that surface.

Alexis Smith, Lonesome-Cowboy, 2002. Mixed media collage, 54 x 40 x 3in.

Alexis Smith, Lonesome-Cowboy, 2002. Mixed media collage, 54 x 40 x 3in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith, Don't Feel Like the Lone Ranger, 2003. Mixed media collage, 24 x 21 x 2 in.

Alexis Smith, Don't Feel Like the Lone Ranger, 2003. Mixed media collage, 24 x 21 x 2 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith, Black and Blue for Howie Long, 1997. Mixed media collage, 29 x 19 x 4 in.

Alexis Smith, Black and Blue for Howie Long, 1997. Mixed media collage, 29 x 19 x 4 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith, Wild Horses, 2012. Mixed media collage, 22 x 24 in.

Alexis Smith, Wild Horses, 2012. Mixed media collage, 22 x 24 in.

Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery, Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith, Past Lives, Installation View. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery , Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Alexis Smith, Past Lives, Installation View. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery , Photo Joshua White: JWPictures.com

Megan Abrahams

Megan Abrahams is a Los Angeles-based writer and artist. The managing editor of Fabrik Magazine, she is also a contributing art critic for Art Ltd., Fabrik, ArtPulse and Whitehot magazines. Megan attended art school in Canada and France. She is currently writing her first novel and working on a new series of paintings.

view all articles from this author