Whitehot Magazine

September 2025

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

September 2025

Master With A Microscope: Jan Hinsch’s Abstract Nature by Donald Kuspit

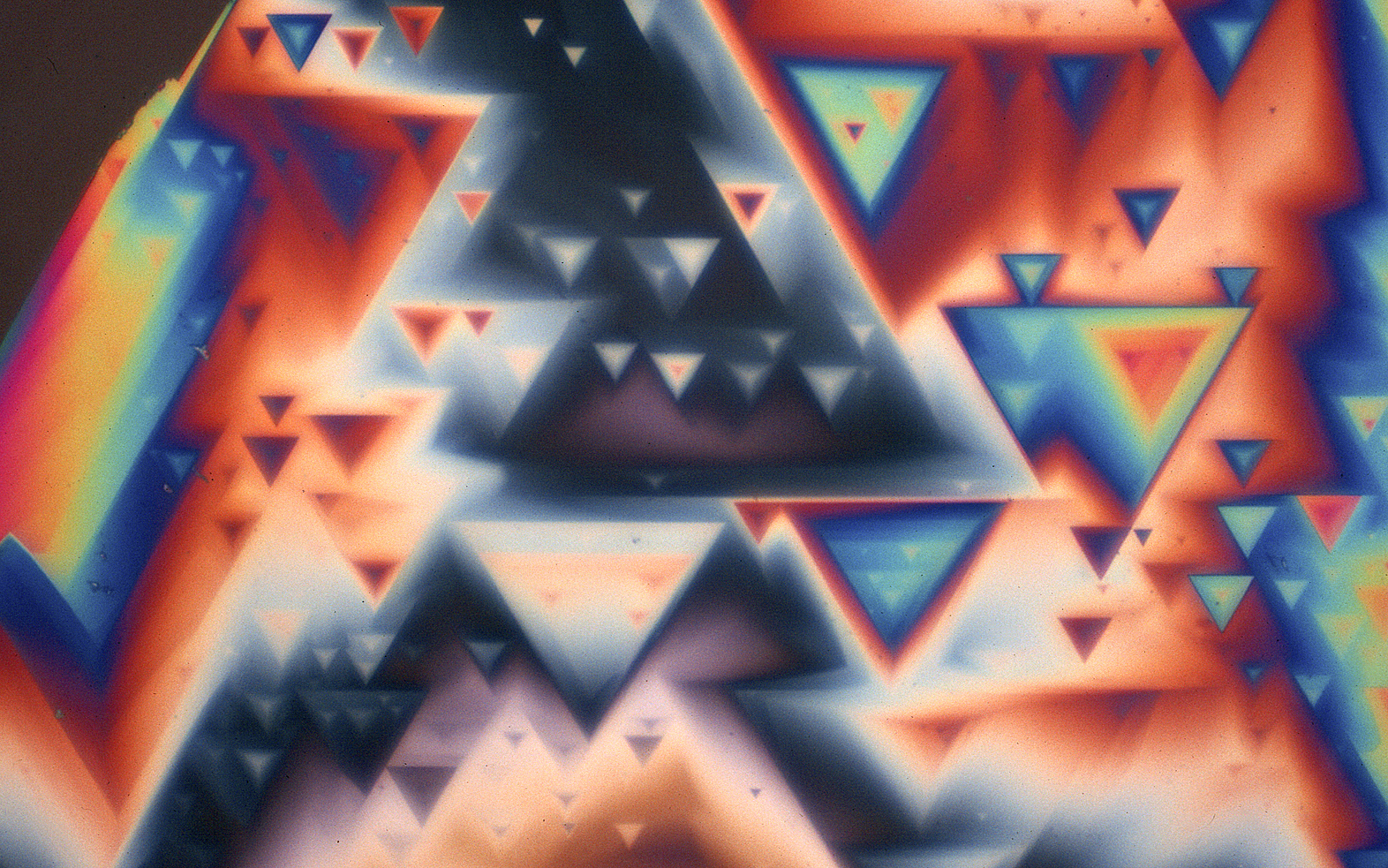

Trigons, Raw Diamond Surface.

Trigons, Raw Diamond Surface.

By DONALD KUSPIT March 28, 2024

Jan Hinsch, born in Hamburg, Germany in 1934, was a master microscopist, an expert on light microscopy, affiliated with Leitz since 1960, when he became an apprentice at its plant in Wetzlar and purchased his first microscope. Since then he has become an expert on microscope optics, the history of microscopy, and lens design, lecturing and working at Leica’s Micro Laboratory in the United States until his death in 2024. He was the Director of the Laboratory for Applied Microscopy. In addition to becoming a master in scientific photography—photography used to render subjects that cannot be seen by the naked eye—Hinsch became a master in fine art photography—photography concerned with the aesthetic character of phenomena, in Hinsch’s case natural phenomena, especially minerals. His photographs are indistinguishably both—miracles of revelation: insightfully scientific and exquisitely aesthetic at once. They bring to mind Einstein’s remark: “After a certain high level of technical skill is achieved, science and art tend to coalesce in aesthetics, plasticity, and form. The greatest scientists are always artists as well.” But to achieve the high level of technical skill necessary to make Hinsch’s insightful photographs—for the microscope offers insight into nature that the eye alone can never have—one must be both a scientist, with knowledge of nature, and artist, with an eye for its innate beauty—its abstract beauty, as distinct from its material beauty.

Kandinsky spoke of his “tendency toward the hidden, the concealed.” He was obsessed with color, distinguishing between its “purely physical effect”—“forgotten when one’s eyes are turned away”—and “psychological effect,” when “its primary, elementary physical power becomes simply the path by which color reaches the soul,” hidden in the body. But there is nothing hidden, concealed about color: it declares itself unequivocally, whatever its effect. Science rather than art has a more serious tendency toward the hidden, as the microscope makes clear, for it reveals what has never been seen before, just as Galileo’s telescope revealed the three largest moons of Jupiter, never seen before the telescope was invented, just as the abstract complexity, not to say idiosyncratic form, of more down to earth materials was never seen before the microscope was invented. Kandinsky sacrificed objectivity on the altar of art, but Hinsch’s microscopic photographs show there is more ingenious abstract art in the objects of nature than any artistic genius can make. When Kandinsky sacrificed nature—Monet’s haystack—on the altar of nonobjectivity he blinded himself to the bizarre abstractions it concealed.

Covellin, Polished Ore.

Covellin, Polished Ore.

The artists in the Renaissance were scientists, as Albrecht Durer and Leonardo da Vinci make clear. Technically brilliant, they dissected nature, describing in detail, with exquisite accuracy, the forms and functions, structure and workings—functional structure—of the nature they carefully observed with the naked eye. It was “different” but not unexpected, on the continuum of everyday perception rather than off—beyond--it, as the unusual, not to say absurd abstractions Hinsch saw through his microscope are. Hinsch sees nature—sees into nature, sees through its everyday appearance—with the aid of a microscope—sees what informs it not simply its form—and a camera, a more sophisticated recording device than a hand with a pencil or paintbrush, however trained to draw or paint with mimetic precision. But the precision of Renaissance mimesis was grounded in an everyday understanding of known reality; Hinsch’s microscope can “see” what is ordinarily unseen, unknown—and unknowable—to the naked eye. Just as Galileo saw what could not be seen without his telescope—the three largest moons of Jupiter—so Hinsch sees what could not be seen without his microscope—the ingeniously, often idiosyncratically abstract structure of minerals, chemicals, snowflakes. It is impossible to see the connection between their appearance to the naked eye—their “normal” everyday appearance--and their “abnormal” abstract appearance to the microscopic eye.

Phloroglucin 1.

Phloroglucin 1.

Abnormal but unexpectedly familiar, as the glorious array of triangles—triangles within triangles, some large, some small, infinitely multiplying, extending into an imaginary depth, appear like mirages in Trigons—polygons with three sides. Large ones seem to spontaneously generate small ones, some blue, some red. All are oddly luminous—abstract light informs the trigons. The photograph is a masterpiece of geometrical abstraction unequaled by any painter’s geometrical abstraction. Covellin, Polished Ore is another exquisitely complex, ingenious geometrical abstraction, composed of subtly curving horizontal bands of rippling blue and brown parts, often oddly luminous and patch-like. Broad sky-blue light informs the bands on the right; those on the left are thin; some are bluish white, some brown. Covellite is a rare copper sulfide mineral in limited abundance. It is prized by mineral collectors. Phloroglucin 1 “depicts” what seems to be a silvery flower growing from a streaking white stone meteor in a blackish blue heaven with an area of yellow light. In sharp contrast Phloroglucin 2 looks like a collapsing glacial field. The blue-tinted ice dissolves into explosive blue water. Apocalyptic blackness haunts the Sturm und Drang scene. Phloroglucinol is an organic compound used in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals and explosives. Hinsch’s work of microscopic art is certainly explosive. What are the three small black amorphous Calder-like forms doing in Hinsch’s more luminous, subtly colorful piece of Crystal? One of the mysteries of artistic nature? Hinsch’s Sulphur seems to be a flourishing plant, dark brown with a pure white core, hardly the bright yellow of elemental sulfur, a crystalline solid. Moon Rock is a magnificently incoherent abstraction made of planar shards of gray and white matter seemingly collaged on a brownish-blackish ground. Petrified Wood is various shades of dark brown with a split on the surface, separating a large, curved form on the left from a striated brown field on the right, with a quasi-organic amorphous “growth” in its lower corner. Hinsch offers us many more ingenious nature-made abstractions, but I would like to end my brief, inadequate description of them by noting his microscopic rendering of six snowflakes, all perfect hexagons, all different, demonstrating nature’s ability to create diversity out of sameness, another indication of its creative genius, impossible to fathom however much we may study and admire it.

Six snow crystals.

Six snow crystals.

I think the best way to understand Hinsch’s abstract masterpieces of nature is by way of Leonardo’s famous remarks in chapter 349 of his Treatise on Painting. “By throwing a sponge impregnated with various colors against a wall, it leaves some spots against it, which may appear like a landscape. It is true also, that a variety of compositions may be seen in such spots, according to the disposition of mind with which they are considered; such as heads of men, various animals, battles, rocky scenes, seas, clouds, woods, and the like. It may be compared to the sound of bells, which may seem to say whatever we choose to imagine”—hallucinate. Hinsch’s microscopic photographs are abstract hallucinations grounded in elemental matter. The marks on Hinsch’s minerals are like Leonardo’s spots. In their cracked and cryptic state the minerals are oracular, fraught with mysterious meaning. I suggest it is peculiarly apocalyptic; the minerals are in a ruined condition. Moon Rock and Petrified Wood explicitly convey death and destruction. All the minerals are dead matter—inorganic. There is an insidious air of despair about them, however enigmatically complex their abstractness. The six snowflakes are the wonderful exception. Each is a perfectly formed but different hexagon. They show that nature can produce miracles of complex clarity and glorious harmony—elated art, however short-lived, for snowflakes melt and disappear, unlike the durable minerals and their abstract surfaces. WM

Donald Kuspit

Donald Kuspit is one of America’s most distinguished art critics. In 1983 he received the prestigious Frank Jewett Mather Award for Distinction in Art Criticism, given by the College Art Association. In 1993 he received an honorary doctorate in fine arts from Davidson College, in 1996 from the San Francisco Art Institute, and in 2007 from the New York Academy of Art. In 1997 the National Association of the Schools of Art and Design presented him with a Citation for Distinguished Service to the Visual Arts. In 1998 he received an honorary doctorate of humane letters from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. In 2000 he delivered the Getty Lectures at the University of Southern California. In 2005 he was the Robertson Fellow at the University of Glasgow. In 2008 he received the Tenth Annual Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Newington-Cropsey Foundation. In 2013 he received the First Annual Award for Excellence in Art Criticism from the Gabarron Foundation. He has received fellowships from the Ford Foundation, Fulbright Commission, National Endowment for the Arts, National Endowment for the Humanities, Guggenheim Foundation, and Asian Cultural Council, among other organizations.

view all articles from this author