Whitehot Magazine

April 2024

"The Best Art In The World"

"The Best Art In The World"

April 2024

White Noise @ James Cohan Gallery

White Noise at James Cohan Gallery

533 West 26th Street

New York NY 10001

June 18th through August 12th, 2009

In the Crosshairs of Art and Sound

White Noise, a group exhibition currently showing at the James Cohan Gallery in Chelsea, explores the complicated intersection of visual art and sound. It does so through almost five decades of art making, across the boundaries of numerous different media, and from a diverse range of domestic and international artists. Analyzing art and sound in the same context is a dauntingly expansive topic—one so large, with so many facets and angles, that it usually suffers from a general lack of direction, a symptom that can be seen in current retrospectives from MOMA and the MET. Like tying to explain in a feature length film how the practices of mass agriculture are slowly poisoning our population, dissecting multiple movements simultaneously is an endlessly fascinating, but possibly ludicrous, goal.

Curator Elyse Goldberg, however, focuses clearly on a material use of sound through art, precariously positioning the exhibition between past precedents and current experimentation. In doing so, she questions our preconceived and limited notions of both of these media, as well as their possible combinations. Offering us select historical artworks to ground the exhibition, she carefully shows the conceptual conflicts of the 1960’s artists who originally united these two disciplines: Robert Morris’ Box with the Sound of its Own Making (1961) illustrates the beginnings of process-based art and the clean aesthetics of minimalism, Robert Smithson’s bizarre collage, Radio Cyclops (1964), garishly speculates on the influences of technology, Joseph Beuys’ pivotal 1969 post-war audiotape Ja, ja, ja, ja, ja, nee, nee, nee, nee, nee [Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes, no, no, no, no, no] contrasts starkly with Yoko Ono’s performative film Fly (1970). The strength of this particular exhibition is its emphasis on how specific contemporary artists have expanded the visual vocabulary of sound. Four of these artists are particularly effective in that they engage us to consider sound while their pieces themselves contain none. Like the predecessors mentioned above, they tackle different aspects of how art can interpret sound, examining what we might “hear” while viewing their silent works.

David Moreno’s sculpture, Quietly Oscillating (2005), is a piece that visually depicts sound traveling. With speakers anchored to the floor and four slinky toys stretched toward the ceiling, the sculpture silently plays an unknown audio track, created by the artist to be outside the range of human hearing. It is not important to know what the soundtrack is, so long as we can see it. Viewing his sculpture is seeing the invisible; sound gently moves and vibrates the spiral toys like an oscillating fan, as it pushes toward an unknown recipient. Moreno directs attention to our ability to hear sound by allowing us to see his visual representation of it. His sculpture acts as a descriptive diagram of the process of human hearing.

Tacita Dean, in her piece Magnetic Aviary: Crows, Raptors, Fowl, Game, Water Birds, Ornamental, Vulture, Garden, Seabirds (1996, 1998) presents viewers with grouped lists of birdcalls, arranged and framed as a set of serial drawings. Delicately written bird names, spaced to resemble lines of poetry or song lyrics, and grouped and framed by species, lend a single written word the unique power of an individual birdcall. Each bird name, a gull. . . a partridge. . . a vulture, appears to be set within, perhaps even literally on, the magnetic tape of its own soundtrack, visually reflecting the duration of a particular birdcall. Seeing the voice of a bird on paper evokes the possibility of hearing sounds for a multitude of other words. Altogether the piece can be read as a cacophony of birds calling all at once; within the individual frames it is the song certain species sing together, and line by line it sounds like the song of an individual bird we recall from memory. Magnetic Aviary is a powerful piece that silently turns our natural environment into remembered and half imagined sounds.

Robin Rhode’s black and white, silent film, Untitled (Microphone) (2005), is a ten minute sequence consisting of a single performer interacting with a blank white wall. Rhode’s filmed performer creates a chaotic gesture drawing on the wall while enacting the familiar movements that singers and rappers mime while onstage. As the film progresses, a layered image depicting numerous different microphones, cords, and stands, all smudged with motion, appears slowly on the wall—the singer’s exaggerated performance creates the drawing we view. Though the film shows the process of a drawing being made, we are also watching, not hearing, a song being sung and a dance performed. It is difficult to discern whether the performer is engaging a two dimensional microphone in a childish attempt to bring it to life, or if each movement and gesture adds another stroke to the drawing. Both appear to happen simultaneously. Microphone tackles the complicated relationship between a performer and his audience. Seeing the singer almost from behind, the white wall existing where an audience should be, we become implicated in the spectacle. Instead of feeling like an audience, we are situated onstage. The film lets us question the impulse to perform and our role as spectators.

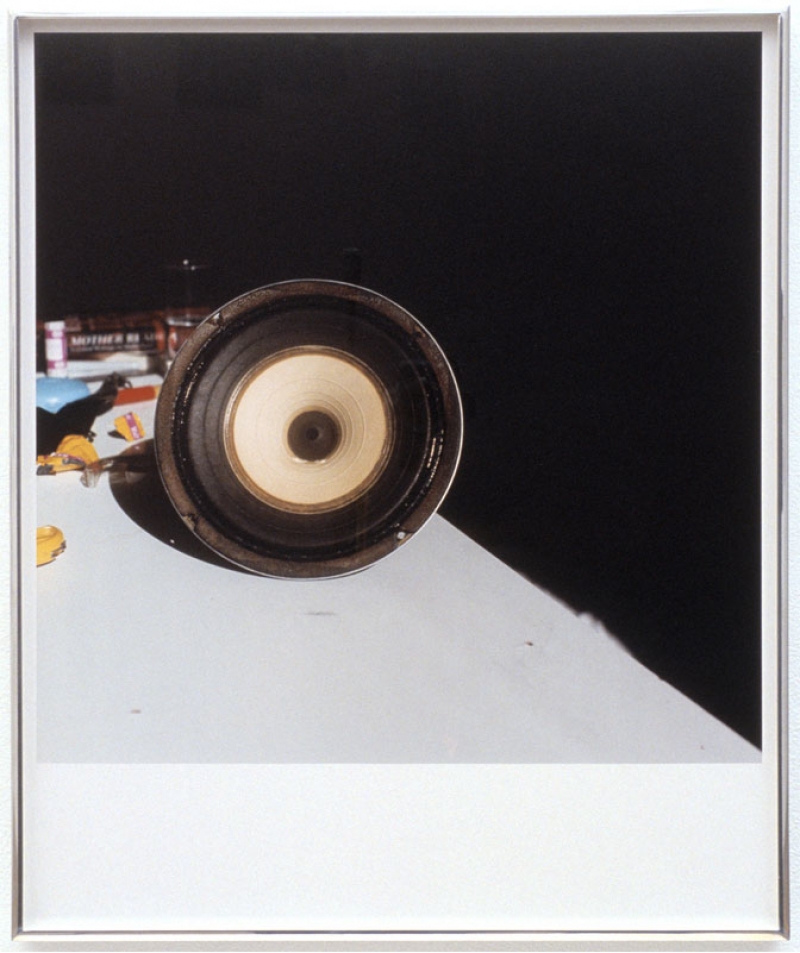

Morya Davey, in a set of four color photographs, documents equipment through which sound seeps into our everyday lives—sound playing from records, coming out of stereos or through the radio. Her images depict cluttered and dusty interior spaces, apartments that seem to exist somewhere between total abandonment and beloved filth. Her images are not, however, portraits of musical devices. Instead, they serve as narratives for the cultural impact that sound and music can have, on both our quotidian lives and our most fantastical imaginings. Her photograph, Untitled (Nyro) 2003, showing a stack of records romantically lit by afternoon sun, reminds us of our cherished musical celebrities. Another photograph, Untitled (Receiver) 2003, of an old stereo with a new radio stacked above, washed dishes framed in the images foreground, recalls morning radio alarms and talk show hosts. The objects living in Davey’s interiors, spaces full of dirty records, dated icons, and outdated brands, give a voice to the timeless, the forgotten, and the obsolete.

The crosshairs between disciplines, though highly problematic from a standpoint of categorization, are always beneficial for the disciplines themselves. The junctions between visual art and other media are full of possible exploration, as it is through these crossovers that our notions of categories are blurred. White Noise showcases an array of conversations discussing art, sound, and music, and gives us a chance to listen to art. Instead of emphasizing artifacts that pay homage to past genres, White Noise pushes us to listen to those contemporary artists who have adopted art and sound, making the combination their own. It is interesting to speculate about how vast the overlap between art and sound can be, and what new routes artists like these four might discover in order to continually reinvent sound visually through art.

Alissa Guzman

Alissa Guzman is a culture critic living and working in New York City.